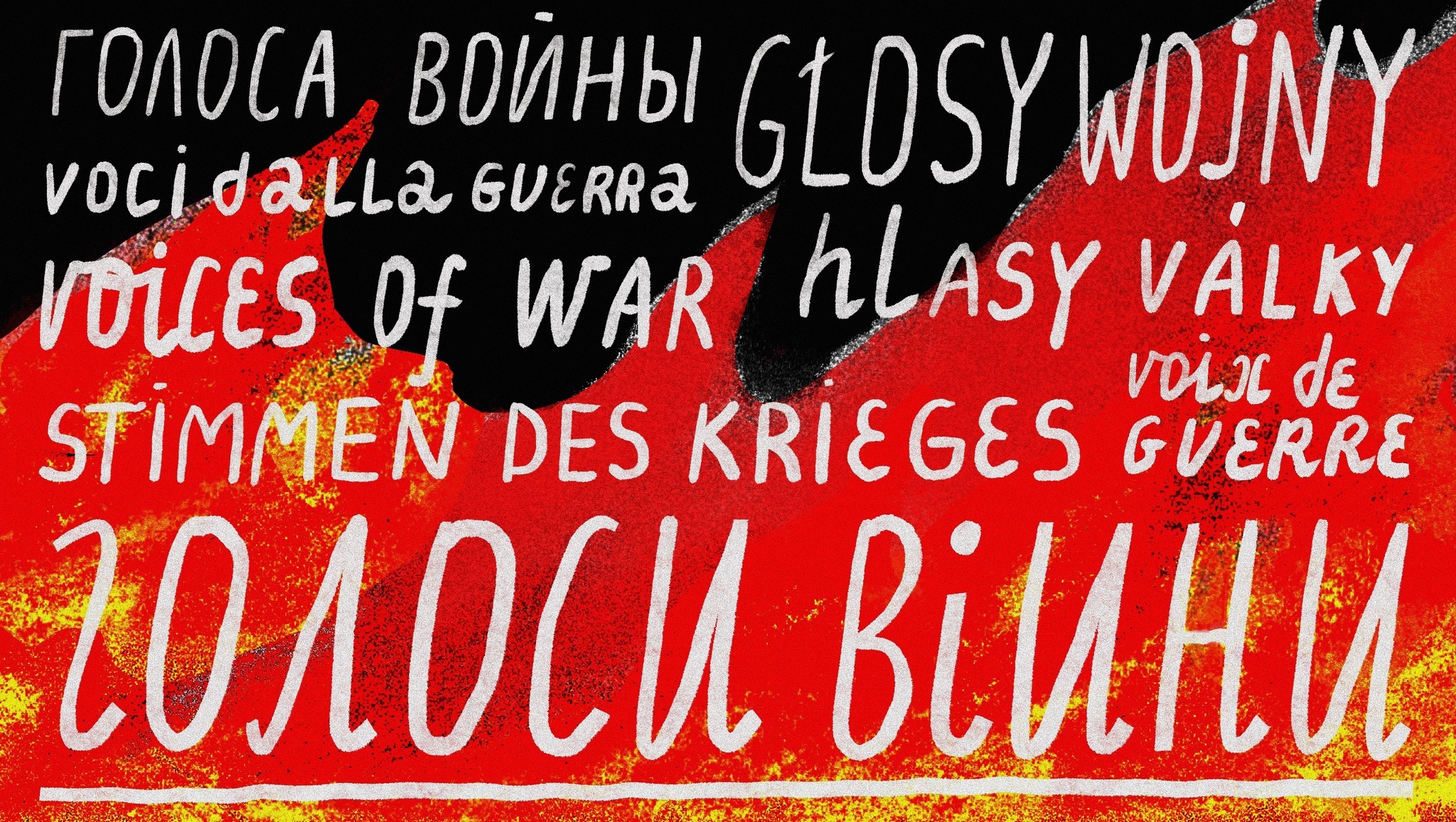

As part of the annual events dedicated to International Roma Day – 8 of April, a discussion took place in Brussels focusing on the participation of Roma in defending Ukraine against Russian aggression. The event was organized by ADC “Memorial” with the support of the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) and with the participation of the Ukrainian Center for Roma Studies of Kherson State University.

The main speakers of the meeting were Arsen Mednyk and Oleksii Panchenko — militaries who joined the army voluntarily, and representatives of Ukraine’s Roma community.

Since the very beginning of Russia’s aggression in 2014, thousands of Roma have been affected by the war: as civilians on temporarily occupied territories, as refugees trying to escape to safer areas, and as military personnel. Since February 2022, Ukrainian Roma have been sharing the hardships of war together with the other nationalities, defending their homes, families, and country on the frontline.

During the meeting, a documentary film was presented about the life of Arsen Mednyk — a veteran of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, who went through intense combat and suffered a serious injury. Despite the discrimination Arsen faced both before the war and at the beginning of his service, he became a commander of a storm-unit and shattered the stereotypes usually connected with Roma.

“I went to fight for my home, for my family. Later, I saw how the storm-teams worked — and I wanted to be one of them,” he said.

Another participant of the meeting, Oleksii Panchenko, emphasized:

“In battle, we are all equal — we drank from the same flask, shared a single can of stew among five people.”

Participants of the meeting in Brussels also discussed discrimination and crimes committed by Russian forces against the Roma population in the occupied territories of Ukraine (in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions): killings, rapes, abductions, and extortion. Yanush Panchenko, an expert and human rights defender, called for these cases to be documented and made public:

“Many Roma are afraid to tell these stories because they hope to return home. But silence does not protect. These stories must be heard.”

According to experts and media estimates, around a thousand Roma are serving in the Ukrainian Armed Forces in 2025. Their contribution is not only to the defense of the country but also to breaking down long-standing stereotypes. “Arsen, Oleksii, and other Roma who are fighting on the frontlines have done more in three years to combat discrimination and improve the image of Roma in Ukraine and Europe than anyone could have expected,” says Yanush Panchenko.

This publication contains three first-person testimonies:

- Arsen Mednyk, who went to the front after the occupation of his hometown Bucha and became a commander, breaking stereotypes about Roma in the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

- Oleksii Panchenko, a driver from Zaporizhzhya region, for whom the frontline became a place of equality and brotherhood.

- Yanush Panchenko, a human rights defender and researcher who documents the stories of Roma affected by the war.

Their stories are not only about war but also about dignity, solidarity, and the right to be part of their country’s history.

“I went to fight for my home.”

The story of Arsen Mednyk

My name is Arsen. I went to the front because my family was under occupation — in the town of Bucha. This is my hometown. My relatives, neighbors, and friends lived there — Ukrainians, with whom we were always close. I went to fight for my home and my family.

At first, I served in the Civil Defense in Kyiv region — in Bucha, Kyiv. The attitude toward me was initially distrustful. I am Roma, and I was not immediately accepted. But everything changed in the first battle. Then I showed that I could act decisively and be at the right place. My comrades and I survived, and after that, they began to treat me as an equal. I broke the stereotypes. They saw in me not a “Gypsy,” but a person.

Later, I saw how the storm-unit worked. So coordinated, like a single organism — I wanted to be part of such a team. By that time, my family was already safe, and I went to the military enlistment office and soon found myself at the training camp. Thanks to my experience and the support of a former commander, I quickly completed my training. There I received my nick-name — Baron. I had leadership skills, and I always spoke the truth, whether I was talking to a soldier or an officer.

I knew how hard it was for the officers of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and I respected them. They respected me as well. Once, there were large-caliber machine guns lying on the training ground, and no one knew how to set them up. I found a video on YouTube, studied it carefully, and set it up correctly on the first try. That earned respect, and people started to trust me.

Yes, I faced discrimination. One guy said: “Gypsies are fun people, but we don’t need them here.” But my comrades stopped him themselves. Without fights — they just explained. Since then — not a single word against me.

There was discrimination before the war, too. The police often stopped me — just because of my appearance. In the subway, in stores. I instinctively reached for my passport. When you live with this all the time — it weighs on you. But I went to the army not for those who discriminated against me. I went for the future. For the children. For the people.

When you know that your family could die, and you have a chance to protect them — you take up arms. That was my decision. And on the frontline, everything is different. There, it doesn’t matter who you are. What matters is how you act. I became a commander after our commander was killed. The guys themselves said: “You’re the commander. You weren’t afraid, you went forward. It’s safe for us to follow you.”

But there were also terrible moments. One of them was the death of my friend Yura. He was only 22 years old. A tank shell pierced a tree, his bulletproof vest, and his body. He died right in front of my eyes — it was like losing a brother. He had no wife, no children, he was the last in his family line — it is genocide. And I will never forget this.

After I was wounded — shrapnel in my arm, loss of hearing, pain — an inner war began. Insomnia, memories, guilt for surviving. Only a conversation with a psychologist helped me begin to get out of it. Now, every day feels like a battle. But I hold on.

In the future, I want to return to my craft. I am a shoe repairman, a jeweler. I will work. And of course, I see my future only with Ukraine. This is my home.

Since 2014, the situation in the country has started to change. There was less lawlessness, less discrimination. And since 2022, people began helping each other. The main thing is to survive. And I see how attitudes towards Roma are changing. I told people: “You know me, I have never done anything bad to you — why do you judge me because of my ethnicity?” Sometimes it worked.

I believe that our contribution, the contribution of Roma on the frontlines, would change attitudes towards us. We are defending Ukraine. And I want us to be respected for this. Even a simple “thank you” is important. It helps to believe that we did not fight in vain.

Roma on the Frontline Is Not a Sensation, but a Reality

The story of Oleksii Panchenko: volunteer, driver, soldier

My name is Oleksii. I am Rom, originally from the Zaporizhzhya region. Before the war, I worked all over Europe — as a truck driver, a mechanic. When the full-scale invasion began, I left the occupied territory on April 8. With us were a woman and three children. By April 15, I was already at the military enlistment office. I came there voluntarily, I accepted it as the only possible decision.

I served as a convoy driver, operating a large vehicle. We were often sent on evacuations, transportation missions. I was rarely stationed in one place, always on the move. It was hard, but it was important for me to be in the right place and to do everything I could.

Honestly, no one initially knew I’m a Rom — they didn’t ask. Later, maybe they guessed — but no one said anything. Not in my unit, not in the battalion. When it eventually became known that I am a Rom, people were surprised. They even came over from other battalions — as if on an excursion.

But on the frontlines, everyone is equal. There, it doesn’t matter who you are by nationality. In the trench, in the forest, while driving — everyone shares one can of stew, drinks water from the same bottle. I didn’t feel any discrimination. We were a real team.

The warmest moment of my service was my birthday. We were on high alert, under threat. The guys went to the store, brought back a big cake, and two bottles of champagne. I was asleep in the KAMAZ truck. And when I woke up, there was the cake, my friends next to me, all alive. That was the best gift. Because there was death all around. Too much death — I don’t even want to say how much. But that day, I will remember it forever.

My family still lives in the occupied territory. We constantly worry about them. When we were traveling through Vasylivka, a Chechen soldier stopped us at a checkpoint. He said, “Stay here — it will be fun.” But I replied: “No, I’ll go further.” They checked us, looked at our documents, and we got through. There were many checkpoints, but we were lucky.

I didn’t face discrimination personally, but I know it exists. I always tried to be dignified, to do my job conscientiously. And maybe that was felt. I had comrades who valued actions, not origins. We became true brothers.

In war, this is felt even more acutely — your life depends on the other person. And their life depends on you. There, everything is laid bare. Real values, spirit, determination. And nationality doesn’t matter anymore.

Roma on the Frontline: We Are Fighting for Ukraine

The story of Yanush Panchenko — human rights defender, researcher, and co-founder of the Ukrainian Center for Roma Studies at Kherson State University

I am Roma, and I have dedicated most of my life to working with the Roma community — as an activist, researcher, and human rights defender. I know how discrimination works from the inside — not only because I have experienced it myself but also because I listen to the stories of others. People like Arsen and Oleksii.

When I entered university in Kyiv, my family told me: “You’re going to live among non-Roma — don’t tell anyone you’re Roma.” For a long time, I remained silent among students and new acquaintances. But one day I realized: hiding yourself means agreeing with other people’s prejudices. I started to speak openly about my identity — and I saw that it changed attitudes. The professors began to take an interest, to show respect. I realized I could not only speak — I could represent our community.

Today, I work with those affected by the war — including Roma. I know of cases where Roma were abducted, tortured, held in captivity. A boy with a disability, a teenager, was taken to prison in Kakhovka. They forced him to dig, to bury bodies. A woman had to ransom her own son from the soldiers. My brother was detained because of messages found on his phone. These stories are an everyday tragedy that people are often afraid to talk about.

Roma remain silent — out of fear of losing their homes, the possibility of returning, or simply out of a habit of keeping to themselves. But we must speak out. Because the contribution of Roma to this war is enormous. In the first years alone, around a thousand Roma served in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. They have done more to break stereotypes than dozens of roundtables.

Remember in 2022, when Roma captured a tank in Lyubymivka? It became a meme — and at the same time, a real symbol. Our research showed that 55% of Ukrainians know about it, and many of them changed their attitudes toward Roma. That is the power of a real story.

But everything depends on whether these stories will be told. Will they be heard? Will they become part of Ukraine’s history? These people have already done their part — they lost their health, and some lost their lives. Their input is no less than anyone else’s.

I dream that after victory, Roma will be visible — in schools, in museums, on the streets, in parliament. Because they are already on the frontlines. And they are fighting for Ukraine.

Photos are courtesy of Yanush Panchenko

Feedback

Feedback