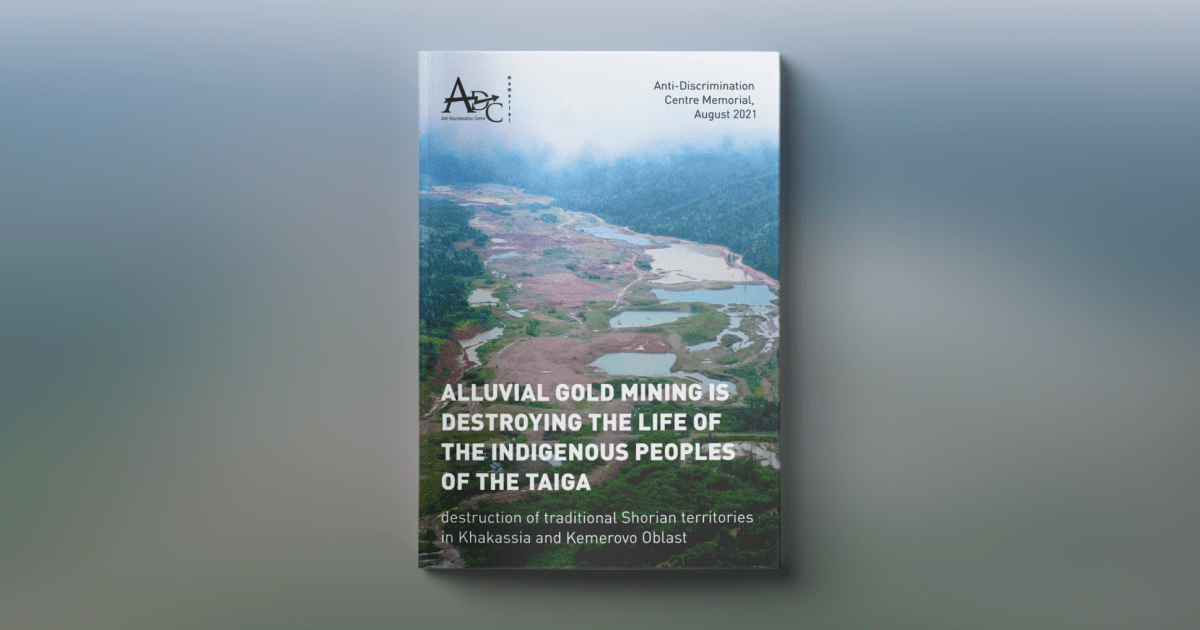

This report describes the catastrophic consequences of gold mining and violations of the rights of the Shor – a small Indigenous people living in the southwestern area of the Republic of Khakassia and in southern Kemerovo Oblast. Placer gold mining destroys rivers and the natural environment in general in places where the Shor people traditionally reside, which poses a threat to their existence as a people and to their traditional language and culture, particularly because it is their centuries-old relationship with the nature surrounding them that determines their worldview, daily activities, and way of life.

The Shor are a Turkic-speaking small Indigenous people living in southern Kemerovo Oblast and in neighboring districts of the Republic of Khakassia, the Altai Republic, and Krasnoyarsk and Altai krais. Their population reaches almost 13,000, and 24 percent of them live in cities (2010 census).

This report is based on field data collected by ADC Memorial in June 2021 and open source materials. ADC Memorial would like to express its gratitude to the members of the Indigenous peoples and local communities of Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast and the experts, activists and environmentalists who provided information for this report.

Preface

This report describes the catastrophic consequences of gold mining and violations of the rights of the Shor – a small Indigenous people living in the southwestern area of the Republic of Khakassia and in southern Kemerovo Oblast. Intensive commercial exploitation – primarily open-pit coal mining and gold mining – of ancestral lands poses a threat to the Shor’s existence as a people and to their traditional language and culture, particularly because it is their centuries-old relationship with the nature surrounding them that determines their worldview, daily activities, and way of life. According to the 2010 census, there are almost 13,000 Shor in Russia, and their numbers have dropped by 14 percent since the mid-20th century. 1Russian law classifies peoples who live on ancestral lands; have preserved traditional lifestyles, economic activities, and trade; have a population in Russia of under 50,000 people; and who identify as an independent ethnic community as small Indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East (SIP). A list of these peoples was approved by Order No. 536-r of the Russian Federation Government of April 17, 2006. According to the census, in 2010 1,150 Shor people lived in Khakassia; as a June 1, 2021, 629 Shor people lived in places of traditional residence and activities in Askizsky and Tashtypsky districts (data from the Republic of Khakassia government: https://r-19.ru/news/obshchestvo/117764/). In 2010, 10,672 Shor people lived in Kemerovo Oblast, Kemerovostat data on the Shor people: https://kemerovostat.gks.ru/news/document/94818.

The problem of river pollution from gold mining has extended beyond Shor territories of traditional residence. According to a recent study conducted by 2Map of gold-mining plots and threats from them, https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap=08ff198cc70c45d2bec5f427d42213ed&extent=79.444,47.1261,107.8107,58.2256 Harmony with Nature, a regional social organization of Altai Republic, in conjunction with World Wildlife Fund (WWF) project People to Nature, 279 licensed gold-mining plots were identified in seven Russian regions as representing a potential threat to human beings and the environment: 12 were in the Altai Republic, 98 were in Buryatia, 5 were in Tyva, 11 were in Altai Krai, 99 were in Krasnoyarsk Krai, 32 were in Khakassia, and 22 were in Kemerovo Oblast. Some of the licensed plots in Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast are within the territories of traditional residence and activities of the Shor people or in close proximity to them. In May and June of 2021, WWF experts identified 3WWF Russia, results of monitoring bodies of water in Siberia on the basis of satellite photographs taken in May and June of 2021 below placer gold mining sites, June 8, 2021, https://wwf.ru/resources/news/altay/eksperty-wwf-vyyavili-30-faktov-zagryazneniy-rek-sibiri-protyazhennostyu-1474-km-ot-dobychi-rossypno/ 30 cases of complex river pollution resulting from placer gold mining in four regions of Siberia on plots along a total length of 1,474 km. Of these cases, five occurred along 203 km in Khakassia, and five were found along 218 km in Kemerovo Oblast.

The authorities also recognize that rivers have been polluted on a large scale: The government of Kuzbass asked the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment to suspend issuing licenses for subsoil use at placer gold deposits in regions of Kemerovo Oblast where violations had been identified. Under a decision of Russia’s Federal Agency for Subsoil Use, Kemerovo Oblast stopped issuing expedited licenses on the basis of an application and started holding tenders and auctions instead. 4Kuzbass stops issuing expedited gold-mining licenses, media report, July 16, 2020, https://tass.ru/ekonomika/8978003 In spite of this, the situationat least in the region’s south, on traditional Shor lands, has not improved. Field data collected by ADC Memorial show that in southwestern Khakassia and southern Kemerovo Oblast, gold mining is continuing under previously issued licenses with numerous violations of environmental protection laws, including the absence of water treatment facilities, unauthorized discharge of polluted effluent, the use of roads and parking areas in protected riverside areas, violation of water-use rules for water uptake, and so forth.

One would think that the places where the Shor traditionally reside, which is the subject of this report, would be protected from commercial exploitation. The Shor villages of Balyksa, Neozhidanny, Nikolaevka, and Shora in Askizsky District, Khakassia, and Orton, Ilynka, Uchas, and Trekhrechye villages in Mezhdurechensky Municipal District of Kemerovo Oblast were added to the Federal List of Places of Traditional Residence and Activities of Small Indigenous Peoples. 5Order No. 631-r of the Russian Federal Government of May 8, 2009, “On the Approval of a List of Places of Traditional Residence and Traditional Activities of Small Indigenous Peoples of the Russian Federation and a List of Traditional Types of Economic Activities of Small Indigenous Peoples of the Russian Federation, https://docs.cntd.ru/document/902156317 In 2016, Shor lands within Khakassia were included within the borders of specially protected territories of traditional nature use, 6Order of the Republic of Khakassia Government No. 508 of October 21, 2016, “On the Formation of Territories of Traditional Nature Use of Small Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation Residing in the Republic of Khakassia of Regional Importance, https://r-19.ru/documents/postanovleniya-pravitelstva-respubliki-khakasiya/34061/ where any activity that threatens the condition of natural resources is prohibited. In this regard, the question of the property rights of Indigenous peoples to their traditional territories and their official registration remains open: Contrary to international standards, the Russian law on small Indigenous peoples does not recognize their right to own traditional territories and only enshrines their right to use the land free of charge and participate in monitoring the use of various categories of land (Art. 8 of the Federal Law “On Guarantees of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the Russian Federation”).

In reality, the Shor have been almost completely excluded from the process of whether or not to put a territory of traditional activities up for auction. Gold-mining companies have no trouble acquiring the right to develop placer mines within these territories and bear virtually no liability for numerous violations of environmental laws, while Indigenous residents do not receive fair compensation for damages. The Shor use their native lands on the basis of traditional law, which is not legally recognized in disputes with commercial companies.

Traditional Shor lands are extremely attractive to gold-mining companies, since they include the largest placer gold deposits, whose gold can be enriched and processed more easily and cheaply than gold from ore rock. Over the past five years, the scale of gold mining and the number of gold-mining cooperatives in Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast have increased. This became especially noticeable in 2020, when the price of gold exceeded $2,000 per ounce and most companies stepped up their mining, including by discovering new deposits.

At the time of this writing, eight placer mines were operating in close proximity to Shor villages. In Khakassia, these include the plots Magyzinskaya ploshchad and Balyksinsky (the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative); the plot Bolshoy Nazas and the Aleksandrovsky stream (the Iyusskaya Gold-Mining Cooperative), and the plot Izassky (Izas Company). In Kemerovo Oblast, these include a plot on the Zaslonka River (Pay-Cher 2 company), a plot on the Orton River (ZER company), a plot on the Fedorovka River (AS Gornaya), and a plot on the Bazas River (Novyi Bazas company). We have information that other companies have already received licenses to perform geological exploration work – local residents have no doubt that mining will following this exploration work.

Russian law does not even require an environmental impact assessment for a license to mine gold. Naturally, the entire population suffers from mining’s impact on nature. At the same time, environmental pollution and destruction have catastrophic consequences for the Shor because they are particularly dependent on the ecosystem and on the preservation of flora and fauna, which provide the foundation for their traditional livelihoods and diet. The main environmental problems caused by placer mining on traditional Shor lands are:

- destruction of the fertile layer of topsoil;

- pollution of the soil with industrial waste;

- changes in the migration paths of wild animals due to the construction of dumps, ditches, and service roads.

- noise pressure during the operation of mining, automotive, and auxiliary equipment leading to the migration of wildlife populations;

- pollution of the atmosphere with harmful emissions from mining, automotive, and auxiliary equipment, as well as dust from waste dumps, ore stockpiles, and ore roads;

- pollution of rivers with unpurified technical water, use of bodies of water without permits or contracts for water use, unauthorized transfer of part of bodies of water without the corresponding transfer of land;

- no remediation of disturbed lands.

The destruction of the natural environment by gold-mining companies is not accidental, but is systemic in nature: Companies try to minimize their losses and ignore the requirements of environmental law.

One common argument in favor of the commercial exploitation of traditional Indigenous lands is that mining companies contribute to regional budgets and promote regional well-being and socioeconomic development. This, however, is misleading: While causing so much harm to the territories where the Shor traditionally reside, almost none of the abovementioned gold-mining companies are registered with the municipal districts where they process the subsoil. Of these companies, only two are registered where they operate – Izas, in Khakassia and Pay-cher 2, in Kemerovo Oblast. All of the other companies are registered in Krasnoyarsk Krai and pay taxes to the federal budget and the budget of the constituent entity where they are registered.

ADC Memorial field studies show that, contrary to statements made by government and company representatives, commercial exploitation does not improve the level or quality of life for small Indigenous peoples and actually only worsens their situation.

At the same time, neither regional nor federal environmental agencies are able to stand up against the harmful legal and illegal activities of gold-mining companies. This is because the gold-mining areas are remote and hard to reach, technical support is poor, and the agencies themselves have no authority to monitor these companies, which are supported by, and often affiliated with, the government. Therefore, an increasing number of licenses are being issued for placer mining on plots in close proximity to specially protected territories of traditional nature use or areas in river basins that flow through these territories.

Residents of Shor villages have had to fight violations of environmental law on their own. They come under pressure from both mine workers and representatives of the government and supervisory agencies that oversee the activities of mining companies:

“The chief inspector of the forestry agency threatened to open a criminal case against me for slander and told me to write a statement for the agency. She believed that I did not have evidence that the forest was being cut down illegally; she alleged that no trees were harmed, even though we recorded felled cedar trees on video. When we posted this video, cooperative workers came to my home when I wasn’t there. When they didn’t find me, they went to my friend, who went to the placer mine with me and recorded the violations, at work. They immediately started speaking very rudely to him and threatened to deal with us. They asked why we were filming their site and why we were getting involved in their business.

Several days later, we formed an advocacy group made up of members of the Shor community, environmental activists, and the social inspector from the Federal Service for Supervision of Natural Resource Usage and went back to the mining plot. We recorded many more violations in the mine’s operation. We showed the head of the cooperative, Anton Dudarev, the dirty water that was running down from the quarry right into the river, but he said that the water was cloudy because of the rain that had fallen. After a protracted debate, Dudarev promised to coordinate every step with the residents of the Shor villages. He also said the water would be clean.

The next day, Dudarev and his associate came to my home and asked me to estimate the amount of damages that the cooperative had caused to my hunting grounds – but they had driven in their equipment, ruined the fertile layer of the soil, chopped down the forest, including the cedars, dug out a new riverbed for the Bazas River, and put up a barrier on the only road leading to these lands. They also asked the activists to stop writing critical materials and posting videos of the violations online. They promised that they would compensate me for damages so that we wouldn’t cross paths again, as they put it. I told them that they should resolve these matters with all the residents who had been harmed by their activities and then with me, if they wanted to talk to me separately. They didn’t get what they wanted from me, so they left, and I haven’t had any contact with them again.

The river is still being polluted. The embankment dam at the placer mine does not meet construction codes and regulations, so polluted water is draining into the Bazas River. They still don’t have settling basins for the water; because they are constantly changing the river’s course, they apparently decided not to waste time and money on this. So we have not been able to have them prosecuted, and the agencies for supervision of natural resource usage are simply closing their eyes to this”

Resident of Orton Village. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

The Shor themselves speak about the catastrophic consequences of gold mining – the destruction of their traditional living environment and nature use, the change in their way of life, and the loss of their identity and culture:

“Even though we have converted to Christianity, our life is still inextricably connected with shamanic traditions, and an important role in our rituals is played by the place that was chosen by our ancestors centuries ago based on certain signs. This place practically never changes and serves as a place of worship for all the descendants. The loss of such a place by unnatural means and the inability to hold rituals there is a spiritual disaster for the Shor.”

O., resident of Trekhrechye Village, Kemerovo Oblast. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021.

This report is based on field data collected by ADC Memorial in June 2021 and open source materials. ADC Memorial would like to express its gratitude to the members of the Indigenous peoples and local communities of Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast and the experts, activists and environmentalists who provided information for this report.

Violations of Shor rights to land and resources

There are fewer and fewer places to mine for placer gold in Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast. The lands of interest to the mining companies mostly border agricultural or hunting lands where generations of Shor have raised animals, foraged, hunted, and fished for centuries. These types of activities and trades are the only source of income for the Shor, since there are generally no jobs in the compact areas where they live. Because of this, most of them have spoken out against gold mining and refuse to transfer ownership of their lands to gold-mining companies, which, in turn, are attempting to gain possession of new land by any, and often illegal, means, violating the individual and collective rights of Indigenous peoples.

The UN Declaration on the Protection of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, ILO Convention No. 169, and customary international law enshrine the right of Indigenous peoples to land, territory, and other resources. The ILO convention uses the term “lands” to include the total environment of the areas which Indigenous peoples occupy or otherwise use. They have the right to ownership, possession, use, development, and control of the lands, territories, and other resources they possess on the basis of traditional rights and other forms of traditional possession or use 7Indigenous peoples’ collective rights to lands, territories, and resources. The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Indigenous peoples’ collective rights to lands, territories and resources: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/04/Indigenous-Peoples-Collective-Rights-to-Lands-Territories-Resources.pdf

Russian law does not stipulate that Indigenous peoples have collective property rights to land: Under Article 8 of Russian Federal Law No. 82-FZ of April 30, 1999 “On Guarantees of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of the Russian Federation,” in order to protect their ancestral living environment and traditional lifestyles, activities, and trades, small Indigenous peoples and associations of small Indigenous peoples have the right to use, including at no charge, common mineral deposits and various categories of land in areas where they have traditionally lived and been active that are vital to them for pursuing their traditional activities and trades. The Land Code (Article 39.10.13) establishes a timeframe of 10 years for this free land use. Clause 5, Article 10 of Federal Law No. 101-FZ of July 24, 2002 “On Agricultural Land Transactions” stipulates that state and municipal agricultural land plots cannot be transferred to small Indigenous communities and that these lands may only be leased. Article 7.3 of the Land Code states that a special legal regime may be established for land use – namely, territories of traditional nature use – in places where small Indigenous peoples and ethnic communities traditionally reside or are active. These territories are regulated by a special law, No. 49-FZ “On Territories of Traditional Nature Use of Small Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation,” which has been widely criticized. Amendments to this law, which have also been sharply rejected by experts and members of Indigenous peoples, have been stalled for several years.

Land rights and the right to property are generally protected as individual rights by the Civil and Land codes. Some additional guarantees that are not related to the special status of Indigenous peoples are granted by environmental protection laws.

In addition, several regions of Russia (Krasnoyarsk Krai, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District, Sakha Republic (Yakutia)) have special laws to protect the ancestral lands and traditional lifestyles of Indigenous peoples that regulate the activities of federal and local agencies and legal and natural persons to preserve the traditional natural areas, activities, and lifestyles of small Indigenous peoples. 8Law of Krasnoyarsk Krai No. 11-5343 of November 25, 2010 “On the Protection of the Ancestral Lands and Traditional Lifestyles of the Small Indigenous Peoples of Krasnoyarsk Krai,” https://docs.cntd.ru/document/985020863; Law of Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug No. 49-ZAO of October 6, 2006 “On the Protection of the Ancestral Lands and Traditional Lifestyles of the Small Indigenous Peoples of the North in Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug,” https://docs.cntd.ru/document/802075618; Law of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia) 897-Z No. 715-IV of March 1, 2011 “On the Protection of the Ancestral Lands and Traditional Lifestyles, Activities, and Trades of the Small Indigenous Peoples of the North in Sakha Republic (Yakutia): https://minimush.sakha.gov.ru/uploads/ckfinder/userfiles/files/897-%D0%B7.rtf

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples enshrines the fundamental principle of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), that is, the right of Indigenous communities to fully and effectively participate in the adoption of any decisions, whether legislative or administrative, that affect their lands. Observation of this principle of is a necessary condition for managing any activity relating to traditional lands, territories, and other resources.

Even though Russia abstained from voting to adopt this declaration at the General Assembly in 2007, it did accede to the outcome document of the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples in 2014. The preamble of this document contains the Russian government’s affirmation that it will adhere to the norms of the Declaration. Russia has repeatedly said that it is conducting its Indigenous policy in accordance with the spirit of this declaration. In particular, in its 2019 report on its implementation of recommendations made by the UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, the Russian government wrote that if follows the principle of FPIC in relation to small Indigenous peoples.9nformation received from the Russian Federation on its subsequent activities related to UN CERD’s Concluding Observations on the twenty-third and twenty-fourth periodic reports of the Russian Federation, May 21, 2019, CERD/C/RUS/CO/23-24/Add.1.

It is true that individual provisions of FPIC are included in various regulations and legal acts. For example Article 39.14 of the Land Code establishes that land plots in areas where small Indigenous peoples traditionally reside can only be granted to business entities with account for the results of citizen assemblies and referendums, because this affects theses people’s legal interests. The need for members and associations of small Indigenous peoples to participate in the adoption of decisions affecting their rights and interests is mentioned in the Roadmap for the Sustainable Development of Small Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation, which was approved by order of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 132-r of February 4, 2009. Elements of FPIC are also present in town planning laws, which ban mining on agricultural lands. For mining to be possible from a legal standpoint, Article 5.1 of the RF Town Planning Code requires local governments to make changes to their locality’s land-use plan and general plan that must be coordinated with the local population through public discussions and hearings.

Nevertheless, FPIC principles are not observed. Since the law does not recognize FPIC and does not provide a mechanism for its application, officials and members of the business community can act in an arbitrary manner. With help from affiliated government agencies, mining cooperatives receive permits to mine gold without involving the Shor, who are directly affected by this, in any discussions.

Askizsky District of the Republic of Khakassia: illegal gold mining on territories of traditional nature use

n the fall of 2020, the Balyksinsky plot was opened under a license for gold mining. This plot, which is owned by the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative, is in close proximity to the Shor village of Neozhidanny in Askizsky District, Republic of Khakassia. The placer mining plot Magyzinsky, owned by the same company, is located three kilometers from Neozhidanny, in the mouth of the Magyza River. Both plots are located on lands that were added to the register of territories of traditional residence and nature use in 2016 under Order No. 508 of the Government of the Republic of Khakassia of October 21, 2016. A territory of traditional nature use is a specially-protected territory formed for small Indigenous peoples to follow a traditional lifestyle; any activity that threatens the condition of natural habitats and objects and harms the environment is banned.

Neozhidanny residents only learned that these lands had been given to gold-mining cooperatives when heavy equipment appeared in close proximity to their living zone and industrial work and forest clearance started. The agricultural plots of many of the village’s residents were destroyed, and the only road leading from the village to the cemetery and places for hunting and foraging in the woods was blocked by a checkpoint that only workers were allowed through:

“A place in the forest not far from Innokentyevka, where the mining cooperative is now, was where we collected mushrooms, berries, and cones until December 2020. We also used this road to reach our ancestral cemetery. It was about five kilometers as the crow flies from the village. They have now set up a checkpoint and aren’t letting anyone through except for the gold prospectors. They’ve completely ruined the soil and knocked down the cedars, which are not allowed to be touched. You can’t even reach the cemetery. Now we have to take a detour, which is about 10 to 15 kilometers. I personally can’t make it there because I’m already old, and we don’t have any off-road vehicles, so I don’t know how we will survive now. Until last year, we took part of the wild herbs we gathered to Mezhdurechensk and Novokuznetsk, where we sold them at the market, and that saved us. We were even able to put away some money. No one has a job here, so I don’t know what will become of us now”

A., resident of Neozhidanny. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021.

The gold-mining company later removed the barrier from the road, but the road was still blocked by a deep ditch. Local residents are not allowed to walk or drive along a detour built by the company.

The Shor felt the destructive consequences of the gold miners’ activities immediately:

“The Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative started using the Magyza plot without coordinating its plans with the local residents of Neozhidanny, even though our hunting areas and meadows are located there.” In my meadow, they used bulldozers to remove the topsoil – the fertile layer – and turned over the earth, making lots of deep holes and mounds and bringing rocks up to the surface. That place belonged to my grandfather. We prepared hay there for decades, my livestock grazed there, and now nothing grows properly there and haymaking is impossible. The livestock fall into the holes and injure their hooves. At the same time, this is a territory of traditional nature use, and no exploration work is allowed there, especially using heavy equipment. The fertile layer won’t come back for 100 years”

A.K., resident of Neozhidanny. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021.

In an attempt to learn how the authorities allowed the gold-mining cooperative to start exploiting plots in close proximity to a Shor village on a protected territory of traditional nature use without the approval of the Indigenous population, Yuri Kiskorov, head of the Shor community Altyn, and other residents of Neozhidanny turned to the administration of the Balyksinsky Rural Council, which their village was a part of. Administration head Vladimir Zavalin said that the subsoil license was issued by the Subsoil Use Department for the Central Siberian District in accordance with the law and that he had the minutes of public hearings on implementation of the law on territories of traditional nature use in Askizsky District from April 26, 2017. He went on to say that during this meeting, all the residents of the Balyksinsky rural settlement allegedly discussed changing the territory’s border and allowing the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative to explore and mine for placer gold on the Balyksinsky and Magryzinsky plots. He also said that all the residents of the rural settlement, including the residents of Neozhidanny and Kiskorov himself supposedly voted in favor of developing the deposit. However, not one single resident of Neozhidanny participated in the hearings or even knew about them to begin with. And Zavalin himself refused to show Kiskorov the minutes:

“On June 1, 2021, I went to the Balyksinsky Rural Council, where the hearings were held, even though hearings on important matters are held separately in each locality. Administration head Zavalin promised that he would give me the minutes of the 2017 vote, which, he said, showed that all the residents of Neozhidanny voted in favor of developing the Balyksinsky gold field and the Magyzinsky plot. Zavalin met me and said that he wouldn’t give me the minutes, because that was an official document that I could only obtain by filing an official request with the Askizsky District Administration. He asked: ‘Why do you need the minutes?’ I told him I needed to know which Neozhidanny residents had signed. This made him nervous, and he said that everyone from the village signed, including me. He said that he personally saw me there. But, like the other village residents, I wasn’t there because we didn’t even know about these hearings. If we had known, every single one of us would have voted against it”

Yu. Kiskorov, head of the Shor community in the village of Neozhidanny. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021.

Right after Kiskorov complained to the administration, Sergey Kovalkov, the general director of Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative, arrived in Neozhidanny. He accused residents of stoking the conflict and promised that the cooperative would clear any actions with them. He also offered to provide an apartment to anyone who wanted one and asked residents to put together a list of names indicating where each person would like to move. Understanding that the village, surrounded as it was by placer deposits, was doomed to die out, many residents agreed to move to the city. However, lawyers from the cooperative soon arrived with the much less appealing proposal of buying the villagers’ homes at their cadastral values, which, considering the conditions of the housing and the village’s remote location, were no more than several tens of thousands of rubles.

The Shor community filed a complaint with Khakassia’s prosecutor’s office and Ministry of Ethnic and Territorial Policy regarding violation of the federal laws “On Guarantees of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation” and “On Territories of Traditional Nature Use of Small Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation” by the head of the Balyksinsky Rural Council and the head of the Balyksinsky forest district. The complaint said that the results of the public hearings were falsified and that the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative was illegally mining on the plots.

The lawyer representing the villagers in their dispute with the rural council and the cooperative filed a request to suspend the cooperative’s activities with the prosecutor’s office and also sent a letter to the Republic of Khakassia’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment explaining that the company was mining on a territory of traditional nature use and sidestepping FPIC in the process. In its official response of April 27, 2021 (ADC Memorial has a copy of this letter), the ministry, like the rural council head, cited the minutes of the public hearing held on May 26, 2017, in accordance with which the land on the licensed plots Balyksinsky and Magyzinskaya ploshad were granted to the subsoil user after it obtained the prior and informed consent of the local residents. An announcement about these hearings was published in the official local newspaper – Askizsky truzhenik – on April 17, 2017, but no residents in Neozhidanny subscribe to this paper, so they had no way of knowing about the upcoming meeting.

Aside from suspending the cooperative’s work and holding new hearings, a way out of this conflict between local Shor and the subsoil user might be financial agreements that would offer compensation to the owners of ancestral lands and spell out actions that local self-government bodies could take to improve socioeconomic and infrastructure development in localities affected by gold mining. But no such agreement has been signed. According to the lawyer who represents the Shor:

“The official media outlet of Askizsky District is the “Askizsky truzhenik” newspaper. We went to their office and found the issue from April 17, 2017 that contains the announcement about the Balyksinsky Rural Council’s hearings on granting land plots to the gold-mining company and changing the borders of the territory of traditional nature use, on problems of enforcement related to territories of traditional nature use, and the signing of a trilateral social partnership agreement between Shor communities, the rural council administration, and the subsoil users operating on the rural council’s territory. This agreement should have outlined the mining companies’ responsibility for various violations, the amount of compensation due to local residents for this company’s work on the territory of traditional residence of a small Indigenous people, and so forth.

According to our information, no such trilateral agreement exists, even though it should be the main condition for gold-mining companies to access the plot. No resident in Neozhidanny saw or signed an agreement, even though mining is in full swing. We had a dialogue with representatives from the cooperative and the administration over the winter and spring of 2020. The company initially took the position that all of the village residents could be relocated. This continued until May 2020, when the cooperative announced that resettlement was not part of their plans and that it would help the population in other ways. The cooperative used those several months to become firmly entrenched in these places and now has no intention of leaving until they have worked through the entire plot.

Lawyer from Rodnaya Step. Interview with ADC Memorial, village of Neozhidanny, June 2021.

In this way, the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative was granted permission to mine for gold on the Balyksinsky and Magyzinskaya ploshchad plots by sidestepping FPIC and without obtaining the consent of the residents of Neozhidanny. The fact that territories of traditional nature use are mentioned in federal law did not guarantee the rights of the Shor.

In June 2021, a Shor representative received an official response from the Ministry of Ethnic and Territorial Policy of the Republic of Khakassia (ADC Memorial has a copy of this document). In particular, this document mentions that, aside from tax payments, the cooperative was providing support to local Shor “at its own initiative” (and not under some kind of contract) (the amount of charitable aid provided between 2016 and 2021 is estimated at almost 3 million rubles; the type of support provided included financing to make Shor national costumes and musical instruments and trips to a forum of teachers of small Indigenous peoples). The cooperative is also planning to help repair homes and supply firewood. The document also discusses plans to sign an agreement on compensation for damages to small Indigenous peoples in 2021.

From the Ministry’s official response, it appears that no trilateral agreement on the use of Shor territories of traditional nature use was ever signed, which leaves the Indigenous community dependent on the “initiatives” of the gold-mining companies. Article 8.2.8 of the federal law protecting Indigenous rights guarantees compensation for damages to the ancestral lands of small Indigenous peoples caused by the commercial activities of organizations or individuals, but the residents of Askizsky District have not received any such compensation.

Wise after their bitter experience dealing with various gold-mining companies, residents of Askizsky District are now trying to block new companies planning to operate on their territories. The first step is geological exploration. The consent of local residents is not required to obtain a license for this. Assemblies of residents supposedly intended to gain their “consent” for geological exploration are a farce. Residents are justified in feeling aggrieved, since they are confronted with a fait accompli, and their opinion is ignored. What typically happens is that a company representative tries to assure residents that he is prepared to hear them out and follow their wishes, but the company will start work anyway because it has already received an license for exploration. The head of the local administration accepts admonitions from all the parties and then makes excuses. Finally, a representative from the Natural Resources Ministry calls on everyone to dial down their emotions and records some kind of consensus in the minutes, and so forth. This format leaves a lot of room for manipulation (for example, they invite a member of the Shor community from a neighboring district whose role is to describe positive examples of cooperation between Indigenous communities and the “prospectors,” people voice their support, ask for houses of culture and gyms to be built in exchange for permission to operate, and propose forcing other companies to pay compensation before allowing new companies in, while company representatives respond that they have no intention of answering for others, and so on and so forth).

An assembly for residents of the Balyksinsky rural settlement was held in July 2021. The administration head told attendees that two companies had been issued licenses for geological exploration. A representative from only one of these companies – Sibresursy, which is registered in Abakan – was present. He assured residents that he had sent all the documents to the administration one month earlier, but this was the first time residents were hearing which specific plots had been allocated for exploration. The company was only nominally asking for permission for these operations, since it had already received the license it needed. The residents were categorically against the exploration, but it’s doubtful that their opinion will be taken into account. They left the meeting deeply disappointed.

Shor villages of Mezhdurechensky Municipal District of Kemerovo Oblast: gold-mining in localities on the federal list of places of traditional residence of small Indigenous peoples

An identical situation with violation of FPIC principles occurred in Kemerovo Oblast, where territories of traditional nature use for small Indigenous peoples have not been formed at the level of federal constituent entity as they have been in the Republic of Khakassia, even though representatives of Indigenous communities have lobbied the government for this over the past five years. Since 2017, the Council of Elders of the Shor People has appealed to the governor of Kemerovo Oblast three times with a proposal to include the Shor villages of Mezhdurechensky Municipal District located in areas with a large number of industrial mines in a territory of traditional nature use. Progress in this matter was only achieved after the Council of Representatives of Small Indigenous Peoples under the Governor of Kemerovo Oblast and, within the council, the Working Group on Pressing Matters of the Sustainable Development of Small Indigenous Peoples of Kemerovo Oblast were created in late 2019. In February 2020 that the Working Group adopted a decision to create one more working body – an interagency group on the formation of a territory of traditional nature use. In May 2020, the Council of Elders of the Shor People launched a legislative initiative 10Draft law “On the Introduction of Amendments to Article 26 of the Bylaws of Kemerovo Oblast – Kuzbass” prepared by the grassroots movement Council of Elders of the Shor People of Kemerovo Oblast and sent to governor of Kemerovo Oblast S.E. Tsivilev and chair of the Kemerovo Oblast legislative assembly V.A. Petrov on May 12, 2020. http://shor-people.ru/news/proekt-zakona-o-vnesenii-izmenenij-v-statju-26-ustava-kemerovskoj-oblasti-kuzbassa.html to add an FPIC provision to Article 26 of the bylaws of Kemerovo Oblast, but this has not happened yet. In the fall of 2020, the Working Group proposed a pilot project for a territory of traditional nature use in the Ust-Kabyrza rural settlement of Tashtagolsky District, Kemerovo Oblast. The Shor we interviewed believe that this project is meaningless because Ust-Kabyrza is a remote territory and contains the Shor National Park. For this reason, Indigenous residents of Ust-Kabyrza would have no land on which to create a territory of traditional use.

Some Shor believe that officials are barring the creation of territories of traditional nature use in places that are attractive to mining companies. In addition, the authorities have no understanding that territories of traditional nature use cannot be arbitrarily created or moved to a different place:

“Our officials are too far removed from the lives of Indigenous peoples, so they don’t understand what a territory of traditional nature use actually is. This is the long-term, age-old process of pursuing a sustainable livelihood and protecting wildlife on family lands that have been handed down from father to son for centuries. It’s not a problem for them when a placer mine enters our territory and destroys the entire ecosystem and infrastructure that we built with our own hands over decades. We build hunting huts on plots, we build stoves, we make salt licks to provide additional nutrition so that the wild animals don’t leave. We only fish at certain times in places that are well-stocked. We cannot just pick up and go to a different plot that has been lived on and used by other people. But they can’t imagine this: there’s no hunting, and so? Go hunt in a different place. No fish? There are lots of other rivers around that have fish”

A. Chispiyakov, representative of the Shor community of Kemerovo Oblast. Interview with ADC Memorial. Village of Orton. June 2021.

Because they are not part of a territory of traditional nature use, the Shor villages of Orton, Trekhrechye, Uchas, and Ilinka, which have all been affected by gold mining, have been added to the Federal List of Places of Traditional Residence and Activities of Small Indigenous Peoples (approved by RF Government Resolution No. 631-r of August 5, 2009). In spite of these restrictions, in recent years the Subsoil Use Department for Siberia has issued at least three licenses for placer mining near Shor villages without holding any public hearings. One of the placer mines belongs to the Krasnoyarsk company Novy Bazas. A resident of Trekhrechye described the devasting effects this mine has had on the Bazas River.

“Trekhrechye has always been considered the most environmentally pristine Shor village. Now, thanks to the “prospectors,” the river is dirty. There are 26 houses in the village, and they all take water from this river. We don’t even have a well. This pollution will naturally have an adverse impact not just on the village residents, but also on the entire environment. Our domestic livestock drink water from this river, as do the game animals in the forest. But who is bothered by this? We didn’t even know that the cooperative had invaded our river. No one notified us. We only understood what was happening when we started seeing dirty water in the river. We appealed to the village council, and they told us that on the bright side the road would be clear in the winter. Well, they plowed the road when they brought in the equipment, but then they forgot about it. After the next snowfall, it was already impossible to get through”

Resident of Trekhrechye. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

The ambiguity of land rights also comes up in relation to hunting lands. On the one hand, Part 1 of Article 49 of Federal Law No. 52-FZ of April 24, 1995 “On Wildlife” envisages the right of people who are members of small Indigenous peoples of the Russian Federation to have preferential use of wildlife on territories of traditional settlement in places where these peoples have traditionally lived and conducted activities. On the other hand, Russian law places no restrictions on auctions and tenders for the right to lease forest areas and hunting lands in places where Indigenous peoples live, except when these territories are part of a territory of traditional nature use. This creates fertile ground for conflicts between Indigenous communities and private companies that have been granted the right to use these territories; it also creates the risk that hunting spots will be arbitrarily transferred to gold-mining companies.

In recent years, the Kuzbass Forestry Department has started auctioning off the right to enter into agreements to lease agricultural and hunting lands where the Shor have practiced their trades for centuries. Private companies that have won the right to own and use a plot in an auction often restrict the rights of members of small Indigenous peoples by preventing them from hunting or even entering the territory. A ban like this is catastrophic for Shor living in remote areas of Mezhdurechensky Municipal District, where there are no jobs or opportunities for earning a livelihood aside from traditional trades.

The Shor only learn that the gold-mining companies have seized their hunting grounds after the fact. One resident of Orton unexpectedly discovered that his hunting grounds were being threatened by the activities of Novy Bazas:

“The Shor have lived here since the beginning of time, even though the village of Orton was officially founded in 1969, when a colony settlement was built here. It was one of the dozens of logging colonies clustered along the upper reaches of the Tom and Mrasu rivers. They chopped down everything, including the cedars. Over the past 90 years, the area of cedar growth in Kemerovo Oblast has shrunk by a factor of 16. And where there are cedars, there are cones and nuts, which sable, badgers, bears, and other forest animals and birds, including game animals, eat. The more they chopped down the forest, the fewer wild animals there were. In addition, because of the abundance of moss and shade, the coniferous forest helped to retain water within the riverbed during flooding in the spring. As long as the prison colony was here, the forest did not reproduce, and now deciduous trees are growing in places where spruces, cedars, and fir trees once grew. The water is no longer being retained. Forest plots and housing settlements are being flooded. It’s the opposite in the summer. There are often periods of droughts, and bodies of water become shallow because of the lack of proper balance. This makes the water warm up faster. Whitefish, for example, do not live in warm water. There are many fewer fish.

The prison colony was closed in 2014, and quiet returned. The wild animals started to return to our forest and hibernate here, the river became cleaner. Biodiversity slowly returned. The peak was in 2018 to 2020. Fishing and hunting were very good. We gathered a fairly large quantity of berries. But this didn’t last long. In December 2020, the Bazassky gold-mining plot was opened on Petropavlovsk Stream. The placer mine company Novy Bazas started developing this plot. At first, none of the local residents knew about them. It was only in January that hunters told me that gold was now being mined in the river. However, there were no meetings or talks with me as the head of our community or with other local residents, even though Orton is in a zone that is highly impacted by their activities. We did not receive any notices from the oblast or local administrations. Later, when the “prospectors” gave me a map of their licensed plot, I learned that my ancestral hunting grounds fell within its borders, along the Sunzas and Pistyk rivers, which meant that they would soon be ruined”

Resident of Orton. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

The settlement of Ilinka is 12 kilometers from Orton. It has the smallest population of all the villages in Mezhdurechensky Municipal District – only four Shor families live there year-round, and the rest of the houses are used as dachas. Ilinka found itself on the borders of Novy Bazas’s licensed plot, and the prospectors started work near the village in January 2021. They set up a “prospectors’ town” in the village, renting homes from local residents. Our informants told us that no official preliminary hearings were held – the miners and residents came to a verbal agreement that in return for housing the workers, the company would install lighting and plow the road to Orton, where the stores and official offices are, in the winter.

Ilinka has not suffered too much from the work at the placer mine yet, although in the summer of 2021 residents did note that the streams were becoming polluted from the heavy equipment that passed through. After the cooperative was opened, a barrier was put up across the only road connecting Ilinka with other localities. Residents believe that Ilinka may cease to exist when the placer mine moves closer to the village.

Violation of the rights of Shor people in Kemerovo Oblast and the Republic of Khakassia to a healthy environment

The right to a healthy environment has special significance for small Indigenous peoples because their traditional way of life, occupations, daily activities, and faith are inextricably connected with ecosystems and territories of residence and nature use. This is exactly why small Indigenous peoples are considered parties in legal relationships in the area of environmental protection and why this right is collective when applied to them.

The right to a safe, clean, healthy, and stable environment is not recorded as such in international standards and human rights treaties, but it is an important component of a number of other rights, including the right to life, to health, to decent living conditions, to housing, and to participation in cultural life and development. 11Framework Principles of Human Rights and the Environment, developed by the Office of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Environment, 2018) https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Environment/SREnvironment/FrameworkPrinciplesUserFriendlyVersion.pdf The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and ILO Convention 169 envisage the right of Indigenous peoples to preserve and protect the environment and the productive potential of their lands and to receive assistance and support from the government. The state must ensure that no hazardous materials are stored on the lands of Indigenous peoples without their free, prior, and informed consent (Article 29 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples).

In addition, to ensure a favorable environment for Indigenous peoples, the government must: recognize and protect the rights of Indigenous peoples to traditional lands, territories, and resources; consult and cooperate in good faith with Indigenous peoples through their representative institutions to comply with the principle of free, prior, and informed consent before taking or adopting any legislative or administrative measures that could impact them; respect and protect traditional knowledge and practices related to environmental preservation and sustainable nature use; and ensure that Indigenous peoples are given priority when receiving benefits from the commercial use of their lands, territories, and resources.

The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992) recognizes the vital role of Indigenous peoples in environmental management and development because of their knowledge and traditional practices and obligates states to recognize and support their identity, culture, and interests and enable their effective participation in the achievement of sustainable development. 12Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992), https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_CONF.151_26_Vol.I_Declaration.pdf

The Convention on Biodiversity (1992) calls on states to respect, preserve, and support the knowledge, innovations, and practices of Indigenous peoples relevant to conservation of biological diversity and the sustainable use of its components. 13Website of the Convention on Biological Diversity: https://www.cbd.int/

Aside from general constitutional guarantees (Article 42 of Russia’s Constitution), Indigenous peoples’ right to a healthy environment is protected by the federal law “On Guarantees of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in the Russian Federation,” which does not directly enshrine this right, but does envisage the right of Indigenous peoples to participate in monitoring compliance with federal and regional environmental protection laws when lands and natural resources are used for industrial purposes.

It is quite complicated to accomplish this kind of control over gold mining. In spite of the tremendous anthropogenic burden on virtually all components of the environment (the atmosphere, soil, water, flora and fauna), placer gold mining has been left off the list of activities requiring a state environmental impact assessment – which is the most important procedure from the standpoint of environmental protection that explains why licenses for prospecting, geological exploration, and development of a placer gold deposit must be obtained and provides for mechanisms to account for public opinion on one project or another.

Depriving Indigenous peoples of such an important tool for assessing potential environmental impact has weakened their dialogue with gold-mining companies. For Kemerovo Oblast, which has one of the unhealthiest environments in Russia, the fact that no mandatory environmental impact assessment is required for a gold-mining permit has led to deplorable consequences. In particular, the state program of Kemerovo Oblast “Ecology, Subsoil Use, and Sustainable Water Use” for 2017–2024 recognizes that the environmental situation in the region is strained and notes that long-term socioeconomic development scenarios for Kemerovo Oblast – Kuzbass envisage a heavier anthropogenic burden on all the components of the region’s natural environment. 14Collegium of the Administration of Kemerovo Oblast, Resolution No. 362 of September 16, 2016 on the approval of the state program of Kemerovo Oblast – Kuzbass “Ecology, Subsoil Use, and Sustainable Water Use” for 2017–2024, http://docs.cntd.ru/document/441678826

nother important tool for protecting the rights of small Indigenous peoples in their relationships with gold-mining companies could be an ethnological expert assessment, which is defined by Part 1 of Article 6 of the federal law “On Guarantees of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of the Russian Federation” as a scientific study on the impact of changes in the ancestral living environments of small peoples and the sociocultural situation on an ethnic group’s development. However, even though there is a general agreement on the need for the Russian government to conduct ethnological expert assessments, the procedures for completing one have yet to be enshrined in the law. Right now these kinds of assessments are only being done by enthusiastic volunteers, and their conclusions are rarely taken into account during projects that impact or could impact not just the natural environment of small Indigenous peoples, but also their traditions and lifestyle.

Experts emphasize the importance of traditional foods for Indigenous peoples. 15L.S. Bogoslovskaya, doctor of biological sciences, former director of the Likhachev Russian Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage’s Center for the Traditional Culture of Nature Use. “Traditsii pitaniia kak sposob adaptatsii k okruzhaiushchei srede” in Korennye narody rossiiskogo Severa v usloviakh klimaticheskikh izmenenii i vozdeistvii promyshlennogo osvoeniia, Seriia: Biblioteka korennykh narodov Severa, No. 16 (Moscow, 2015): 41-47. Scientific studies have shown 16Genomic Evidence of Local Adaptation to Climate and Diet in Indigenous Siberians, by Brian Hallmark, Tatiana M. Karafet, Ping Hsun Hsieh, Ludmila P Osipova, Joseph C Watkins, Michael F Hammer. 2019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30428071/ that depriving Indigenous peoples of access to their usual food and shifting them to a so-called “European lifestyle” heavy on carbohydrates poses a risk to Indigenous residents of Siberia:

“A study of Indigenous peoples was done with the participation of the Shor, Yakut, and Khakass peoples. They were compared with Novosibirsk residents in terms of how the gene responsible for moving and burning fats within the body works. It turns out that Indigenous peoples process fats more quickly. Unsurprisingly, the research concluded that fatty foods have been the main part of these Indigenous groups’ diets for centuries and that their ethnicities have adjusted in such a way that they digest fatty foods faster. So, if we deprive these groups of high-quality fats and protein, they will not be able to get enough energy from simple carbohydrates. An excess of carbohydrates leads to a chain of illnesses – cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, and so forth.

Fertility may be lowered with a change in food. Science has no direct evidence of this because there haven’t been any studies on it, but logically this is very likely. For Shor, whose numbers are already small and who are highly assimilated, the process of changing diet may be an additional factor in the drop in population.

Olga Gulyaeva, senior research associate of the Novokuznetsk Institute of Occupational Health. Interview with ADC Memorial

Air pollution, destruction of flora and fauna during gold mining

The most common method for exploiting placer gold deposits is open-pit mining, which has a major anthropogenic impact of all the components of the environment. During mining and primary processing, a huge amount of pollutants are released into the atmosphere. These include suspended particulate matter, carbon disulfide, and nitrogen oxides. The equipment used in gold-mining operations causes dust and atmospheric gas pollution.

Bodies of water, the soil, and plant and animal life in particular are adversely impacted by placer mining. The loud noise caused by placer mine operations alarms forest birds and animals and forces them to migrate to remote areas that local residents cannot access. Hazel grouse, wood grouse, elk, and sable have almost completely disappeared from the forest areas bordering Shor villages because of gold mining. Many placer mines are located in the migration paths of hoofed animals like deer, moose, and others. During their seasonal migrations in the spring and fall, the noise from the mines and the changed landscape causes animals stress and forces them to look for new places to live, which has a very negative impact on their ability to reproduce and their population levels. The number of birds and animals is dropping, and grasses and cones are disappearing because off the deforestation that precedes gold mining. And, naturally, fish cannot spawn in places where gold is being mined. Gold-mining also poses a serious threat to Red Book plants that grow in abundance on the territories of placer mines. These include Erythrōnium sibīricum, Lobaria pulmonaria, Menegazzia terebrata, Ramalina asahinana Zahlbr, and others.

Among other main principles of land law, the Land Code enshrines the priority of land protection as the most important component of the environment and agriculture. In addition, ruining land is an administrative violation under Russian law. The fertile layer of the soil, which has been formed over an extended period and reaches over one meter in depth in Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast, is ruined during geological exploration and gold mining. Mushroom foraging is becoming dangerous because the operation of heavy equipment poisons the soil with petroleum products.

“The fertile soil here, along the river’s course, is a half-meter to a meter deep, maximum. According to regulations, gold-mining companies have to remove this layer and set it to the side. After they have finished, they must put it back. But no one has done anything even close to this. They just destroy it, and then everything turns into dry desert. In the places where it was torn out, the fertile layer gets from one to five centimeters deeper every 100 years, so you can imagine what can grow there now – weeds and maybe some leafy plants at the most. Cedars, for example, definitely will not do well here, because they love moisture and they’re very capricious. If there aren’t any cedars, then Indigenous residents won’t have anything to live off of, because cedars are of extreme economic importance”

E.F. Tenesheva, senior inspector of the Mezhdurechensky Forest Department. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

Even during the exploration process, before mining actually commences, a huge number of ecosystems are ravaged. These include many agricultural plots like meadows and pastures that belong to communities of Indigenous residents. In the fall of 2020, exploitation commenced on the licensed plot of Magazinsky in Askizsky District, Khakassia. This plot is situated along the streambed of the Magaz River, two kilometers from the Balyksinsky plot, which was opened several years ago. Both places are on territories of traditional nature use of the Shor people, in close proximity to the Shor villages of Balyksa, Neozhidanny, Ust-Vesely, and others. Neozhidanny has suffered from gold-mining activities more than the others:

“We have four plots of ancestral meadows about 10 kilometers from Neozhidanny. Several generations of my ancestors prepared hay there for their livestock. When the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative reached us, they turned over two of the four meadows with their bulldozers in such a way that only stones and clay were left on these even fields, where lush grasses once grew. They did the same thing with our neighbors’ meadows when they were doing exploration work. They left mine holes and lumps of earth, they removed the turf. Now our neighbors have no idea how to prepare the hay or what to feed their livestock, and no one is going to compensate them for damages. They have five children, and the whole family basically lived off these meadows.

Aside from the meadows, the miners also ruined the road that goes from the village to the meadows and to the woods, where we all forage. Now the only way to get there is in a Ural jeep. Before the prospectors got here, there were two roads from the village to the forest. They have set up a checkpoint on one of them and do not allow local residents through. So we have been left without hunting, mushrooms, grasses, and cones, because it is almost 15 kilometers to the forest using the other potholed road.”

A., resident of Neozhidanny. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

In 2021, residents of the Shor villages of Orton, Ilinka, Uchas, and Trekhrechye, which are in Mezhdurechensky Municipal District, Kemerovo Oblast, had to contend with illegal geological exploration work conducted by the privately-owned gold-mining company Novy Bazas. An Ilinka resident who suffered from the company’s activities told us about the destruction of meadows and how they were polluted with construction waste:

“Our ancestral meadow is here. My family has made hay on this plot since 2005. We supported ourselves by selling this hay and earn about 300,000 rubles a year. We used it to feed our livestock. In February 2021, without our permission, the ‘propectors’ brought trash, rubble, and rotting beams from the old mine entrance here and spoiled a large part of the meadow. In two or three months, when they wrap up their work on the plot where they are now, they’ll come here and finish off the meadow completely, because this spot is part of their licensed plot. There are old workings a couple of kilometers from here, they’re about 30 years old. There also used to be meadows there, but it became a desert after the ‘prospectors’ were through with it. This place is only now slowly starting to reclaim itself – some small trees and weeds are starting to sprout. But they’re not suitable for livestock feed. A cedar grew 20 centimeters. We can see from this place what will soon happen with our meadow”

A. Resident of Ilinka, Kemerovo Oblast. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

Pollution of natural waters from gold mining

The list of rights to decent living conditions includes the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitary conditions, which is enshrined in international law, specifically articles 11 and 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It is also defined in General Comment No. 15: The Right to Water, which was issued by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2002, is indispensable for leading a life of human dignity. This means that states must ensure a sufficient amount of water that is both physically and economically accessible for personal and household use without discrimination.

Placer gold is mined in the upper reaches of rivers and affects many localities downstream. In Khakassia these include tributaries of the Tom – the Izas, Aleksandrovka, and Balyksu rivers – the Margyza River, which is a tributary of the Balyksu, and other small rivers and streams. In Kemerovo Oblast these are the Orton and its tributaries – the Fedorovka, Bazas, and others. These bodies of water are the most important form of sustenance for the Shor, because they are the only source of drinking water for Shor villages, livestock, and the wild animals of the taiga, which are the foundation of the Shor economy. The disappearance of fish deprives the Shor of an irreplaceable element of their diet, and the wild animals that eat the fish have to migrate to remote areas that hunters cannot access.

Under Article 20 of the Federal Law “On Subsoil,” the right to subsoil use may be terminated, suspended, or restricted prior to the scheduled date by the licensing bodies if a direct threat to the life or health of people working or living in the area impacted by the subsoil operations arises. Even though residents have complained and there have been clear cases of environmental pollution, the licenses of gold-mining companies operating near Shor villages have never been revoked or suspended.

These companies use natural waters for industrial and utility needs (hydraulic excavators, elevator pumps, or sluices that separate gold particles from the sand)

Under Russia’s Water Code, industrial waste cannot be discharged into bodies of water. Article 18 of the Federal Law “On the Sanitary and Epidemiological Well-Being of the Population” emphasizes that bodies of water used for drinking water or household purposes, including bodies of water within city and village limits, should not be the source of biological, chemical, or physical factors that adversely impact people. 17Federal Law No. 52-FZ of March 30, 1999 (amended July 2, 2021) “On the Sanitary and Epidemiological Well-Being of the Population” The law requires mining companies to build a number of technical hydraulic structures, some of which must be settling basins where processed water undergoes a multistage treatment to remove toxic substances.

The water quality in the rivers of Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast that are being mined for gold is worsening. In 2020, the water of the Balyksu River was found to exceed the maximum allowable concentration of pollutants like iron, copper, zinc, and petroleum products, as well as baseline indicators, by a factor of five. 18Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment of the Republic of Khakassia. Monitoring report on the state of environment components, http://minprom19.ru/deyatelnost/sostoyanie-zagryazneniya-atmosfernogo-vozdukha/ In June 2021, laboratory analysis showed that the level of zinc and other suspended particulate matter in the Balysku River was three times as high as allowed. 19Excessive levels of zinc and other hazardous substances were found in Balyksu River. Report of All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting citing the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment of the Republic of Khakassia. June 9, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=trsrXhiidOQ

The village of Balyksa, one of the places of traditional residence of the Shor, sits along this river. The gold-mining plot Balyksinsky, which is owned by the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative, is located in the upper reaches of the Balyksu River, several kilometers from the village. Residents say that the cooperative has been regularly discharging untreated water into the Balyksu since the placer mine started operations in 2020:

“In the winter, they collect water in so-called settling basins, which do not actually meet any construction codes or regulations These basins should have drainage ditches and, at a minimum, a three-tier system for purifying water in basins where this water should settle over the course of several months. Before the basins are filled with water, a special purification bed made of sand and clay in laid at the bottom to filter the water They currently only have one basin. As soon as the water in it reaches a critical level, it simply spills over the top and floods everything around. To avoid this, they dig a trench and release the water directly into the Balyksu. Residents from our village take water from this river, our livestock drink from it. In addition, at their base, which is above the outflow of water, they have fuels and lubricants without filters or traps, and all the petroleum products end up in this basin, and, from there, in the river.“

A.M., resident of Balyksa. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

In October 2020, the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative started mining the licensed plot Magyzinsky, which is located in the bed of the Magyza River, near Neozhidanny.This village is not equipped with water lines, and most residents take their drinking water from the Magyza and the main streams that feed into it:

“After they dump water at the placer mine, you can’t take water from the river – it turns some sort of reddish-brown color and smells of gas. Only 11 of the 45 homes in our village are connected to water lines, which our ancestors made by hand. The residents of the other 30 houses carry water from the river in buckets”

L.G., resident of Neozhidanny. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

In June 2021, the Yeniseyskoye Interregional Department of the Federal Service for the Supervision of Nature Use conducted an unscheduled check of the Magyzinskaya ploshchad plot. 20Data from the Unified Register of Checks from July 27, 2021, https://www.list-org.com/company/6084780 This check was based on the preliminary results of a check conducted by the chief specialist at the Department of State Environmental Supervision for the Republic of Khakassia following the complaint of a Neozhidanny resident. No violations were identified, but local activists did document pollution in the river. 21The pollution of the Tom River by its tributary, the Balyksu River, was caused by the operations of the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative. May 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ccICd_r6u7A

In Kemerovo Oblast, the gold-mining company Novy Bazas, whose licensed plot stretches for 32 kilometers, polluted the Bazas and Orton rivers, as well as their numerous tributaries and streams that supply the villages of Orton, Trekhrechye, and Ilinka with water. Many types of fish have suffered from the pollution of the rivers. Complaints from Orton residents have been ignored:

“A couple of months after the ‘prospectors’ started work, local fisherman discovered that the water in the Orton was terribly dirty. We went to the placer mine right away and found that they were pouring wastewater directly into the Bazas, which runs into Orton. There were no settling basins. We recorded this all on video and, at my initiative, sent complaints to head of the Mezhdurechensky District Administration Chernov and to the prosecutor’s office. Each complaint described violations like erosion of the Bazas River’s floodplains; improper operation of hydraulic manipulators, which meant that wastewater containing traces of petroleum products and suspended particles was dumped directly into the river; the absence of water treatment facilities; and the destruction of cedar trees. Every complaint was signed by residents of Orton and Trekhrechye. I also personally appealed to the governor of Kemerovo Oblast, Chernov. He never responded and forwarded my complaint to the head of Ortonov’s administration, L.I. Trukhina. After she reviewed my complaint, she organized a meeting of the rural council, to which she invited local residents and representatives of the administration and the forestry department. She read out our complaint and said that the violations we listed were unfounded.”

F.T., resident of Orton. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

In June 2021, environmentalists from Myski and residents of Orton discovered two drainage sources of polluted water from an embankment dam directly on the Bazas River:

“Dirty water started flowing in both Bazas and Orton at the beginning of summer. On June 5, 2021, I went with activists from Novokuznetsk and Indigenous residents from Orton to Novy Bazas’s licensed plot because that was the only possible source of river pollution in the area. We found an old tributary of the Bazas near the mine. In theory, this streambed should have been closed off, and it shouldn’t have had any water in it, but a yellow liquid was flowing in it. We climbed up to the place where the ‘prospectors’ have their embankment dam and found that dirty-colored water was draining directly into this tributary. We walked a little farther along the embankment dam and found another polluted stream of water that was also flowing directly into this tributary. About 100 meters later, all this water flowed right into the Bazas River. In theory, water should not flow from the embankment dam, which, according to regulations, should be filled with clay. This clay forms a kind of seal that prevents drainage. However, in this case the embankment dam was filled in with gravel, which water can easily pass through”

Environmentalist who travelled to the spot where the embankment dam failed. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

The Shor village of Trekhrechye has never had any waterlines or general infrastructure to support an acceptable quality of life. The entire population – just over 100 people – uses water from the river, so the pollution of their main source of water has adverse consequences:

he Novy Bazas Cooperative started bringing equipment to its licensed plot in December 2020 and had already started exploiting the plot by February. It’s about 10 kilometers from here, above the river. And then in February, the water in the Bazas River became cloudy, even though the water is usually crystal clear in the winter. I wanted to make a hole in the ice. I scooped out a small area and removed a piece of ice – it was some sort of reddish-brown color on the other side. And we have been using water from this river for centuries. We cook with it, drink it, give it to our livestock. Now it’s dirty and smells of diesel fuel. The water we collect in the morning smells especially strongly because the ‘prospectors”’pour dirty wastewater into the river at night, when no one can see. They don’t have a purification system there. They only have one settling basin instead of three, and it’s not enough. The fish I catch have also started smelling of diesel fuel. We have already had a few cases of poisoning in the village because of this. My grandson was vomiting and had diarrhea for three days. He’s now at the children’s infectious diseases hospital in the city. What can I say – the river is sick, and we are sick”

N., resident of Trekhrechye, Kemerovo Oblast. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021.

“Until 2014, there was a prison colony a couple of kilometers from here. The prisoners really ruined the nature while they were working – they sawed down the dwarf pines and scared the wild animals so much that they didn’t return to the forest for several years. They left a lot of trash behind them that the prison administration never even thought about removing. We couldn’t gather nuts or hunt while they were here. We barely survived. After the prison closed, nature slowly started coming back. Elk, moose, and mink reappeared, the bears returned. You can count, we lived pretty well for about five years. We could hunt, we started collecting cones again, the fishing wasn’t bad.

Now the gold miners have been working here since last year. They dug up the river, the forest is being chopped down again, and the animals have started disappearing again. My ancestral hunting grounds are right next to their placer mine. I have been hunting and fishing there for as long as I can remember. I went fishing three days ago, but there were no fish. The river was flowing with dirt and clay, but the whitefish need clean water. They don’t live in dirty water. So I’ve been left without fish. The forest animals are drinking from this river and dying, because the miners have poisoned it. If they keep pouring wastewater into it, the animals won’t stay here. I have seven children. I don’t know what I will feed them.

B.K., resident of Trekhrechye. Interview with ADC Memorial. June 2021

Residents in the small Shor village of Ilinka are accustomed to taking water from the river of the same name. Even though Novy Bazas’s operations are still quite far from Ilinka, residents are already suffering from the polluted air and water: