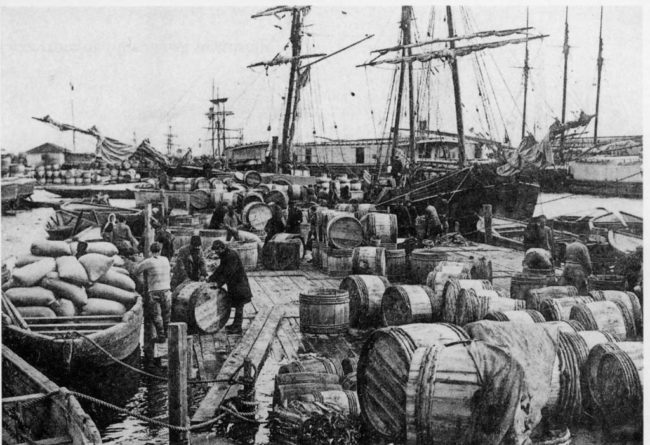

The long history of ties between Russia and Norway dates back to the Middle Ages, when trade started to flourish. In the 17th and 18th centuries, a pidgin language known as Russenorsk (or Moja på tvoja), which coast dwellers and Norwegian traders of grains and fish used to understand each other, emerged.

Norwegian fishermen Photo: Lofoten Stockfish Museum

Port of Arkhangelsk Photo: romanovempire.org

Russenorsk continued to be spoken into the early 20th century, but fell out of use when free movement was banned in these places. Even with a closed border, the Russian-Norwegian Arctic continued to be a territory of close ties and shared problems related to peaceful co-existence in a harsh northern environment.

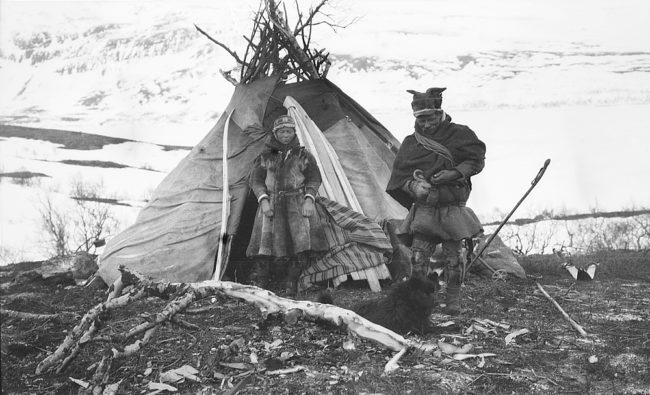

The specific ties in the region of the Barents Sea are reflected in corresponding terms: “Barents Region,” “Barents cooperation,” “Barents summit,” and others. The Kirkenes Declaration of Cooperation in the Barents Euro-Arctic Region was signed in 1993, after the fall of the iron curtain. Twenty years later, in 2013, the leaders of the Barents countries (Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Finland, and Sweden) participated in the Barents Summit in Kirkenes and signed a new agreement that recognized the importance of cross-border contacts between indigenous peoples and the development of cooperation between young people and regional institutions like the Barents Euro-Arctic Council, the Barents Parliamentary Conference, the Barents Regional Council, and the Barents Indigenous Peoples Congress.

The updated Kirkenes Declaration of 2013 states that: “Urgent issues on the European agenda, such a strengthening tolerance and combating radicalism, xenophobia and violent extremism, related to discrimination, social exclusion and negative stereotyping of minorities. In order to solve these problems, we need to use wide-ranging efforts in such areas as legislation, education, social dialogue and awareness-raising. Although responsibility for combating hate crime and intolerance primarily lies with the state authorities, civil society can play a crucial role in this endeavour.”

However, it was with “awareness-raising” and overcoming the “negative stereotyping of minorities” that problems start to emerge.

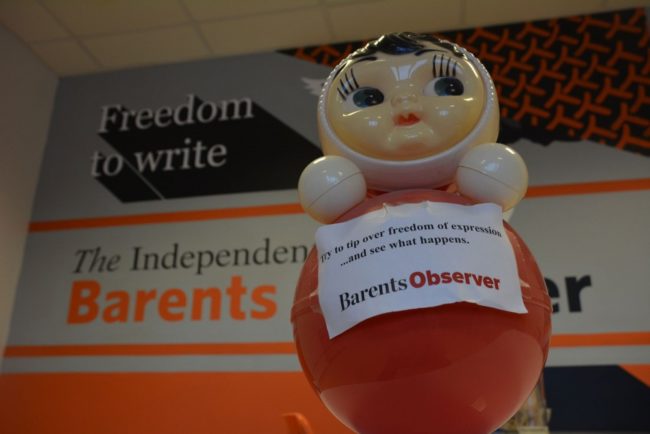

This year, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor) blocked the Kirkenes publication Barents Observer, which has written about the region’s problems in Russian and Norwegian since 2002. The cause for the blocking of the entire site in Russia was the publication of an article about Dan Eriksson, a gay Saami from northern Sweden who went through a painful struggle for self-acceptance and now helps gay Swedes cope with psychological problems and suicidal thoughts. The idea of the article was clearly life-affirming—it begins with the words “Life can be hell. But it can be different when people have the chance to speak about painful things and develop the courage to be themselves. Today, after many years of psychological problems and two suicide attempts, Saami Dan Eriksson takes joy in life and is proud of his homosexuality.”

This article recounts how it took Dan Eriksson a long time to accept himself, how he suffered from a double stigma, and how difficult it was for him to stop feeling ashamed of his heritage and orientation. Now he can say: “Today I am proud to be a Saami. I am proud to be a gay Saami.”

Dan Eriksson found the strength within himself to come to grips with what he calls “social phobia,” which is the constant fear of being viewed in a negative light by the people and prejudices surrounding you. He also understands the problems of people from traditional societies, where standard gender roles and stereotypes are particularly strong: “As a member of the Saami people, you feel enormous pressure to be strong and handle everything on your own. But there’s nothing wrong with showing that sometimes you can be weak.” His victory over his fear and pain, which became possible with support from his ex-wife and her mother, gave Dan the strength not just to live on, but also to help others through the organization Suicide Zero. His approach is as follows: “It’s unbelievably important. We have to speak, we have to listen. We don’t have to understand, but we do have to listen. And we shouldn’t be afraid to ask from time to time if someone has thoughts of suicide. It’s hard, but it’s dangerous not to speak about this.”

It is clear that the story of this person’s positive experience can in no way violate the ban on “calls to suicide.” Be that as it may, in its decision no. 67131 of January 23, 2019, the Federal Service for the Oversight of Consumer Protection and Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor) notified Roskomnadzor of the presence of banned information about ways to commit suicide on a website page. Roskomnadzor demanded that The Barents Observer delete its article about Dan Eriksson, but editor-in-chief Thomas Nilsen categorically refused and interpreted the media regulator’s action as an encroachment on freedom of speech. After this, “in connection with the website owner’s failure to take measures to remove this information and the hosting provider’s failure to adopt measures to restrict access to this article, under Decision No 236707-IP-on of Roskomnadzor, the network address enabling identification of this website on the internet was entered into the Unified Register” (that is, was blocked).

ADC Memorial supported The Barents Observer’s claim against Rospotrebnadzor and Roskomnadzor requesting that the blocking be reversed. Representatives for the publication complained to the court that its rights had been violated in Russia and showed that the article did not contain anything illegal. They also presented the opinion of a professional psychologist, who confirmed that the article did not contain any calls to suicide or specific descriptions of ways to commit suicide.

The article’s reference to Dan’s attempted suicide as he tried to come to terms with his sexuality (even though he was able to ask a close person for help before it was too late and was saved) can hardly be termed “a description of a means”—otherwise, we will have to ban such classics as Chernyshevsky’s What is to be Done, which describes Vera Pavlovna’s thoughts in a difficult hour, not to mention Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina.

The proud gay Saami’s idea that tragedies are often the result of suppressing the problem and refusing to discuss the risk of suicide was left unanswered by Moscow’s Tverskoy District Court. Dan’s simple and humane words—“According to statistics, 1,500 suicides occur in Sweden every year. That’s four per day, much more than the number of traffic fatalities. We have to talk about suicide, we have to find the courage within ourselves, and we have to listen”—received only a dry and lifeless response in the court’s decision: “Upon review of this case, the court could not establish the totality of these circumstances; the allegations of The Independent Barents Observer AS concerning illegal actions (inactions) could not be confirmed.”

The ruling of the Tverskoy District Court is being appealed with the Moscow City Court. And The Barents Observer continues to write about important events for the region, including in Russian, even though it is blocked in Russia. For example, in late October it is a tradition for this outlet and other media outlets in Norway and Russia to report on the liberation of eastern Finnmark (the northern part of Norway bordering Russia) from the German fascists by the Soviet Army; 2019 marked the 75th anniversary of this event.

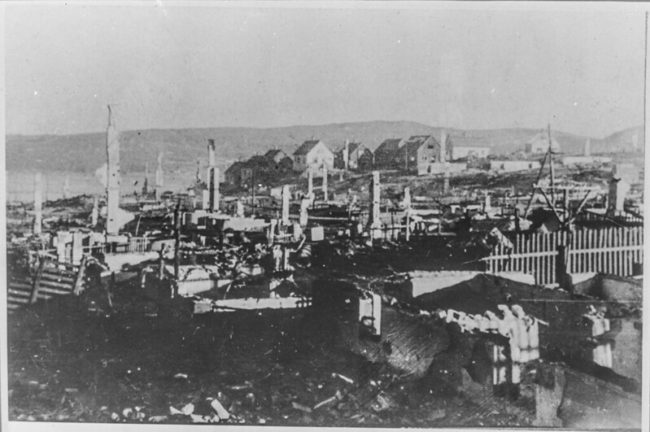

Unlike the residents of many other countries that the Soviet Army entered during World War II, the Norwegians of Finnmark remain grateful to Soviet soldiers for their liberation and for helping to restore razed buildings, bridges, and roads (the Germans followed the scorched earth policy during their retreat) and provide supplies during a terrible famine.

Kirkenes. Photo: TASS photo report. National Archives of Norway

Scene from the film “Under a Stone Sky,” 1974

The fond memories of the Soviet presence in Finnmark are connected with the fact that the representative of Soviet headquarters in Kirkenes was the renowned Orientalist Igor Mikhailovich Diakonoff (1915–1999), who spoke Norwegian. He is still remembered in Norway and became an honorary citizen of Kirkenes after the war. During a polar night of 1944, Diakonoff wrote his philosophical tract “Kirkenes Ethics,” which was inspired by his tragic personal and simultaneously historical experiences, including Stalin’s repressions (his father perished) and what he saw in the war. “Naturally, war stands in the way of a universal understanding of the concept of ‘my neighbor’ and in any case is the greatest of crimes. But for now let us leave it aside and avoid asking who is guilty of this war. Let us treat those ethical problems that affect simple people, like ‘we’ and ‘you’ during war. War immediately divides all the people by a definite frontline. No ethical advantages belong to the enemy. To kill the enemy does not mean to commit homicide. In theory it relates only to an armed enemy wearing a military uniform, who is not a prisoner of war. In reality none of this is true. A pilot of a bomber, when he drops his death-dealing bombs, certainly knows that he will or may tear to pieces along with an armed enemy also civilians and children. An artillery-gunner possesses the same knowledge as an infantry man (more frequently than usually assumed). Robbery, theft, and rape accompany every war. The author of the “Kirkenes ethics” started his military service with the theft of hay from a peasant: his people were accommodated in a shack with no heating. This was in October, and the place was not far from the Arctic Circle.”

The idea that war is a crime appears banal, but in the context of contemporary Russian history, it is worth recalling these lines written by a witness to World War II. This year’s ceremonial events in Kirkenes were criticized by The Barents Observer specifically for their excessive militarization, particularly the invitation of members of the Young Army Cadets National Movement from Russia (at approximately the same time, the Russian Ministry of Education recommended holding competitions in Russian schools for stripping and assembling Kalashnikovs in honor of the birth of the weapon’s inventor). However, The Barents Observer cannot be accused of one-sidedness: It gave the coordinator for the Norwegian side an opportunity to express his objections.

Ruins of Kirkenes, 1944. National Archives of Norway

Ruins of Kirkenes, 1944. National Archives of Norway

Diakonoff writes: “The Norwegians gave us a wonderful reception. No hugs or kisses, of course, that’s not their custom. But still, they treated us very well…. We also treated them well. We ate general’s rusk at headquarters, but the units had their own field kitchens and baked bread. The Norwegians had no supplies at all, their entire production was destroyed by the Germans, and we didn’t have the power to set things right. In particular, it was not within our power to pull off all the good deeds described in the official history of the Karelian Front. The units helped with food and even gave some extra food to the children, and later headquarters provided another important form of assistance to the population… The problem of finding accommodations for people—both our people and the Norwegians—was extremely complex. The municipality moved as many people as it could into the remaining homes, but there were very, very few of them. Many people lived in snow-covered improvised shelters in the woods. Bjørnevatn and Neiden were intact, but almost nothing was left of the outskirts or Kirkenes. The buildings that were still standing held our soldiers and officers. In early November, our command—I don’t know who exactly, but I think General V.I. Shcherbakov—published an order requiring all our soldiers to leave these homes. The Norwegians were also transferred a large number of the remaining German barracks. There was some moaning and groaning about the order to leave these houses, and I had to help with this from time to time. The Museum of the Soviet Army in Moscow has a page torn out of a notebook that reads: ‘The bearer of this, Citizen Vilhelmsen V., is being moved into this house by the local government. At the order of the commandant for the city, please clean the premises. November 2, 1944. Duty Commandant Senior Lieutenant I. Diakonoff.’ ‘Duty commandant’—that was something I came up with: I had no position, I was ‘forsaken.’”

One has to agree with the Norwegian journalists: It would be better to see less of a military outlook in the Arctic (and in other places as well). On October 25, the ensemble of the Northern Fleet and the Norwegian military orchestra from Harstad performed on the stage of the unique concert hall Fjellhallen, located on a cliff in Kirkenes. As Aleksey Yankovsky-Diakonoff, who gave a lecture about his father in Kirkenes during the celebration, wrote: “the idea that if you’re going to meet the military, then it should be on stage, is a good idea.” We would add, especially now, when the media is publishing alarming reports about a growing Russian military presence in this area (the strange “green men” in Svalbard and the largest Russian submarines exercises in the Arctic, which were reported by Norwegian sources). More importantly, freedom of speech and the press in this region is, in the broadest sense, awareness. Barents cooperation in the Barents region should be peaceful and open, and The Barents Observer should be independent and free from censorship.

Olga Abramenko,

expert of the Anti-Discrimination Center «Memorial»

Feedback

Feedback