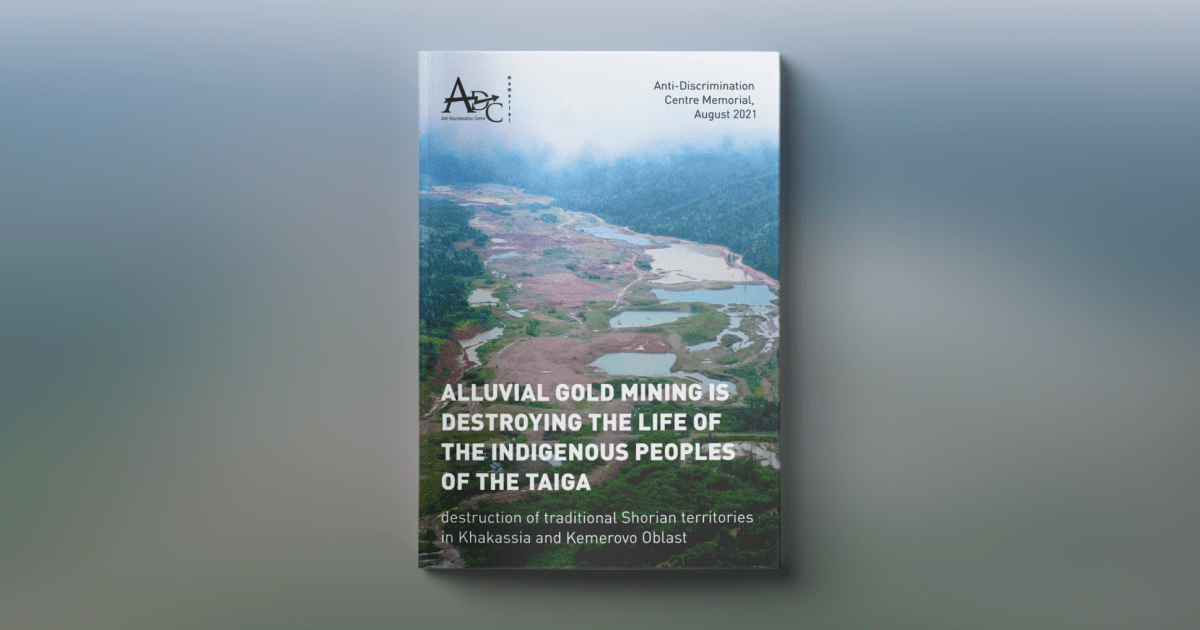

New Report to Mark International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples ADC Memorial on the Violation of the Environmental Rights of the Indigenous peoples of Siberia “Alluvial Gold Mining is Destroying the Life of the Indigenous Peoples of the Taiga”

One year ago, ADC Memorial published its first human rights report, “I Won’t Have Any Life Without This Land”, dedicated to violation of the environmental rights of the Indigenous peoples of Southern Siberia caused by coal mining and pollution of the air, water, and Indigenous lands. As it turned out, it is not just coal mining that adversely impacts the life, routine, and culture of the Indigenous peoples of Siberia: gold mining causes just as much harm and devastation to the traditional living environment of the Shor (a small Indigenous people) in Kemerovo Oblast and southern Khakassia. Private companies, which have no trouble getting a gold-mining license, pollute the environment, expropriate the land on which the Shor have led a traditional lifestyle for centuries, and destroy their cultural sites.

How this started

The history of placer mining in Russia began almost two centuries ago, when the mining engineer Lev Brusnitsyn discovered a method of washing gold-bearing sand in the basin of Berezovka River in 1814. Unlike lode gold, which was mined in Russia before Brusnitsyn’s discovery, placer gold is fairly easy to enrich and can be processed using the most primitive methods, which are accessible even to a person without special training or skills. This simple method set off Russia’s “gold rush.” It was during this time that most of the large, promising deposits of placer gold were found in the Urals, Chukotka, Altai, Transbaikal, Yakutia, and Siberia.

The search for and exploitation of placer gold deposits was one of the main reasons why these regions were settled by outsiders. At the same time, gold mining has an adverse impact on bodies of water, the soil, plant and animal life, and the ancestral territories of Indigenous peoples overall.

The plight of Shor on the taiga

An alarming situation has developed in recent years in the Shor villages of Balyksa, Neozhidanny, Nikolaevka, and Shora in Askizsky District, Khakassia, and Orton, Ilynka, Uchas, and Trekhrechye villages in Mezhdurechensky Municipal District, Kemerovo Oblast. These localities were added to the Federal List of Places of Traditional Residence and Activities of Small Indigenous Peoples and must be protected from commercial exploitation. In addition, Shor lands within Khakassia were included within the borders of specially protected territories of traditional nature use, where any activity that threatens the condition of natural resources is prohibited. Nevertheless, over the past five years, the scale of gold mining and the number of gold-mining cooperatives in Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast have increased. This became especially noticeable in 2020, when the price of gold exceeded $2,000 per ounce and most companies stepped up their mining, including by discovering new deposits.

At the time of this writing, eight placer mines were operating in close proximity to Shor villages. In Khakassia, these include the Magyzinskaya ploshchad and Balyksinsky plots , which are right next to Neozhidanny, the Bolshoy Nazas plot, the Aleksandrovsky stream, and the Izassky plot. In Kemerovo Oblast, these are plots located on the Zaslonka, Orton, Fedorovka, and Bazas rivers. All of these water bodies are the most important form of sustenance for the Shor, because they are the only source of drinking water for Shor villages, livestock, and the wild animals of the taiga, which are the foundation of the Shor economy. The disappearance of fish due to waste discharged into the rivers by the placer mines deprives the Shor of an irreplaceable element of their diet, and the wild animals that eat the fish have to migrate to remote areas that hunters cannot access.

Some of the main environmental problems Shor villagers have to deal with when placer mines are exploited include:

- pollution and destruction of rivers that are sources of drinking water for local residents and livestock;

- destruction of the fertile layer of topsoil on agricultural territories;

- pollution of the atmosphere with harmful emissions from mining, automotive, and auxiliary equipment, and dust from waste dumps, ore stockpiles, and ore roads;

- disappearance of wild animals of commercial value to the Shor.

Even during the exploration process, before mining actually commences, a huge number of ecosystems are ravaged. These include many agricultural plots like meadows and pastures that belong to Indigenous communities. In 2021, residents of the Shor villages of Orton, Ilinka, Uchas, and Trekhrechye in Kemerovo Oblast, had to contend with illegal geological exploration work conducted by the privately-owned gold-mining company Novy Bazas, which left agricultural lands decimated and polluted with construction waste. Identical violations of environmental laws were recorded in Askizsky District, Khakassia, where areas used for livestock grazing, haymaking, and berry- and mushroom-foraging were ruined as a result of the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative’s activities.

Destruction of the taiga ecosystem

Hazel grouse, wood grouse, elk, and sable have almost completely disappeared from the forest areas bordering Shor villages because of gold mining. Many placer mines are located in the migration paths of hoofed animals like deer, moose, and others. During their seasonal migrations in the spring and fall, the noise from the mines and the changed landscape cause animals stress and force them to look for new places to live, which has a very negative impact on their ability to reproduce and their population levels. The number of birds and animals is dropping, and grasses and cones are disappearing because of the deforestation that precedes gold mining. And, naturally, fish cannot spawn in places where gold is being mined.

Because gold is mined the upper reaches of rivers, water bodies are the most severely impacted. Residents of Askizsky District say that the cooperative has been regularly discharging untreated water into the Balyksu since the fall of 2020, when the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative started exploiting the Balyksinsky plot. In 2020, the water of the Balyksu River was found to exceed the maximum allowable concentration of pollutants like iron, copper, zinc, and petroleum products, as well as baseline indicators, by a factor of five. In June 2021, laboratory analysis showed that the level of zinc and other suspended particulate matter in the Balyksu River was three times higher than allowed. In June 2021, the Yeniseyskoye Interregional Department of the Federal Service for the Supervision of Nature Use conducted an unscheduled check of the Magyzinskaya ploshchad plot. This check was based on the preliminary results of a check conducted by the chief specialist at the Department of State Environmental Supervision for the Republic of Khakassia following a complaint from a Neozhidanny resident. No violations were identified, but local activists did document pollution in the river.

In Kemerovo Oblast, the gold-mining company Novy Bazas, whose licensed plot stretches for 32 kilometers, polluted the Bazas and Orton rivers, as well as their numerous tributaries and streams that supply the villages of Orton, Trekhrechye, and Ilinka with water. Water resources, including many kinds of fish, have suffered greatly from pollution. In one case, in the spring and summer of 2021 some residents of Trekhrechye got food poisoning from eating them. Local residents’ complaints to the district administration, supervisory bodies, and the prosecutor’s office were ignored.

The thing that poses the greatest danger for rivers is artificially shifting their course. Gold-miners use this technique to get as much gold as they can out of their licensed plot. They move the stream of water to the artificial riverbed and mine the gold remaining in the old riverbed. However, when they finish with the plot, they don’t move the riverbed back. This makes the rivers grow shallow and become polluted with toxic elements like petroleum products, manganese, and mercury, which has been in the soil since the times when gold was mined by hand. Changing the river’s course causes obstructions when the ice breaks up, which means that villages are flooded in the spring. In addition, during this process the bottom flattens out (becomes level) and the water starts to have less oxygen, which normally forms due to the many cavities, stones, and other natural objects on the riverbed. The river becomes warmer and is covered with blue-green algae in the summer, while the usual flora and fauna in it die.

A separate negative consequence of gold mining is flooded quarries, which form after the rock mass is removed and occupy huge territories. These quarries are deeper than the level of rivers, so water from all nearby bodies of water drains into them. Many artificial lakes start appearing where there were once forests and fields. In the spring, the water level in these lakes rises, causing flooding that wipes out terrestrial flora and fauna.

The gold-mining companies do nothing the restore the natural landscape to its original condition.

In addition, numerous dumping grounds and wastelands have formed on Shor territories of traditional activities because of gold mining. In accordance with current environmental protection laws, to reduce stress on the environment gold-mining companies must remediate the land (Article 13.1.6 of the Land Code). Expenses for remediation are the full responsibility of subsoil users. However, these large-scale and expensive works are generally never done after mining, in spite of the gold miners’ assurances that they have an interest in restoring nature to its previous state.

Under Article 20 of the Federal Law “On Subsoil,” the right to subsoil use may be terminated, suspended, or restricted prior to the scheduled date by the licensing bodies if a direct threat to the life or health of people working or living in the area impacted by the subsoil operations arises. Even though residents have complained and there have been clear cases of environmental pollution, the licenses of gold-mining companies operating near Shor villages have never been revoked or suspended.

Experimental remediation after gold mining near Ust-Vesely village. Photo: Vyacheslav Krechetov

Russian law does not require an environmental impact assessment for a license to mine gold, even given its significant, extensive impact on the environment.

Lack of prior informed consent of Indigenous residents

The Shor community has been almost completely excluded from the process of whether or not to issue a license for a territory of traditional activities. The Shor use their ancestral lands on the basis of traditional law, which is not recognized in territorial disputes, so gold-mining companies have no trouble acquiring the right to develop placer mines within these territories, and they bear virtually no liability for numerous violations of environmental laws, while Indigenous residents do not receive fair compensation for damages.

For example, exploration of the Magyzinskaya ploshchad and Balyksinsky plots, which belong to the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative and are located in close proximity to the Shor village of Neozhidanny, began without the permission or notification of local residents. Both plots are located on lands that were added to the register of territories of traditional residence and nature use.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples enshrines the fundamental principle of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), that is, the right of Indigenous communities to fully and effectively participate in the adoption of any decisions, whether legislative or administrative, that affect their lands. Observation of this principle of is a necessary condition for managing any activity relating to traditional lands, territories, and other resources. This principle is in effect in Russia, and individual provisions of FPIC are included in various regulations and legal acts. For example Article 39.14 of the Land Code establishes that land plots in areas where small indigenous peoples traditionally reside can only be granted to business entities with account for the results of citizen assemblies and referendums because this affects the legal interests of these peoples. The need for members and associations of small Indigenous peoples to participate in the adoption of decisions affecting their rights and interests is mentioned in the Roadmap for the Sustainable Development of Small Indigenous Peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation, which was approved by order of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 132-r of February 4, 2009.

Neozhidanny residents only learned that these lands had been given to gold-mining cooperatives when heavy equipment appeared in close proximity to their living zone and industrial work and forest clearance started. The agricultural plots of many of the village’s residents were destroyed, and the only road leading from the village to the cemetery and places for hunting and foraging in the woods was blocked by a checkpoint that only workers were allowed through. It later turned out that the subsoil use license had been issued by the Subsoil Use Department for Central Siberia and that public hearings about invoking laws on territories of traditional nature use in Askizsky District had been held in 2017 without Neozhidanny residents. However, according to Vladimir Zavalin, the head of the Balyksinsky Rural Council, which Neozhidanny is part of, all of the village residents voted in favor of exploitation, even though residents say that not one single one of them participated in the hearings or even knew about them to begin with.

In this way, the Khakassia Gold-Mining Cooperative was granted permission to mine for gold on the Balyksinsky and Magyzinskaya ploshchad plots by sidestepping FPIC and without obtaining the consent of the residents of Neozhidanny. The fact that territories of traditional nature use are mentioned in federal law does not guarantee the rights of the Shor.

With the help of a lawyer, Neozhidanny residents filed a request to suspend the cooperative’s activities with the prosecutor’s office and also sent a letter to the Republic of Khakassia’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment explaining that the company was mining on a territory of traditional nature use and sidestepping FPIC in the process. In its official response, the ministry, like the rural council head, cited the minutes of the public hearing, in accordance with which the land on the licensed plots Balyksinsky and Magyzinskaya ploshad were granted to the subsoil user after it obtained the prior and informed consent of the local residents. An announcement about these hearings was published in the official local newspaper – Askizsky truzhenik – on April 17, 2017, but no residents in Neozhidanny subscribe to this paper, so they had no way of knowing about the upcoming meeting.

Aside from suspending the cooperative’s work and holding new hearings, a way out of this conflict between local Shor and the subsoil user might be financial agreements that would offer compensation to the owners of ancestral lands and spell out actions that local self-government bodies could take to improve socioeconomic and infrastructure development in localities affected by gold mining. But no such agreement has been signed.

An identical situation with violation of FPIC principles occurred in Kemerovo Oblast, where territories of traditional nature use for small Indigenous peoples have not been formed at the level of federal constituent entity as they have been in the Republic of Khakassia, even though representatives of Indigenous communities have lobbied the government for this over the past five years.

Because they are not part of a territory of traditional nature use, the Shor villages of Orton, Trekhrechye, Uchas, and Ilinka, which have all been affected by gold mining, have been added to the Federal List of Places of Traditional Residence and Activities of Small Indigenous Peoples, approved by RF Government Resolution No. 631-r of August 5, 2009. In spite of these restrictions, in recent years the Subsoil Use Department for Siberia has issued at least three licenses for placer mining near Shor villages without holding any public hearings.

Traditional hunting

In addition to ambiguity surrounding land rights on territories of traditional residence, conflicts about hunting lands have arisen between the Shor and the gold-mining companies. On the one hand, Part 1 of Article 49 of Federal Law No. 52-FZ of April 24, 1995 “On Wildlife” envisages the right of people who are members of small Indigenous peoples of the Russian Federation to have preferential use of wildlife on territories of traditional settlement in places where these peoples have traditionally lived and conducted activities. On the other hand, Russian law places no restrictions on auctions and tenders for the right to lease forest areas and hunting lands in places where Indigenous peoples live, except when these territories are part of a territory of traditional nature use. This creates fertile ground for conflicts between Indigenous communities and private companies that have been granted the right to use these territories; it also creates the risk that hunting spots will be arbitrarily transferred to gold-mining companies. In recent years, the Kuzbass Forestry Department has started auctioning off the right to enter into agreements to lease agricultural and hunting lands where the Shor have practiced their trades for centuries. Private companies that have won the right to own and use a plot in an auction often restrict the rights of members of small Indigenous peoples by preventing them from hunting or even entering the territory. A ban like this is catastrophic for Shor living in remote areas of Mezhdurechensky Municipal District where there are no jobs or opportunities for earning a livelihood aside from traditional trades.

Local budgets receive almost nothing

One common argument in favor of the commercial exploitation of traditional Indigenous lands is that mining companies contribute to regional budgets and promote regional well-being and socioeconomic development. This, however, is misleading: While causing so much harm to the territories where the Shor traditionally reside, almost none of the abovementioned gold-mining companies are registered with the municipal districts where they process the subsoil. Of these companies, only two are registered where they operate – Izas, in Khakassia and Pay-Cher 2, in Kemerovo Oblast. All the other companies are registered in Krasnoyarsk Krai and pay taxes to the federal budget and the budget of the constituent entity where they are registered. Thus, the Shor, who are surrounded by gold-mining plots, do not receive any benefits from the mining companies.

The traditional territories where the Shor of Khakassia and Kemerovo Oblast live are nowhere near large localities. Most of them do not have stores, schools, medical facilities, or proper roads connecting these villages with district centers.

Most Shor settlements have no companies or institutions that could employ the local population. The unemployment rate in areas where the Shor traditionally reside is nearly 1.2 times higher than the average rate for the region: the unemployment rates in Askizsky District, Khakassia and in Tashtypsky district are 8.06 percent and 7.7 percent, respectively, which are the second and third highest rates in the region. In this situation, the only sources of cash income are agriculture and the products of traditional trades like hunting, fishing, and foraging. There are also fewer and fewer traditional economic activities that are viable because of the adverse impact of operations on the environment.

Hunting on traditional Shor lands is complicated not just by the worsening environmental situation, but by the fact that the mines simply do not allow hunters to access these places or threaten to do this, especially in relation to people who loudly protest against gold mining. Unfortunately, the mines have leverage: For example, one of the senior managers at the Pay-Cher 2 cooperative is both the lease holder of a forest plot and the owner of a private hunting business that borders Shor hunting grounds.

Residents of territories affected by the activities of gold-mining cooperatives have become hostage to this situation, but for Indigenous peoples it means not just the destruction of their customary environment, but also the loss of their identity, language, and culture. The fact that the Shor people are in a category of small Indigenous peoples under the special protection of Russian law should guarantee their development and well-being, but they are gradually losing their habitual places of residence, activities, and income because of gold- and coal-mining. This is a threat to their very existence.

Read more about the destruction of Shorian environment in the report

Feedback

Feedback