The annexation of Crimea in 2014 marked the beginning of merciless repressions against the inhabitants of the peninsula who disagreed with the new government, primarily the Crimean Tatars. Criminal cases, kidnappings, tortures, and long prison terms have become a grim reality. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, terror in Crimea intensified and spread to new territories occupied by Russia.

Already in March 2014, almost immediately after the annexation of Crimea, human rights activists began to document numerous cases of abductions, arbitrary detentions, forced disappearances, tortures, and extrajudicial executions of representatives of the Crimean Tatar people. Criminal cases were initiated against most of the detainees, mainly on the counts of membership in “Hizb ut-Tahrir”, which is recognised as a terrorist organisation and banned in Russia. Less often investigations were opened on the charge of alleged participation in the activities of the Chelebidzhikhan volunteer battalion. There are known cases of reprisals against relatives and neighbors of the accused. Later, the participants of “Crimean solidarity” (the association of activists and relatives of accused and already convicted Crimean Tatars) faced persecution.

At the same time, the new government of Crimea quickly began to take repressive measures against the distinctive culture and identity of the Crimean Tatars. In particular, all public organizations, mass media and religious associations were obliged to re-register themselves, and a number of them, including the Crimean Tatar ones, failed to re-register. The Crimean Tatar media were closed or turned into an instrument of Russian propaganda. The Crimean Tatar language was pushed out of the education system and the public sphere. The Mezhlis, the highest representative body of the Crimean Tatar people, was declared “extremist” and banned, and its leaders were forced to leave Crimea. Instead of it, the Russian authorities created controlled bodies, such as the “National-cultural autonomy of the Crimean Tatars.”

Due to the incessant persecution, hundreds of Crimean Tatars were forced to leave Crimea. In relation to those who remained but did not want to subscribe to the concept of “Russian Crimea”, the repressions continued. In 2016, the PACE in its Resolution stated that the cumulative effect of the repressive measures of the Russian authorities against the Crimean Tatars since the annexation was a threat to the very existence of this community as a separate ethnic, cultural and religious group.

Intensification of repressions since the beginning of the war

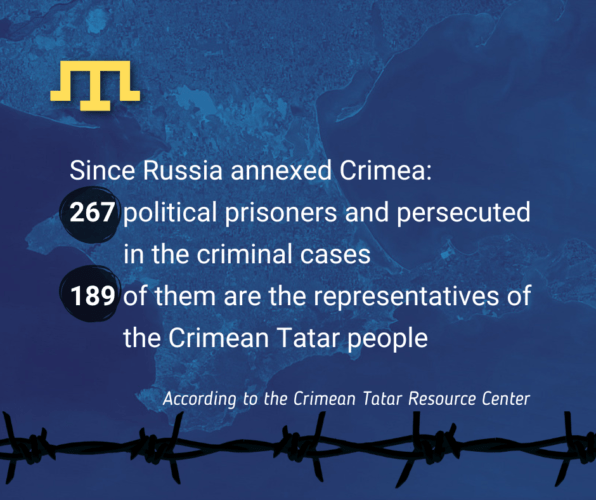

The full-scale war unleashed by Russia against Ukraine on February 24, 2022, opened a new phase of repression against the Crimean Tatars. Almost immediately after it began, a law was passed in the Russian Federation that provides for up to 15 years in prison for disseminating false information about the actions of the Russian military, which made dissent in Crimea even more dangerous. According to the Crimean Tatar Resource Center (CTRC), between February and September 2022 alone, Russian security forces conducted 25 searches, 108 detentions, and 124 interrogations, interviews, or “conversations” in Crimea. For 9 months of 2022, 138 people were arrested in Crimea, 104 of which are Crimean Tatars who oppose Russian occupation and military aggression. Employees of the CTRC note that most of the other violations by the security forces affect representatives of the Crimean Tatar people and that this practice has become systematic in Crimea.

With the beginning of the active phase of the war and the occupation of Kherson, where many Crimean Tatar settlements are located, the persecution of the Crimean Tatars began outside Crimea. So, on June 22-24, raids were carried out in the houses of Crimean Tatars in the Genichesk district of the Kharkiv region, with their subsequent detention. Bus driver Rasim Asanov, cultural worker, choreographer Susanna Ismailova, and IT specialist Ruslan Ismailov were taken by the Russian military to the basement of school No. 17 of Genichesk and accused of supporting the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people. The brothers Edem and Refat Karamazov disappeared without a trace. On June 28, after a house search, Crimean Tatar Rustem Seitmemetov disappeared. Later it became known that he had been in the basement of vocational school No. 17 of Genichesk for a long time, after which he was transferred to one of the pre-trial detention centers in Kherson. He was accused of preparing sabotage. On July 23, Appaz Kurtamet, a 20-year-old Crimean Tatar, teacher of the Crimean Tatar language from Novoalekseevka, was detained at the Chongar checkpoint. He was trying to go to Crimea to live with his mother. Later, he was found in SIZO-1 in Simferopol, where he ended up on charges of transferring money, allegedly to finance the Islamic battalion “Crimea”.

Until October 25, 2022, SIZO-1 was the only pre-trial detention center in Crimea. It was built over 200 years ago and is designed for 747 people. As prisoners and human rights activists reported, the cells in the pre-trial detention center were at times overcrowded more than twofold, so the arrested had to sleep in turns. Due to the lack of space, the detained Crimean Tatars and others persecuted for political reasons were placed in pre-trial detention centers in neighboring regions – Krasnodar Krai or Rostov Oblast. On October 25, a new pre-trial detention center for 366 people was opened on the territory of IK-1 in Simferopol. According to KrymSOS, about 60-70 people were transferred there, mostly those detained in the newly occupied territories of southern Ukraine. There is still no official information about this pre-trial detention center on the website of the Federal Penitentiary Service of the Russian Federation and the Federal Penitentiary Service of Crimea.

In 2022, the persecution of Crimean Tatars intensified for participation in the “Crimean Tatar Volunteer Battalion named after Noman Chelebidzhikhan”, a military formation recognized in the Russian Federation as a banned terrorist organization. Belonging to the battalion is often attributed by the Russian investigating authorities to those who participated in the actions of the civil blockade of Crimea in September-October 2015. Many detainees complained of torture and other gross violations in order to obtain confessions, so there is good reason to believe that the majority of those detained and convicted for participation in the activities of the battalion are innocent. Currently, according to human rights activists, the number of Crimean Tatars who ended up in the Simferopol pre-trial detention center on this charge can reach 10 people. Since the beginning of the war, many detainees have already received harsh sentences: from 5 to 8.5 years in prison.

On September 21, 2022, the defendants in the case of blowing up a gas pipeline in the village of Perevalnoye (August 23, 2021) received huge sentences. Nariman Dzhelal, leader of the Crimean Tatar national movement, vice-chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, was sentenced to 17 years in a maximum security labour camp with a fine of 700 thousand rubles and restriction of freedom for a period of 1.5 years. Brothers Aziz and Asan Akhmetov were sentenced to 15 years in a maximum security labour camp and fined 500,000 rubles each.

After the annexation, Nariman Dzhelal continued to live in Crimea, engaging exclusively in civilian activities in the interests of the Crimean Tatars, not associated with any acts of violence. Amnesty International said in a statement:

“The sole purpose of the criminal prosecution of Dzhelal is to silence him and stop his independent civic activities.”

During the trial, it became known that the witnesses, who pointed to the involvement of the accused in the case, gave their testimony under torture. The searches of the suspects, according to the lawyers, were carried out with multiple violations: without giving the accused copies of the decisions, without drawing up detention protocols, in violation of the right to contact a lawyer. The charges against Dzhelal were based on the testimony of three hidden witnesses and files found on his mobile phone. The Akhmetovs also alleged numerous violations by the investigation, threats and torture. In particular, Aziz Akhmetov claimed that the security forces beat his brother, Asan, took him to the forest, threatened him with execution and tortured him with electric shocks in order to force him to confess. Aziz himself, according to him, spent almost a day after his arrest with a bag on his head in a cell in the FSB building. All this time he did not sleep, could not move freely and leave the building, he was not allowed to drink and eat. The Akhmetovs’ lawyer, Nikolay Polozov, who is in charge of the cases, also stated that the brothers were tortured with electric current by connecting electrodes to their heads.

Repressions against human rights activists and lawyers in Crimea also intensified. On May 26, 2022, in Simferopol, employees of the Department for Countering Extremism detained a lawyer Edem Semedlyaev. The reason was a tag on Semedlyaev’s Facebook account in a post by another user of the social network, allegedly discrediting the Russian army. On the same day, the lawyer was found guilty and fined 75,000 rubles.

After the trial of Semedlyaev, his lawyer Nazim Sheikhmambetov was detained right outside the court building. According to the protocol, the reason for his detention was his violation of public order on the night of October 25-26, 2021, when several Crimean Tatars gathered near the Central District Police Station in support of the detained activists. On May 27, 2022, the Central District Court of Simferopol sentenced Sheikhmambetov to eight days of administrative arrest.

On the same day, two more lawyers who were supposed to defend Sheikhmambetov in court, Emine Avamileva and Ayder Azamatov, were detained. They, like the defendant, were accused of organizing a massive simultaneous gathering of citizens in public places, which led to a violation of public order on October 25, 2021. Later, Emine Avamileva was arrested for 5 days, and Ayder Azamatov for 8 days.

Immediately after the arrests, the head of the Crimean Human Rights Group, Olga Skripnik, stated that such detentions were aimed at intimidating all Crimean lawyers defending human rights on the peninsula:

“This is a full-blown policy of intimidation, including lawyers. This is a signal not only to these four lawyers, but it is also a signal to the entire legal community, which so far remains independent and tries to work exactly as lawyers and protect the interests of its clients. [A signal] that they are watching you, that they will always fabricate something on you, that “you are under their hood”. And the administrative arrest against lawyers is a very blatant step, with a certain implication of imprisonment, [like if they were saying:] ‘we are ready to go further and shut you down altogether.’”

On July 15, 2022, three lawyers: Lilya Hemedzhi, Rustem Kyamilev and Nazim Sheikhmambetov were deprived of their status and the opportunity to practice law, and on August 11, during numerous searches in the homes of Crimean Muslims, at least 9 lawyers faced targeted blocking of their mobile phones.

The mass mobilization of Crimean Tatars in the occupied territories into the Russian army

One of the elements of the repressive policy against the Crimean Tatars can be considered the “partial mobilization”, which is carried out as part of Russia’s military aggression in the territory of Ukraine. The representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Tamila Tasheva, said that during the first days of mobilization, the Crimean Tatars received about 1.5 thousand draft notices.

The mass conscription provoked a wave of departure of the Crimean Tatars from the peninsula. Those who leave Crimea, and there are thousands of them, according to Suspilne, call their departure “self-deportation.” Many leave for the countries of Central Asia, where in 1944 their relatives were deported by the Soviet authorities and where many still have relatives or acquaintances. For some of them, the validity of the Ukrainian foreign passport, issued before 2014, has long expired. Others, mostly young people, have never had such a document. Those who were able to leave are trying to restore or issue Ukrainian passports in the Ukrainian embassies of the countries that accepted them in order to be able to travel to Europe and not return to the territory occupied by Russia.

Mobilization in Crimea, on the occupied territory, grossly violates the Fourth Geneva Convention and is considered a war crime by international law. Especially cynical is the mobilisation of the Crimean Tatars, who from the very beginning of the Russian aggression opposed the occupation: now they are being forced into a war against their country, their relatives and their countrymen.

Discrediting of the Crimean Tatars in the Russian media

During the occupation of Crimea, the narrative about Crimean Tatars as “terrorists”, “extremists” and “agents of foreign special services” began to spread in the public space through the Russian state media and politicians. Again, as in Soviet times, politicians and journalists began to speculate on historical myths about the Crimean Tatars as “collaborators and traitors to the Soviet people” during the Second World War; such theses as “Crimean Tatars are not an independent people”, “Crimean Tatars need to be evicted again”, “Crimean Tatars are not respectable, they must be avoided” are widely circulating. Officials of various levels have made such statements more than once, which resulted in growing Tatar-phobic sentiments in Crimea and their popularisation within Russian society.

Against the backdrop of discriminatory and offensive rhetoric, which is openly broadcasted by Russian politicians and Russian media outlets, cases of harassment and other discriminatory practices of Crimean Tatars by both ordinary people and civil servants have become more frequent in Crimea. According to the testimonies of the Crimean Tatars living in Crimea, after the annexation, their close friends, neighbors, colleagues and clients began to treat them worse. Thus, one of the representatives of the Crimean Tatar community we interviewed in 2017 said that immediately after the so-called referendum, the neighbors – ethnic Russians – simply stopped communicating with him:

“Neighbors, Russians, communicated [with us] until March 14, and then they put up a fence and without disputes, without anything, simply stopped communicating. It is clear that the neighbors went to the referendum, and the Crimean Tatars, it is understood, were for Ukraine.”

Here is how one Crimean Tatar describes his experience with the healthcare system:

“90% of people living in our village are Crimean Tatars. An ambulance comes to us very rarely, when it is a matter of life or death. In August 2015, a man was electrocuted, and the ambulance came in 3 hours and 23 minutes, it was too late. And it takes only 15 minutes to drive to us from the hospital. I asked my friends who worked in the hospital why did this happen. They said that there were 6 free cars in the parking lot.

In the hospital, I often noticed that I had to sit for a very long time. They took my card, my last name and first name are visible there, [and after that] I could wait for 2-3 hours. Once [in August 2014] I came to the district clinic with an acute injury for 3 days in a row, I had an ankle fracture. The nurse did not love me because of my nationality even before, under Ukrainian rule. When I got to the appointment, they told me that I just had a fracture, but I had a displacement – they did not work efficiently. Several times the nurse spoke openly to the entire hospital: ‘You must leave here, you must be deported.’ In 2009-2010, this attitude was hidden, they did not always show it, but at the moment they have a free hand.”

Statements that defame Crimean Tatars are made by high-level Russian officials and broadcasted by Russian state media. Among them, for example, is the statement by the Secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation Nikolay Patrushev (July 9, 2018) that the political, social and economic situation in Crimea remains unstable due to the government of Ukraine, Ukrainian nationalists and the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people. During the investigation into the case of the gas pipeline explosion in the village of Perevalnoye, the head of Crimea appointed by the Kremlin, Sergey Aksyonov, named (September 15, 2021) the leader of the Mejlis, Nariman Dzhelal, as an agent of the US intelligence services, although his guilt in the incident was not proven, and the connection with foreign intelligence services was not even considered by the investigation.

Violation of linguistic and cultural rights of the Crimean Tatars

The discrediting of the Crimean Tatars also finds its way into the school curriculums. In 2019, the Ministry of Education made an attempt to introduce a new textbook on the history of Crimea for the 10th graders in Crimean schools. The textbook contained statements that during the Second World War the Crimean Tatars more than other ethnic groups in Crimea welcomed the Nazi army and more than other ethnic groups collaborated with the occupation administration. Under pressure from the Crimean Tatar community, textbooks were withdrawn from schools for examination.

Learning and teaching the Crimean Tatar language is increasingly problematic. In 2021, 218,974 children studied in Crimea, of which 212,090 students studied in Russian, and only 6.7 thousand children studied in Crimean Tatar, despite the fact that according to the Russian census of 2014, there are 232,340 Crimean Tatars in Crimea. According to our data, in most schools, Crimean Tatar lessons are only optional, often at late hours or on weekends. At the same time, school administrations often refuse to open new elective courses in the Crimean Tatar language. For example, in March 2019, at secondary school No. 8 in Simferopol, the school administration asked the parents of Crimean Tatars to refuse to study their native language. In June 2018, in the village of Tsvetochnoye, Belogorsk district, the principal of a school refused to accept applications from parents to study the Crimean Tatar language. In August 2018, the director of school No. 46 in the village of Orlovka in the Nakhimovsky district (Sevastopol) refused to open a class with the Crimean Tatar language of instruction. All these situations were resolved only after the intervention of human rights activists, lawyers and with the active participation of the parents.

In 2017, the Russian-controlled Crimean authorities adopted a local bill “On the state languages of the Republic of Crimea and other languages of the Republic of Crimea”, which provides for the possibility of obtaining secondary (not higher) education in any of the three state languages, but language training is organized by an educational institution depending on opportunities of the education system. It would seem that the adoption of this law should have approved the equality of languages both in the educational and the public sphere. However, now, based on this provision of the law, educational institutions can refuse to study the language due to a lack of resources or opportunities, and school administrations are already using this argument to refuse to study the Crimean Tatar language.

Crimean Tatar national symbols, images and heritage of historical figures, attributes of the Crimean Tatar identity are used in the development of the pro-Russian propaganda discourse. At the same time, the authorities demonstrate a disdainful attitude towards the Crimean Tatar cultural heritage and memorable places. For example, they want to create a recreation area in Bakhchisaray on the territory of the ancient Muslim cemetery Sauskan, despite the protests.

Other Crimean Tatar shrines are also desecrated and destroyed – these are monuments and tombstones in cemeteries, memorial plaques dedicated to the Crimean Tatars who died in World War II, or the ones that have Crimean Tatar symbols on them. In just six years after the annexation, 23 such cases were recorded in Crimea – a little less than in 20 years before the annexation of Crimea. As a rule, acts of vandalism become more frequent on the eve of memorable dates associated with the deportation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944. Fixing the destruction and damage of cultural monuments, the activists are trying in vain to get a reaction from law enforcement agencies.