In recent years, after the invasion of Ukraine, Russia has significantly tightened its legislation on migration and citizenship, and some innovations create an immediate risk of statelessness.

The long-standing problem of statelessness has not yet been solved in Russia, while it is rooted in the 30 years ago events of the collapse of the USSR and related changes of the borders and the emerging sovereignty of post-Soviet countries. In April 2023, a new version of the Law on Citizenship of the Russian Federation was adopted (entered into force in October 2024). According to authoritative experts, the consequences of the law in its current form will be ambiguous: some groups of stateless persons have retained or received preferences in access to Russian citizenship, while others have lost their existing advantages, and it is not possible to understand the logic of legislators. Thus, the most vulnerable stateless persons are citizens of the former USSR without valid documents, whose problems were addressed in a separate chapter VIII.1 in the old version of the law, in the new version they were deprived of their former and at least theoretical benefits (the “simplified procedure” for obtaining citizenship); now they can only follow the long and thorny path of the “general procedure” for applying for citizenship. Elena Burtina, expert of the Civil Assistance Committee, concludes that “the balance of gains and losses is definitely leaning towards the latter, since the bulk of stateless citizens of the former USSR are de facto deprived of the prospects of obtaining citizenship.”

Innovations related to the deprivation of acquired citizenship definitely have negative consequences. Article 22 of the Law on Citizenship in the 2017 version, “Grounds for the cancellation of decisions on citizenship of the Russian Federation”, has already caused human rights defenders to sound the alarm. It states that acquired citizenship can be taken away if the applicant has provided false information / forged documents (Part 1 of Article 22); crimes committed under a number of articles (related to “terrorist” and “extremist” matters), and addressed with a sentence that has entered into force (part 2 of Article 22), are equated to providing false information /forged documents.

In 2021, the legitimacy of Part 2 of Article 22 was considered by the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation, and, unfortunately, the Court did not see legal uncertainty in it. Just to remind: the request was initiated by the Supreme Court of Karelia in connection with a high-profile case of Alexei Novikov, who was deprived of his only Russian citizenship (the reason for the stripping citizenship was a conviction under a “terrorist” article, although Novikov declared a forced confession of guilt under torture at the trial). The Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation was not confused by the fact that a considerable time had passed between obtaining citizenship (2005) and the verdict (2017).

In the already mentioned new version of the Law on Citizenship of the Russian Federation (April 2023, entered into force at the end of October 2023), Chapter 4 “Cancellation of decisions on citizenship of the Russian Federation” is significantly expanded. Now the grounds for deprivation of citizenship are formulated as follows (Article 22):

2) the communication of deliberately false information regarding the obligation to comply with the Constitution of the Russian Federation and the legislation of the Russian Federation, expressed in particular:

a) in the commission of a crime (preparation for a crime or attempted crime);

b) in committing actions that pose a threat to the national security of the Russian Federation;

c) failure to fulfill the obligation to initially register for military service (this paragraph was added in the wording of Federal Law No. 281-FZ dated 08.08.2024).

3) submission of forged or invalid documents or reported knowingly false information on the basis of which a decision was made on admission to citizenship of the Russian Federation or a decision on recognition as a citizen of the Russian Federation;

4) other grounds provided for by an international treaty of the Russian Federation providing an opportunity to retain or change citizenship.

The other articles of the Law specify the list of articles of the Criminal Code, that, with the related sentences, serve as the basis for deprivation of citizenship (articles of these 64); it is indicated that the decision to deprive citizenship is made regardless of the time of the crime, the date of the court verdict and the date of the decision on admission to citizenship of the Russian Federation (Article 24), that may cover the expunged criminal record. Article 25 speaks about such grounds for deprivation of citizenship as “committing actions that pose a threat to the national security of the Russian Federation.” The fact of committing these actions, which are not specified in any way, should be registered by the FSB authorities; the time period for detecting this fact and the time for committing actions to make a decision on deprivation of citizenship also does not matter, as in the case of a crime. In this formulation, the law provides the widest field for arbitrary and illegal decisions.

In the first six months of the new version of the Law on Citizenship of the Russian Federation, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia terminated the acquired Russian citizenship of 398 people because of the crimes they committed (response of the Ministry of Internal Affairs to a request from TASS, April 2024). In the period from January to July 2024, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia deprived about 1000 people of citizenship for the same reason (message from an official representative Ministry of Internal Affairs, July 31, 2024).

Citizenship in a war situation is an instrument of blackmail and intimidation

Russia’s migration policy in recent decades has been cynical and controversial. On one hand, the country is experiencing a shortage of labor resources, and entire employment sectors (construction, transport, utilities) were mainly occupied by migrants. Migrant labor brings emormous profits to the Russian economy, including the money that migrants pay, officially and in the form of bribes, for documents, registration, and the right to work etc. The lack of a transparent system for legalizing migrants in Russia is partly explained by the multilevel corruption that has grown over labor migration.

On the other hand, the Russian authorities seek to limit migration, condone manifestations of racism, often support xenophobes and initiate anti-migrant actions themselves. Law enforcement agencies are willing to involve activists of nationalist movements (like the recently emerged “Russian Community”) in anti-migrant raids. The migration legislation of the Russian Federation is being tightened all the time: in the regions, migrants are prohibited from working in certain areas (transport, education, healthcare); Migrant children are being restricted in their right to education (a bill is being prepared to ban their admission to school without confirming their competence in the Russian language); a special regime for the expulsion of migrant has been introduced, significantly restricting their rights.

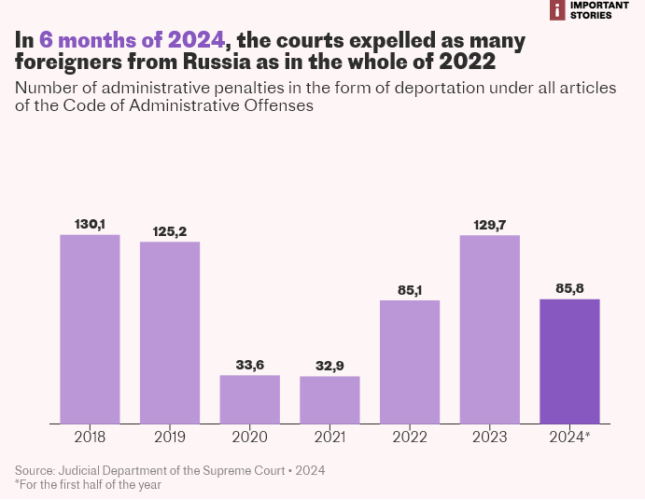

In the first half of 2024, the courts decided to expel about 86 000 foreigners from Russia, 124 000 administrative cases of violation of migration rules were submitted to the courts – which is close to the data for the whole 12 months of 2022; (data from the Judicial Department at the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation, “Important Stories“, October 21, 2024).

https://istories.media/en/news/2024/10/21/judges-versus-migrants/

Why, despite all the risks, do migrants continue to go to work in Russia and seek to obtain Russian citizenship? Inter alia, in order to avoid bureaucratic procedures of registration, obtaining a patent, etc. and related costs. Probably the main motivation is the need to look for sufficient income in a more economically developed country to support a family. There are other motives: for example, for representatives of vulnerable minorities, labor migration to Russia is often the only way to avoid physical danger and repression in the country of origin (this is how Uzbeks from Southern Kyrgyzstan or Pamiris from Tajikistan used to emigrate). However, after the beginning of Russia’s invasion in Ukraine, many of the naturalized citizens of the Russian Federation – recent migrant workers regretted that they acquired Russian citizenship: instead of protection, it promises them the risk to be killed at the war.

Such grounds for deprivation of citizenship as the separately stipulated “non-registration for military service”, as well as some other violations of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation – “desertion”, “voluntary surrender”, “discrediting the army”, are obviously related to the war that Russia is waging against Ukraine. These repressive norms are directed against anti–war-minded naturalized citizens and aim, on the one hand, to drive recent migrants (and now Russian citizens), into the Russian army, and on the other hand, to suppress all dissent and prevent anti-war protest.

One of the most rabid mouthpieces of anti–migrant rhetoric in the highest echelons of the Russian authorities is the head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, Alexander Bastrykin. Manipulating statistics on crime among migrants in his manner (by the way, the data disputed by another department – the Ministry of Internal Affairs), he lobbies to limit the number of migrants, often calling already naturalized citizens of the Russian Federation “migrants”. In recent years, he sees sending immigrants from other countries to war as a means of such restriction. In January 2023, Bastrykin stated that participation in the military actions for naturalized foreigners was their constitutional duty and that it was necessary to consider sending them to the front as a priority. At the legal forum in St. Petersburg (summer 2024), Bastrykin proudly said that through the efforts of his unit, about 10,000 naturalized citizens joined the Russian army, and those who did not want to serve in the army left Russia.

The recruitment of recent migrants with acquired Russian citizenship began immediately after the outbreak of the war. Foreigners who have received Russian citizenship are required to serve in the Russian armed forces, even if they have already served in their native countries. The only exceptions are citizens of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, as Russia has signed relevant agreements with these countries.

After the outbreak of war, representatives of the Ministry of Defense began calling natives of Central Asia with Russian citizenship, both young and older than military age, threatening to take away their acquired citizenship in case of evasion from service.

Those who were just planning to obtain Russian citizenship were also lured into the army. Back in December 2021, President Putin introduced a bill to the State Duma that simplified obtaining Russian citizenship for military personnel under contract in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. Even before the official adoption of the law (September 2022), recruiters promised migrants citizenship within three months after signing the contract. Representatives of the Ministry of Defense placed advertisements in Russia and Central Asian countries, promising salaries of up to 200 000 rubles per month (almost $3,000). The private military company Wagner also conducted a recruiting campaign on social networks in Central Asia.

Not only recent citizens of the Russian Federation are forced to serve in the Russian army, but also migrants serving sentences in Russian prisons. At the same time, foreign prisoners report that they are being persuaded to deny the citizenship of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, apply for Russian citizenship and sign a contract with the Russian army (appeal of prisoners from a colony near Moscow, a publication of “Current Time”, October 14, 2024).

After the mobilization was announced (autumn 2022), media reports appeared that migrants from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan working in the Russian Federation began to receive summonses, despite the fact that they did not have Russian citizenship. And the Moscow authorities have opened a recruitment center on the basis of the Sakharovo migration center.

At the beginning of 2023, cases of bans on leaving the Russian Federation for natives of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan with Russian passports became known. They were informed that they were on the mobilization lists and for this reason could not leave the territory of Russia.

Gains and losses in the struggle for the rights of stateless persons and migrants

Against the background of the war, anti-migrant hysteria, stricter migration legislation, the adoption and application of laws that directly lead to statelessness, Russia risks losing the achievements that defenders of the rights of stateless persons and migrants have been seeking for so long. In general, we are talking about the implementation of the strategic decision of the European Court of Human Rights in the case “Kim v. Russia”, which took almost 10 years.

Just to remind the case of Roman Kim (2014) – a stateless person, an ethnic Korean, a native of Uzbekistan (Koreans were repressed as a people and in 1937 were subjected to mass deportation to the Soviet republics of Central Asia). The Russian court recognized Kim as a violator of migration legislation, ordered him to be expelled, and in order to ensure his expulsion, he was detained (in fact for indefinite period of time, since the expulsion of stateless persons is impossible) in a detention center for foreigners and stateless persons, where he spent more than two years (longer than even the law allowed). The ECHR considered this a violation of a number of articles of the European Convention and, in addition to individual measures (monetary compensation for the difficult conditions of detention in the center for foreigners), ordered Russia to take general measures so that expulsion would not be applied to stateless persons, so that judicial control over the legality and duration of detention in deportation centers would be introduced, and this period itself is limited to ensure that stateless persons receive documents allowing them to legally live and work in the Russian Federation.

The Russian government has long sabotaged the implementation of the ECHR decision in the Kim case – it took a lot of work by lawyers and human rights defenders, filing similar cases in the ECHR and the strategic case of Noe Mskhiladze in the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation (2017). The procedure for the legalization of stateless persons started working only in 2021. The Law on the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens in the Russian Federation and other legislative acts were amended (Law No. 22-FZ of February 24, 2021, entered into force 180 days later in August 2021). Now stateless persons can obtain an identity card for 10 years for a limited time, legally live and work in Russia (Article 52 of the Law on the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens).

Judicial control over the reasons and terms of detention in centers for foreigners was introduced even later – at the very end of 2023, already in the midst of the war unleashed by Russia against Ukraine. It concerns not only stateless persons, but also migrants with citizenship of other countries, that is, a much wider range of people, including Ukrainians, who cannot return to their homeland due to the war and closed borders. The Administrative Code (amendments, Federal Law No. 649-FZ as of 25/12/2023) finally introduced a rule on limiting detention in the Central Prison for a period of no more than 90 days and judicial control over the extension of this period (no more than 90 days) if the Interior Ministry authorities applied for an extension in a timely manner. In their turn, the migrant detainees can apply for expulsion at their own expense – and the court is obliged to consider such a request within 5 days. Even more importantly, the law explicitly points to the right of people placed in the detention centers to apply to the court to verify the legality of their deprivation of liberty “in the presence of circumstances indicating the absence of an actual possibility of expulsion from the Russian Federation.”

However, another tightening of migration legislation in matters of expulsion has significantly expanded the powers of the police. If so far only the court has taken decisions on expulsion, then amendments to the Administrative Code (Federal Law No. 248-FZ of August 8, 2023, will enter into force in January 2025) have given the Interior Ministry (police) the right to make such decisions. It can be predicted that their appeal to the courts (according to the law, possible within 10 days after receiving of the decisions) will be difficult: the expulsion order may be executed immediately, the foreigner may simply not have the opportunity to go to court.

Olga ABRAMENKO, expert, ADC Memorial

Feedback

Feedback