Anti-Discrimination Centre Memorial Brussels publishes the 3rd report on the situation of children from Ukraine during the 2022-2023 war, the results of monitoring the situation as part of the #crossborderchildhoodua campaign with the support of the Fondation de France.

ADC Memorial thanks the colleagues who carried out monitoring of the situation of Ukrainian children in Europe:

Yevheniia Lutsenko (Belgium)

Katerina Nazarshoeva (Germany)

Riccardo Nicosia (Italy)

Oksana Maslova (Czech Republic)

Elena Plotnikova (Lithuania, Latvia)

Larysa Klopova (Switzerland)

AVE Copiii (Moldova)

Ana Riaboshenko (Georgia)

ADC Memorial expresses its special thanks to Tatiana Bondar for the analysis of the monitoring data and preparation of the text of the report.

The presentation of the report will take place in Brussels on 20 June.

Introduction

Russia’s military invasion and the intense fighting that has continued in Ukraine since 24 February 2022 have caused the mass displacement of the civilian population within Ukraine and beyond in numbers unprecedented in modern European history.

Over 1.5 million people left Ukraine at the very beginning of the war – from 27 February 2022 to 9 March 2022, over 150,000 people left the country every day. On 6 March 2022, a historic high of 210,500 people were recorded crossing the border. Since 24 February 2022, approximately one-third of all Ukrainians, including children, have been forced to flee their homes. According to data that is regularly updated by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, as of 9 May 2023, 8,207,977 Ukrainian refugees were in Europe. Of these, 5,093,606 had registered for temporary protections and similar national protection mechanisms. In addition, the UNHCR has recorded 2,875,215 refugees in the aggressor countries of Russia and its satellite, Belarus. As of 23 January 2023, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) put the number of internally-displaced people in Ukraine at 5,352,000.

There are no exact figures on the number of Ukrainian children abroad because of the constantly changing situation and differing approaches to calculations, among other things. Various analytical systems put the percentage of children among refugees at 34%-40%, which means that almost 3 million children and young people have left Ukraine since the beginning of the Russian invasion. In the summer of 2022, 672,000 Ukrainian schoolchildren were in different countries (interview with Ruslan Gurak, the head of the Ukrainian State Service of Education Quality, 21 July 2022); 185,000 Ukrainian children started the 2022-2023 academic year in Polish schools (interview with Polish Education Minister, 2 September 2022).

Countries throughout Europe and the world have shown unprecedented solidarity with Ukrainian refugees. This involves both general institutional measures of support at international and country levels and the mobilization of nongovernmental organizations, volunteer activists, and concerned citizens.

This report is based on data from monitoring studies and surveys of dozens of parents and children from refugee families, as well as officials, NGO staff, volunteers, and other people involved in helping Ukrainian refugees. The monitoring studies were conducted from October 2022 through March 2023 both remotely and in person in Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Switzerland, Norway, and EU countries (Poland, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Belgium). Many people questioned represent groups with certain vulnerabilities, including families with many children, families with children with disabilities, and Romani families. The report also cites other studies on similar topics and data from other open sources.

This report does not claim to be a comprehensive study of emigration by Ukrainians caused by the war. The situation is changing quite rapidly in terms of statistics, refugee movement between countries, their return to Ukraine, success integrating into new communities, and the creation of opportunities for them abroad. The survey was conducted of people who have been traumatized by the war and suffered the loss of loved ones, shelling, life in shelters, the tragic experience of evacuation and crossing the border, and adaptation to the difficulties of life in other countries. All of this left a distinct impression on their responses, their willingness to speak openly, and their assessments of their situation. The monitoring studies were not conducted in every country that hosts Ukrainians. However, this data helps identify important problems related to refugee integration, best practices, and questionable decisions made by host countries. This report is also important as a document of the times that records the words, opinions, and moods of children and adults suffering from the war.

The problems associated with observance of the rights of children who left their communities in Ukraine falls under the purview of a wide range of institutions in dozens of countries; there are no simple or ready solutions during wartime and in the face of a complex migration crisis. Therefore, the authors of this report are first and foremost attempting to define problems, both obvious ones and ones that may not have been given enough attention yet.

Summary: main problems identified during monitoring of the situation of Ukrainian children in European countries

- Incomplete statistical and other information about children, including unaccompanied children, who left Ukraine; insufficient awareness of Ukrainian children’s protection services concerning the situation of children abroad; poor cooperation between children’s protection services abroad and in Ukraine. This problem could be resolved by bilateral agreements between Ukraine and other countries similar to Ukraine’s existing intergovernmental agreements with Poland and Lithuania.

- Difficulties encountered by Ukrainian residents of temporarily occupied territories and/or frontline territories entering the EU caused by the lack of recognition of documents they were forced to obtain (passports of the so-called “DPR” and “LPR,” Russian birth certificates, and so forth); arbitrary decisions by border guards on allowing into the EU people who spent a significant amount of time in Russia.

- Discrimination of Romani refugees caused by both xenophobia and systemic problems typical for this group (problems with documents, poor integration, low level of education). Romani people from Ukraine experience difficulties crossing the border and discrimination when seeking accommodation in refugee centers and, later, housing; attempting to receive humanitarian aid; and attempting to enroll their children in school. Difficulties with integration force Romani families to seek better conditions, which means their children fall out of the education system and they experience deintegration.

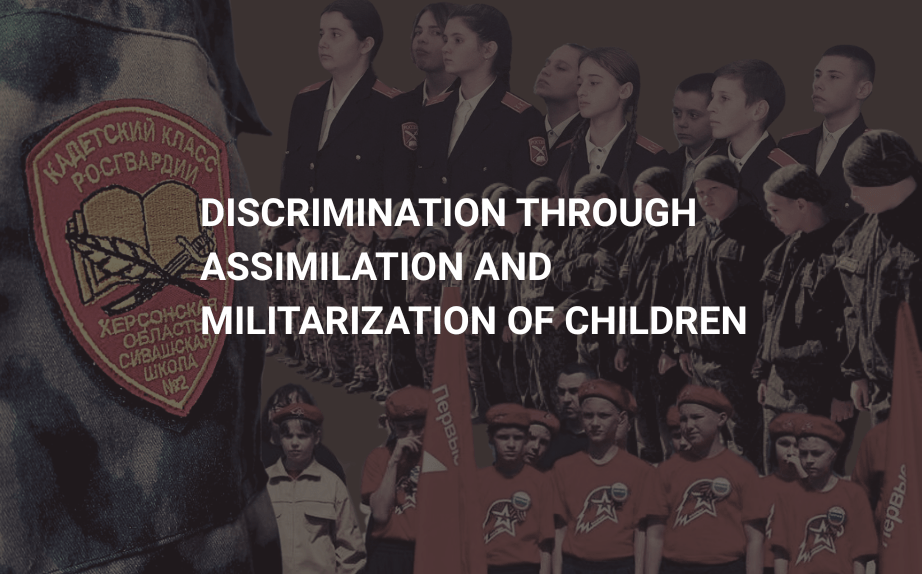

- The war has stalled the deinstitutionalization of Ukraine’s children’s institutions. Europe has taken various approaches to accommodating children’s homes that were evacuated in an organized manner. These have including retaining the existing structures of the Ukrainian institutions, dissolving them, not recognizing the rights of the directors of these institutions, and appointing local guardians in the host countries. Children and staff members at children’s homes were not prepared for this form of accommodation.

- Ukrainian parents are often poorly informed of their children’s rights and the need for strict compliance with them, in particular the unacceptability of physical punishment and other aggressive disciplinary tactics. Ignorance of these rules results in punitive sanctions and even the removal of children from parents in European countries, which has a traumatic effect on children.

- Even though European countries have made significant efforts to integrate Ukrainian children into school environments and Ukrainian schools have continued to provide remote instruction for children who left the country, many children are at risk of falling out of the education system, are not receiving instruction that matches their age, are losing one or even two years of schooling, and are under tremendous stress (they have to learn in their non-native languages, take promotion and graduation exams, and maintain a double school load – in their countries of emigration and online in Ukraine). This situation is particularly hard on Romani children, who are traditionally vulnerable within the education system.

- While refugee children in European countries are largely covered by medical care within the framework of national healthcare systems and volunteer initiatives, the situation is worse with psychological care, which almost every child who has experienced war and emigration needs. This is due not only to the language barrier and the lack of staff and resources, but also to continuing distrust in this type of support, stigmatization, and the absence of a culture of seeking psychological care.

1. Evacuation, border crossing, and accommodations for children from several vulnerable groups

Readiness for emigration, urgency of the decision to move, and choice of country obviously differed for families depending on their initial situations and factors like experience with labor migration; level of education and qualifications making it possible to find work in another country; the presence of relatives or friends or an active Ukrainian diaspora abroad; the host country’s geographical, cultural, and linguistic proximity to Ukraine; refugee support programs in the country of emigration; and so forth.

Parents often made the decision to leave and move to a different country without any input from their children, who were simply informed of the adults’ decision on the need to evacuate.

“Nastya’s a child. What’s there to discuss with her?”

Vitaly, immigrant, father of a 13-year-old daughter.

The study “Ukrainian refugees: who are they, where did they come from and how to return them” (Centre for Economic Strategy, 22 February 2023) shows that a relatively high share of refugees (almost 58% of the sample) are made up of people who are well-adapted to emigration: people who had a propensity for labor migration before the war, as well as highly qualified professionals with average to high incomes before the war. The so-called “classic refugees” are much more vulnerable. These include poor, middle-aged women with children (almost 25% of the sample) choosing geographically close countries (Poland, Czech Republic) and large cities who emigrated during the initial period of the war from territories where there were no active hostilities. Another vulnerable group (almost 16%) were refugees from territories seeing hostilities. These refugees suffered most from the war and often had nowhere to return to. They emigrated in a later period and chose countries with good benefits and assistance programs (for example, Germany).

Some countries turned out to be transit countries. For example, the first wave of refugees in Georgia was made up of Ukrainian tourists who were there for the ski season when the war started. Over time, most of them moved to European countries or returned to Ukraine. The second stream of migrants was made up of residents from occupied regions (Mariupol, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, and others). This group was mainly made up of people suffering from the hostilities, so they were worse off financially than the first stream. These were mainly women and children, the absolute majority of whom arrived in Georgia via Russia. After solving problems with documents, many of these people aimed to leave for Canada (through the large Ukrainian diaspora in that country) or European countries with robust programs for helping Ukrainian refugees.

The Baltic countries were also transit countries to a certain degree. Refugees, generally residents of occupied territories, end up there via Russia and continued on into Europe. In Latvia, the state does not envisage any aid system for transit refugees who do not plan to live there. It does not offer places for rest or overnight stays, food, or any other infrastructure. Families arriving at the train station in Riga simply wait there for the next train. Many arrive without money or suitable clothing and do not know anyone in the country. Assistance for such people is only provided by volunteers and concerned citizens (report, June 2022).

In the EU, most Ukrainians have the right to receive temporary protected status (for a year with the possibility of extension), which most refugees have taken advantage of. Even though this status provides the right to reside, work, and receive an education and medical care, living conditions for Ukrainians vary widely from country to country in the EU, since some countries, like Germany and Belgium, provide significant social payments, while others provide low payments, if any. In addition, Ukrainian citizens can spend up to 90 days out of a 180-day period visa-free in the EU, and they can also apply for asylum. In other European countries that are not part of the EU, Ukrainians have similar measures of temporary protection and asylum.

In this section, we will not describe in detail the tragic circumstances of evacuation for Ukrainian refugees, the circumstance of their protracted and often agonizing paths to safe countries, or the assistance they received from volunteers, nongovernmental and humanitarian organizations, or concerned people. Instead, we will focus on the problems of several vulnerable groups in emigration. These include children in institutions, unaccompanied children, and Romani children.

1.1 Unique features of emigration for children in institutions and unaccompanied children, problems with registration, approaches to settling them in European countries

In June 2022, the European Commission put the number of unaccompanied/separated children from Ukraine in EC countries at almost 23,000, noting that this figure was based only on partial data from countries and assuming that the actual number of such children in the EC was probably much higher (The EC Staff Working Document “Supporting the inclusion of displaced children from Ukraine in education: Considerations, key principles and practices for the school year 2022-2023”, 30.06.2022).

Ukrainian human rights organizations have noted with concern the lack of accurate information about unaccompanied children abroad and discrepancies with their records in Ukraine and have notified international bodies about this. After reviewing Ukraine’s state report at its 91st session in August 2022, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child recommended working with receiving countries to step up measures to identify and register more unaccompanied or separated children fleeing the armed conflict for the purpose of family reunification.

Recognizing the acute need to share data on people emigrating abroad with children, the Ukrainian Ministry of Social Policy sent a proposal to 23 EU countries to enter into intergovernmental agreements about monitoring the situation of Ukrainian children abroad and sharing information, including children’s information. For now, only two such agreements have been signed – with Poland and Lithuania.

A separate problem is the difference in Ukrainian and European border crossing laws as they concern older adolescents aged 16 to 18. Ukraine’s border crossing rules for Ukrainian citizens allow children this age to cross the border alone without an authorized adult and without being temporarily listed in consular registers at Ukraine’s diplomatic representative offices abroad. This means that Ukraine does not collect information about the number of unaccompanied 16-18 year olds who leave Ukraine and does not know where they are living or the terms of their residence abroad. However, Germany, Poland, and Italy have the practice of detaining unaccompanied 16-18 year olds and placing them in specialized institutions for unaccompanied adolescents (coalition report of Ukrainian NGOs for the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2022).

1.1.1 Institutional vs. family placement

The de-institutionalization of children’s institutions in Ukraine has been significantly complicated by the war and forced mass migration. Ukrainian children’s rights defenders have called for it to continue in wartime, and the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child also recommended this in 2022. Our monitoring study showed that European countries have different approaches to housing children evacuated in an organized manner as part of children’s institutions.

Within the framework of governmental agreements between Ukraine and Lithuania, several groups of children from Ukrainian children’s homes and the children of staff members at Ukrainian state institutions were evacuated to Lithuania in the spring of 2022. Upon their arrival, they were placed in specialized camps prepared by Lithuania with the same groups they arrived in the country with. Even though this procedure was introduced to protect children from illegal adoption, Lithuania also pointed to possible negative consequences for children from not being placed with families, where children who have suffered difficult, traumatic events would be more comfortable from a psychological standpoint. Lithuania aims insofar as possible to follow a policy of de-institutionalization: The country does not have children’s homes, and children are generally assigned to families or live in small groups (about 10 people) in “family homes” with “professional parents.” Registration of people who wanted to become temporary guardians of children from Ukraine had already been suspended by March 2022; by that time, over 900 applications had been received from potential foster families. Naturally, this isn’t about the applications, the majority of which would not have been approved, but it illustrates that it would have been potentially possible to move a fairly large number of children into the families of potential guardians. As of now, most of these children have left Lithuania.

As of 17 March 2023, 445 Ukrainian children who arrived in the country without parents were under provisional guardianship. The Orphans’ and Custody Court (there is one such court in every municipality) handles temporary guardianship and further monitoring of a child’s safety and well-being; it is overseen by the State Inspectorate for Protection of Childrens’ Rights. The court checked the Ukrainian citizens the child arrived with (relatives, acquaintances, trainers, teachers, and so forth) as candidates for guardianship; Latvian citizens had to go through a special procedure for this role. The court could also appoint a guardian if the child did not have identity documents or if the documents were issued within occupied territories of Ukraine, for example, Donetsk or Luhansk oblasts, and were therefore not recognized by the European Union. The Latvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has released guidelines for these cases and recommended that the relevant Latvian agencies use other documents to establish a blood relationship or, if this isn’t possible, ask a court to recognize a blood relationship on the basis of the unrecognized documents. The need to prove a blood relationship through a complicated procedure puts families under additional stress.

Our study identified cases where, because of differences from the Ukrainian understanding of the unaccompanied child status, children from children’s homes that were evacuated in an organized manner were deemed unaccompanied children, even though in Ukraine these children’s official guardians were the directors/staff of the children’s institutions. For example, in accordance with the understanding that de-institutionalization is the best practice for orphaned children in Italy, children from Ukrainian children’s homes were not placed together. Instead, one of two children were placed with Italian foster families. These families, however, were not prepared for long-term guardianship and the children were later moved to Italian institutions. This situation was unexpected and traumatic for both children and staff members, who were forced to deal with the unfamiliar Italian judicial system for children’s affairs.

The director of a children’s home that was evacuated to Italy on 17 March 2022 reported that her right to act as guardian for 24 children was not officially recognized in Italy. When they were being evacuated, the children were accompanied by four staff members from the children’s home, two of whom then returned to Ukraine. One to two children were placed with Italian foster families, while the director lived with four of the children. After one and a half months, a number of the families refused to continue serving as guardians for the Ukrainian children, so nine of them ended up in an Italian children’s institution. The director spent a lot of time in courts, fighting for her right to serve as guardian for the children. (Interview with ADC Memorial, summer 2022, Italy).

It was reported that in April 2022, 63 orphaned children arrived in Sicily on a special flight. Under a Juvenile Court decision, they were appointed Italian guardians and placed in small family-type children’s homes in different localities in Sicily.

However, the practice of de-institutionalizing children from Ukrainian children’s homes is not ubiquitous in Italy. For example, with assistance from the Ukrainian association Zlagoda in Bergamo, the small commune Rota d’Imagna, which is outside Milan, received an entire children’s home from Berdyansk, where 93 children aged eight to 18 were being raised as of late December 2022. This was an exception for Italy – family-type children’s homes generally do not accept more than 10 children. With the agreement of Prefecture Bergamo, a juvenile court in Brescia issued a decision that this arrangement was preferable for the children. This children’s home arrived in Italy via Poland. This was already its second move: In 2014, it was moved to Berdyansk from Donetsk Oblast. (L’orfanotrofio ucraino che ha cambiato un paese delle valli bergamasche, 25.12.2022, ilPost).

There have been cases where juvenile courts found that the director of a Ukrainian family-type children’s home had the right to custody. One example of this was the decision of a Bolzano court in relation to seven children from a children’s home that was evacuated as a group in April 2022. The court specified that minor citizens of Ukraine who are accompanied not by a parent, but by another “family member” cannot automatically be classified as minor unaccompanied foreigners.

On 13 April 2022, the Italian minister of foreign affairs made a statement on this matter in Italy’s Chamber of Deputies: “Since many minor Ukrainians arrive in Italy with a person who is not their parent and who cannot be classified as an accompanying person or legally responsible subject within the framework of our legal system, I can guarantee that all the relevant bodies will devote great attention to making decisions that respect the sensitivity of the minor and are most favorable for their best integration. Assigning a minor to the same adult or guardian they arrived with in Italy is usually preferable to placing them in a commune because of the previous emotional connection.”

In Italy, cases where the powers of the people who accompanied the children during evacuation are not recognized involve relatives of those children: Sometimes powers of attorney for a grandmother or aunt or other documents confirming their blood relationship with a child or their powers are not recognized, and juvenile courts appoint an official guardian, thus separating children from the people they came with to Italy.

There was a case where authorities did not recognize the right to custody of a grandmother who came to Italy with her grandson and had a power of attorney from the child’s mother. The child was placed in a foster family apart from their grandmother; the child’s mother had to travel to Italy from Ukraine and prove her parental rights in court.

As of late December 2022, statistics for Ukrainian children in Italy show that of 5,042 unaccompanied children, the majority – about 4,200 (83%) – were placed in families and 17% – about 850 children – were placed in institutions. Of children placed in families, 46% were with their own relatives living in Italy (mainly (over half) with their grandmothers), while 54%, or almost 2,270 children, were with families they had no relation to (data from the Ministry of Labor and Social Policies, Minori stranieri no accompagnati (MSNA) in Italia.Ministero del Lavoro и delle Politiche Sociali. 31.12.2022).

Cases of institutional placement and cases where children’s homes retain their structure and functions in emigration have also been recorded in Germany.

In the first days of the war, a social rehabilitation center was evacuated to Germany. This included 35 children aged 5-12 and almost 10 Ukrainian staff members, the director, and the official guardian – a pastor. The children were from troubled families, and their parents had been deprived of their parental rights. In Ukraine, children spent at least two months in the center; they spend six months there on average, but many stay there until they reach the age of majority and even beyond that. There were cases when children left this center and returned from Germany to their parents/guardians in Ukraine, but the majority remained in the institution, since their biological parents or guardians could not or were not interested in bringing the child home during wartime, especially from abroad. Some of the children have relatives who also ended up in Germany and spend some time with the children. There are also so-called “godparents” (Paten) – non-Ukrainian families who talk with the children, take them for holidays, and give them presents.

Family-type children’s homes evacuated to Switzerland are under the patronage of social services and organizations. They help parent-caregivers handle financial problems and receive material and other assistance. However, difficulties can arise in this kind of cooperation because of the language barrier and ignorance of organizational-legal procedures and requirements.

“Communication with the Association [which helps with the upkeep of the children’s home in Switzerland] and its representatives is not good. There’s a problem: We don’t speak German very well yet, so it’s hard for us to convey our position. Sometimes the social workers draw inexplicable conclusions. For example, we were told that we didn’t select the school correctly, but we never even discussed this question.”

Parent-caregiver at a family-type children’s home in Switzerland.

They don’t bring anything on a platter. You have to talk to the social worker, to state what you need.”

Interpreter for Ukrainian refugees, Switzerland.

1.1.2 Removal of children due to problems in refugee families

Sometimes Ukrainian children end up in institutions or foster families in their new countries for other reasons. For example, social services can remove them from Ukraine families if they believe that the children are in a dangerous situation due to domestic violence, harassment, or other serious risks. Scandinavian countries take a rigid stance in such situations – we know of at least five cases where children were removed from Ukrainian families in Sweden

In August 2022, six children ranging from three months to 12 years in age were removed from a large Ukrainian family in Sweden. The reason was complaints from the oldest daughter about sexual harassment by her stepfather (the father of the two youngest children). These suspicions were not confirmed by the investigation, but the children had not been returned to their family at the time of this writing. The older daughter was placed in a special institution because she was found to have psychological problems; the other children were sent to different temporary families and did not speak with each other (except for two children who ended up in one family). The mother was not allowed to see the children for several months and was not told where they were living, even though she was not personally accused of anything and could have acted as the sole guardian for the children. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that the adults and some of the children in the family were Deaf and unable to produce oral speech, using Ukrainian sign language instead. Only one temporary family had Ukrainian-speaking people in it. The other people involved – temporary guardians and staff at the special institution where the oldest daughter was sent – did not know Ukrainian, Russian, or sign language. An attorney retained by a human rights organization, found that the infant was placed in a temporary family even though the conditions there had not been examined in advance. The attorney tried to get in touch with Ukrainian child protective services to get at least a clearer idea of the family and to make sure that the family did not disappear from the social services’ field of vision if they returned to Ukraine, since the children in this family were clearly vulnerable, but communication was very difficult. At the time of this writing, the family was in Sweden; the adults were living together, but separately from the children, whom they were allowed to see. Social services did not return the children to them, because they believed they were not capable of caring for them. One of the arguments in favor of this was that the mother was pregnant again.

A better considered approach to preventing domestic violence and other violations that could result in children being removed from families was noted by respondents in Norway, where Ukrainian parents are informed of children’s rights and accepted parenting standards in the country, which are not always the same as the ones common in Ukrainian families.

“The Ukrainians have a stereotype that children are taken from their families for the slightest pretext. Many are even afraid of going to Norway because of this, probably due to Russian propaganda. It’s the first question: Were your children taken? Of course children are removed, but that’s an extreme measure. I’ve never heard of that happening in our commune, and it is not heard of in general. But what’s good here is that the school held a special lecture for parents. A specialist from Barnevernet (child welfare service) came and provided an orientation. He explained the rights and obligations: you can’t beat children or raise your voice. If a problem is identified, then cooperation with Barnevernet is mandatory – parents can’t refuse it or ignore this assistance. A social psychologist is involved, and an interpreter is present for all consultations with parents. This assistance is very delicate. For example, we have children who cause problems at school. In our case, consultations are initiated by the school. A specialist comes, sits in classes, observes, takes notes.”

Assistant teacher in a secondary school, northern Norway.

1.1.3 Risk of illegal adoption, worker exploitation, human trafficking

Temporary guardians in European countries are warned about the ban on adopting Ukrainian children in wartime (except in cases where the procedure was started prior to the hostilities) and must give their informed consent that the children under their guardianship will return to Ukraine after hostilities end.

In the summer of 2022, there was an attempt to illegally adopt children evacuated from Kirovohrad Oblast from the Perlinka (Pearl) children’s home in Lithuania. The alarm was raised by a volunteer who visited the children’s home before the war and was in touch with children during their evacuation. The accuracy of this account was confirmed by the director of Center Against Human Trafficking and Exploitation in Kaunas and a representative of the Lithuanian Ombudsperson’s Office.

According to a volunteer, as soon as the children left Ukraine for Poland, the children’s home director told the Lithuanian escorts that families from the US were prepared to adopt several of the girls and that he was getting ready to organize their move. This raised the escorts’ suspicion, and they refused to release the children, since their job was to deliver everyone in the whole group to Lithuania. An investigation was launched upon arrival in Lithuania, but the children who were planned to be taken to the US were not isolated from the director and were thus subjected to threats from the director and harassment from other staff members. The details of the investigation were not disclosed, and we do not know anything about the results of the prosecutor’s check. There are doubts that the children were provided with sufficient protection, since most of the children were returned to Ukraine in the summer. At the time of this writing, the girls who experienced the threats and harassment were in the same institution in Lithuania, and their location is known to the director of the children’s home. One of the girls has already turned 18 and feels safe by and large, but the other three girls continue to live under the threat of being returned to the Pearl children’s home in Ukraine. According to the volunteer, they are all in a difficult psychological state and are very afraid of returning to Ukraine and facing retaliation from the directors of the children’s home. Judging by its website, the children’s home is still operation, and nothing is known about the culpability incurred by its directors.

Additional risks faced by children have been documented in Moldova. In these cases, parents who left Ukraine with their children abandon them abroad and return to Ukraine or travel to other countries for work or for purchases. The adolescents live on their own in housing rented by their parents, often without the required support and supervision.

1.2 Discrimination of Roma refugees from Ukraine when crossing the border and finding accommodations in Eastern and Central Europe

The European Commission estimates that there are almost 100,000 Romani refugees from Ukraine. Of these, up to 50,000 are in Poland – these are primarily Roma from Kyiv, Kharkiv, Donetsk, Odesa, and Zhytomyr oblasts (unofficial count of the Romani social organization Towards Dialogue Foundation). It is assumed that the share of children among Romani refugees is higher than among ethnic Ukrainians because Roma traditionally have many children.

Poorer Roma have ended up in countries closer to Ukraine like Poland, Moldova, and the Czech Republic, while Roma who had resources and better standards of living before the war were more likely to go to Central or Western Europe. A survey of Roma from Ukraine who are still in Poland found that a significant majority of them do not plan to go to Western Europe: This is the first time that many of them have been abroad in their lives, and since the reality of the West is unfamiliar to them, it is easier for them to adapt in Poland, which is geographically, linguistically, and culturally closer to them.

“I have never seen such hospitality. When I arrived in Poland, I was shocked that people were trying help however they could. It was hard for me at first, but this is not the first time I have been a refugee. We lived in Donetsk and then moved to Lviv in 2014. When the Russian invasion started, I decided to flee to Poland, since it was the closest country and the language is very similar to ours. I plan to return to Ukraine with my children when the war ends. My children miss their home terribly, and our roots are there.”

Female Roma refugee, 36, living in a refugee center in Warsaw at the time of this interview.

1.2.1 Problems with documents

A unique feature of migration among Roma is that they move in large family groups. Here is a typical documented case: a family group from Mariupol made up of 11 adults and 25 children from infants to older adolescents was forced to emigrate through Russia and cross the border in Narva (Estonia) to make its way to Germany (interview with ADC Memorial, June 2022). Considering the endemic problem of identity documents for children and adults, Roma face the risk of being detained abroad.

In a report (March 2022), the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) says that Roma children escorted not by their parents but by other adult family members were often refused entry into Moldova and EU countries. In Hungary, about 10%-20% of Roma trying to cross the border were undocumented. Roma sometimes tried to use baptism certificates as personal identification, but such documents were not always accepted. Our monitoring studies identified problematic situations in Lithuania, Poland, and Moldova that arose on the border because of a lack of documents.

There have been frequent cases among Roma where early, unregistered marriages caused problems crossing the border. In these cases, an adolescent under the age of 16 was viewed as an unaccompanied child without legal representatives (Art. 313 of the Ukrainian Civil Code bans children under the age of 16 from leaving the country on their own). Such cases have been documented at the border with Moldova, for example.

Roma who are stateless or are citizens of other countries but who permanently reside in Ukraine and have suffered from the war face bureaucratic barriers when attempting to register and receive assistance. There have been cases when members of one family, who were citizens of Moldova, attempted to receive protection in Lithuania as refugees from Ukraine and were not able to do this because they could not prove that they actually lived in Ukraine.

There are probably many cases like this, since approximately 10%-20% of Roma living in Ukraine are stateless or are at risk of statelessness (report: Stateless people and people at risk of statelessness forced to flee Ukraine. European Network on Statelessness. 10 March 2022).

“My husband and I crossed the border through Moldova and then went to Poland. We lived in Ukraine for 20 years before the war. My husband is 70. He only has a birth certificate issued in the Soviet Union. My husband got sick, and we didn’t get him a new passport after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. He is now a stateless person.”

Roma woman, 59, refugee from Kherson Oblast living in Poland.

A group of Zakarpattia Roma from Ukraine with Hungarian citizenship were vulnerable in terms of documents. According to a study by the Romaversitas foundation, they did not receive assistance in Hungary or other EU countries, even though they were theoretically entitled to the same benefits as other Ukrainian citizens. In May 2022, the Czech Republic tightened rules for receiving refugees from Ukraine that did not offer temporary protection to people who were citizens of EU countries. The Czech Ministry of Internal Affairs announced its intention to send Hungarian citizens to Hungary, in particular Roma, who were living at the central railway station in Prague. In June 2022, the Czech authorities closed the assistance center at the railway station because it was overburdened and, as a compromise, set up a tent city for Roma in a district of Prague, where Roma with Hungarian citizenship were placed. The idea that the majority of Roma in the Czech Republic had Hungarian citizenship was used as a pretext for refusing assistance. An independent study by PAQ Research (August 2022) refuted this: Only 150 Roma out of over 5,000 had Hungarian citizenship.

1.2.2 Problems with xenophobia and discrimination

Unfortunately, even Roma families from Ukraine who reached safe neighboring states faced significant problems with integration, xenophobia, and restrictions on social opportunities. Roma suffer from stereotypes and poor attitudes on the part of local residents, other Ukrainian refugees, volunteers, and officials.

“I am so upset that if something happens, everyone will think that the Roma are to blame. If something is stolen, they think it must be the Roma. I’m tired of always proving that I have nothing to do with it.”

Roma woman, 40, living in Warsaw.

“I was at the train station where volunteers where giving out free kits to Ukrainian refugees. I wanted to take one for myself and my daughter. Then I heard them speaking amongst themselves: Roma aren’t Ukrainians, so why should we give these kits to them. I was very offended and wanted to object, but I just wasn’t up to it. So I started to not react.”

Roma woman, 45, living in Poland.

By April 2022, the independent European media network Euractiv was reporting that many Roma fleeing to Hungary because of the war in Ukraine were gradually returning home because of discrimination and refusals of humanitarian aid. In November 2022, the independent study “Solidarity with Ukrainian Refugees in Hungary” was published. This report revealed the lack of desire on the part of humanitarian organizations to place Roma in refugee centers, the lack of opportunities to rent private housing, the major lack of information, and, overall, the absence of assistance on the part of the Hungarian authorities and humanitarian organizations.

Many Roma were forced to return to Ukraine from the Czech Republic or move on to Western Europe because of a lack of humanitarian aid and because the local authorities did not take any actions. Volunteers from the “Czechs Help” initiative reported (March 2022) that some Czech dormitories evicted Roma who fled Ukraine with no grounds. In December 2022, Czech human rights defenders released a statement about the continuing difficult situation of this particularly vulnerable groups of refugees. Many did not receive medical care because staff at refugee centers undermined this, while children did not attend local schools. An investigation conducted by the office of the Czech humans rights ombudsperson at several refugee assistance centers showed that Roma were only allowed into the registration center if they were escorted by NGO staff or police officers, while other Ukrainian citizens were able to enter on their own. The Roma were expected to have housing as a prerequisite for temporary protection applications, even though this was not a requirement for other refugees.

An independent study by PAQ Research (August 2022) showed that one-third of Roma refugees from Ukraine faced intolerance in the Czech Republic, while one in six encountered discrimination of the part of the government. In June 2022, the mayor of Bílina (Czech Republic) said that Roma from Ukraine would not be allowed to live in her town. Citing the complex socioeconomic situation in the region and a similar statement by the Ústecký Region governor, she called Ukrainian Roma “unadaptable” – a term that the Nazis used about the Roma population during World War II. In late June, the Czech Refugee Affairs Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs gave into the racist attacks from the mayor’s office and rejected plans to house Roma women and children in the city. It’s worth noting that anti-Roma populism also met with organized resistance: In May 2022, ministers and parliamentary deputies in the Czech Republic left a meeting in the Chamber of Deputies after a right-wing politician made racist comments about Roma refugees from Ukraine

Activists who help Roma refugees in Poland reported that Roma are often not allowed into refugee reception centers or even railway stations because they are blamed with being aggressive and stealing. Cases of discrimination have been recorded on the part of volunteers when Roma are crossing the border (Roma were identified by their appearance and sent to the end of the line). Dormitory managers have turned away and thrown out Roma, volunteers have refused to give them the clothes they needed, and Ukrainian women did not want to share a room with Roma women, saying that they are “dirty,” and so forth.

Discrimination has also been allowed by officials: In the summer of 2022, the conductor of a humanitarian train from Przemyśl to Hannover prohibited Roma from sitting in the same car as other refugees, and the mayor of Przemyśl prohibited the assistance center from accepting Roma.

“The mayor kept watch at the station all night, making sure that we didn’t take any Roma to the assistance center at Tesco, even though we had over 400 free beds. Even just to sleep for a couple of hours. At the same time, right in front of my eyes, almost 50 Romani children and their parents were forced to sleep on the platform, right on the pavement surrounding the station. He even sent away the taxis we wanted to use to take them to the center and told our volunteers they couldn’t help them. After that, the mayor came to the center. He was looking for me, threatening to arrest and deport me, even though the only thing I’d done was put five Roma in a car so a volunteer could drive them to the center to spend the night. Some of the family was already with us, one child had a heart problem.”

Member of a group of volunteers helping refugees, June 2022. Report ADC Memorial, Roma From Ukraine: A Year of War and Flight, April 2023.

Finally, the Polish ombudsperson took control of the situation with discrimination against Roma in Przemyśl in late November.

Cases of discrimination on the part of several charitable initiatives have been recorded in Romania. For example, a large group of Romani refugees complained that they were refused humanitarian aid in Budapest. The incident was caught be a camera and sparked criticism of the group giving out the food.

1.2.3 Housing segregation of Roma refugees

Roma in a number of countries have been segregated from other Ukrainian refugees. In May 2022, the Moldovan media found that Roma refugees, Azerbaijanis and members of other minorities in Chisinau are usually housed separately. A CNN report that came out in August 2022 described an abandoned university building in Chisinau that was turned into a shelter for refugees as an example of the terrible living conditions of Ukrainian Roma in Moldova. The building where over 100 refugees – almost all Roma – lived had only one working tap with drinking water; a portable shower room provided by UNICEF was set up on the street. The Moldovan government’s Crisis Management Center denied intentionally segregating Rome refugees from other Ukrainians in the shelter, saying that they were placed there so as not to separate “large families of ethnic Roma that cannot be placed in various centers.”

The practice of segregating Roma in separate, poorly equipped shelters has also become widespread in Poland. Humanitarian organizations explained this as a desire to avoid tensions and conflicts between Roma and other Ukrainian refugees.

According to reports from Romea.cz, Ukrainian Roma at the Czech refugee reception center Černá louka were housed in a special area separated by tape and overturned tables. They were not allowed to leave the place allocated for them, and they could only go to the bathroom if they were escorted by staff at the center. According to Czech NGO staff and activists, Roma families were mainly placed in tent camps, while tens of thousands of other Ukrainian refugees were provided with shelter in private homes and comfortable dormitories. The camps turned out to be the only place where Roma could find shelter, so their closure by the authorities (for example, a camp in Brno where Ukrainian Roma who had previously stayed in the railway station lived was closed because there was supposedly no need for it) became a critical problem.

Segregated housing for Roma in temporary camps in Hungary made it impossible for Roma children to enroll in school (along with the fact that many schools did not want to accept these children).

Even though Western European countries have not typically placed Ukrainian citizens in refugee camps, this practice does exist in Germany, and cases have been documented where a large percentage – if not all – of the camp residents were Roma:

“After Latvia, we went to Poland, and then on to Germany. We registered at a refugee camp in Berlin. We were there for two days and were then sent to a different camp in Giessen. It was absolutely terrible there. It was very dirty and messy. There was trash everywhere. We simply couldn’t live there and decided to leave, even though the administration said we couldn’t. They said that we were already registered with them, that we had been fingerprinted and could only be there. Still, we decided to risk it and, following our relatives’ advice, we went to Hamburg. From there, we ended up at the camp in Boostedt. This was a very nice camp, where half of the residents were Ukrainian Roma, mainly from Kherson and Mykolaiv oblasts. This was a great joy for us, because we knew almost all of them personally; we constantly visited each other, talked, went into town together, and so on. We hoped that we would be left there permanently and not moved anywhere else, because we were all happy with it. But three weeks later, we were told that a new group of refugees was coming and we would be moved to another camp. After we left, that camp only had Romani people. Now I think that maybe the camp administration didn’t understand that we were Roma, so they decided to send us to a different camp. In any case, the day after we left, a large group of our relatives arrived there, and there were no problems finding space for them.”

Interview with a Roma refugee from Kherson, Germany. Report ADC Memorial, Roma From Ukraine: A Year of War and Flight, April 2023.

Roma had a harder time finding housing outside of centers not just because of xenophobia and bias, but also because Romani people usually left Ukraine in large families and it was harder to find housing options for them than it was for a family of two or three people. Examples of cooperation between social services and volunteers on this matter and assistance finding housing or at least neighboring rooms were found in a number of countries.

In the spring of 2022, a Roma family of 13 staying in a temporary center in Lithuania was in need of public housing. It was quite difficult to find any options for such a large family in a short timeframe, but the family was ultimately offered housing where they could all live together.

The fact that many Romani families in the first wave of emigration were not received in Europe on equal footing with other Ukrainian refugees, had no choice but to return to Ukraine, and then had to seek refuge abroad again following the escalation of the war in the fall had a very unfavorable effect on children and their physical and mental health, education, and integration.

1.3 Problems of evacuation through Russia

In wartime, residents of temporarily occupied territories and, often, frontline regions of Ukraine, do not have any way to reach the EU or territories controlled by Ukraine than by passing through Russian territory. The trauma of this kind of evacuation includes a long trip requiring money, filtration at checkpoints, and the risk of being detained and subjected to interrogation and torture.

A dangerous route is moving from occupied territories through unofficial border crossing points, which respondents called “backdoor paths.” This kind of crossing is handled, for a large fee, by private operators that drive people to the border. Then these people must walk through “no man’s” land and then switch back to vehicles once they reach the Ukrainian side. For example, people from occupied Luhansk Oblast can reach Ukraine’s Sumy Oblast through Russia’s Belgorod Oblast. Refugees undergo checks, interrogations, and filtration on both sides of the border.

Unaccompanied children also navigate this path. Below is the story of a 16-year-old adolescent from a village in the Donbass region that is in Ukrainian-controlled territory but is close to the border of the so-called “people’s republic.” By 22 February 2022, the village was occupied by soldiers of their “people’s republic.” The boy left Kyiv for Europe, where his older sister was living, and it took him an entire week to reach Kyiv from his village: First he went through Belgorod Oblast, then through filtration points into Sumy Oblast, Ukraine, and then on to Kyiv from Sumy.

“In 2022, the war started where we were on 15 February. We woke up to a terrifying roar on 24 February. They were firing Grad, Torpedo and Smerch [missiles], thousands of missiles were flying at us. We figured that they were already shooting at Kharkiv. We were at the frontline, so we had to crawl down into the basement… When we crawled out of the root cellar, we heard screaming over a loudspeaker: ‘Ukrainians, surrender! The Zelensky regime has fallen. Save your own lives.’ But there was no one to surrender to: The Ukrainian Armed Forces left 24-25 February. They even abandoned two tanks. In the square, they hung up flags [of the ‘people’s republic’], the flag of the Don Cossacks – a deer pierced with an arrow, the Russian flag… There was no longer an opportunity to reach us from unoccupied Ukraine or to reach unoccupied Ukraine from where we were. An acquaintance tried to get home. They were shelled, four shuttle buses. Everyone died.

At our passport office, they started issuing ‘people’s republic’ passports. Anyone who didn’t receive a passport had to get a pass there. Parents started to be afraid of the military recruitment office and army mobilization [for the ‘people’s republic’]. All the older kids at school were added to the military register.

I decided to leave at the end of 2022. A courier took me along a ‘backdoor path.’ We took a bus to Belgorod, in Russia. I told everyone I was ‘going to my uncle’s to celebrate New Year’s’ [there is no uncle in Belgorod]. It was expensive, but my payment was helping an 88-year-old woman in a wheelchair [the boy’s way was paid by this elderly woman’s relatives]. We drove into Russia, but it turned out we had to pass through a checkpoint during our approach to Belgorod (an emergency had apparently been declared in the city). They checked documents, they checked everyone in databases. I was taken to the district department to be interrogated. I asked the old woman for a sedative. I was so nervous I couldn’t speak. I was shaking. Russian police officers interrogated me for a long time at the district department of the village NN. It was terrifying. A cop with an automatic weapon was standing over me. During the questioning, I gave the address where is was supposedly going to visit my ‘uncle.’ There was a question: ‘how do you feel about the war.’ They took my fingerprints and forced me to give a spit sample for my DNA. I was only released toward morning. The entire bus waited for me until morning. The old woman’s blood pressure was close to 200.

We drove through Belgorod to a checkpoint in NN. That was already the border, Sumy Oblast, Ukraine. I was also interrogated there, this time by Ukrainian border guards. Then at the filtration point they checked my phone. Then soldiers questioned – ‘was I cooperating with the occupiers, had I seen equipment.’ It wasn’t as scary. I told the truth, that I was going to my sister. The hardest was ‘no man’s land’: I had to carry the old woman, her wheelchair, and all her stuff on my back for three kilometers – the tires on the wheels were flat (they may have been pierced by Russian border guards), the road was deep in mud, and we had to walk on foot. Later I was covered in bruises from this.

Then we took a bus from Sumy to Kyiv, where I was met by acquaintances. I was wearing a smart watch. It showed that I had slept two hours that week.”

Interview with ADC Memorial, April 2023, in a European country.)

Legal border checkpoints for entry into the EU are far from the theater of war: Refugees must cross all of Russia from the south to the northwest to reach the border with Estonia or Finland, or make their way into Latvia through Russia and Belarus. Below if the testimony of a Romani woman from Mariupol whose family had to escape through Crimea and Rostov, travel to St. Petersburg, and cross the border in Ivangorod/Narva to reach Germany.

We left on our own, in our own cars, which were still intact. There were about 40 of us. There were six cars. They were all crammed with people. Other Roma left Mariupol with us. There was a total of about 150 people. We headed in the direction of Kerch. From there, we decided to make our way to Rostov, to our relatives. It was already impossible to head in the direction of Ukraine – there were Russian soldiers everywhere, and they only let people through in the direction of Russia.

We went through 27 Russian checkpoints from Melitopol to Crimea, to Dzhankoi. We were stopped at each one, and our cars and our persons were thoroughly searched. They look at the men particularly carefully: They forced them to undress and looked for marks from gun butts. We didn’t get any sense of particular dislike from the soldiers. They treated us normally, but it was still terrifying every time the soldiers approached the cars and forced us to get out and explain who we were, where we were going, and so on.

We arrived in Kerch at 1 a.m. We stopped there to rest. Some people noticed us. They saw that our cars had Ukrainian plates and offered to help us. It turned out they were some kind of officials. We were put up in a hotel, where we spent the night and were fed. In the morning we went on to Rostov. The administration even offered an escort to Rostov, but we refused because we would have had to wait a long time and we were scared that there would also be shooting in Kerch. That’s how we ended up in Rostov. Our relatives took us in, and we lived there for almost two months. We were able to earn a bit of money there. We mainly worked in private gardens – digging and collecting trash for 100 rubles an hour. Then those who wanted to went on further. Some stayed in Rostov. Thirty-six of us decided to go to St. Petersburg and then on to the Baltics and then Germany. People said it was quieter there and you can earn a living. I have a son there.

Romani from Mariupol, interview in Estonia, June 2022. Report ADC Memorial, Roma From Ukraine: A Year of War and Flight, April 2023.

International volunteer groups, whose Russian members often operate in deep secrecy because of the risk of persecution by the Russian authorities, help refugees leave temporary accommodation centers in Russia, travel the long route to the border, cross the border, find the best route on the European side, and find money to cover all this and sympathetic people to house refugees, feed them, and provide them with clothing and other necessary items.

“A question came up in our volunteer chat: Who can take a young woman to the Estonian border in Ivangorod? She has a disability and is very young, but she’s of age. The only document she has is a Ukrainian birth certificate. I was available, and I had a car, so we set off. Problems arose at the Russian border: They didn’t want to let her through because she didn’t have a passport. I was present for this because I had to be sure that she made it across the Russian border and that other volunteers met her on the other side of the bridge in Narva to accompany her to Europe. I was taken to a separate room, and an officer questioned me for a long time: Who are you? What is your relationship to this young woman? How did you find out about her? Who told you to bring her here? And I said: you know, we have a volunteer chat. I don’t know anyone’s name; we’ve never met. I’m available and they write: we have this prospect, at this address, 3rd entrance. Drive up at 10, a young woman will come out. Drive her to the border, that’s it. Anyway, we spoke for a long time. In the end, he said: okay, we’ll let her through when the shift supervisor leaves. And that’s what happened.”

Volunteer, St. Petersburg. Interview with ADC Memorial.

“The first stream of refugees from Mariupol started arriving during the first days of March 2022. There were many Romani people among them. They all came through Taganrog. After that, some went to various refugee centers, while others made their way to the border on their own and went to Europe. The people who were in refugee centers and were not able to travel independently tried to contact volunteers and then travel to the border with their help. For example, several Romani families, a total of 58 people, at a refugee center outside of Shatura, Moscow Oblast, got in touch with us in March and asked for help arranging travel to the EU. It was very difficult to find transportation for such a large number of people, so we had to transport one group first and then the other. Since they were afraid to travel to Europe separately, we had to find a place for the first group to stay in St. Petersburg while waiting for the others. We had several people with large apartments in St. Petersburg, so that’s where we normally housed refugees. Aside from this large group, small Romani families also came. We also often housed them with volunteers, since they needed time to recover after this major shock and the long journey.”

Volunteer, St. Petersburg. Reports ADC Memorial, Roma From Ukraine: A Year of War and Flight, April 2023.

For Roma, the problem with documents is related to the fact that they have close blood relations in both Russia and Ukraine, have always moved between the two countries, and have documents from before the war in both countries, including birth certificates for their children. All of this becomes a barrier to crossing the border.

“For example, we had a family of 15 from Mariupol. The reverse side of one of the children’s Russian birth certificate said that he was a Russian citizen. So he couldn’t leave Russia for Europe because he didn’t have a visa. After this case, we started carefully checking all their documents and asking for additional information, photos of the reverse sides of their birth certificates, and so on. We have a pretty complex case right now, and we don’t know what to do. There is a Romani family from Mariupol – three children and their mother. The father has already left for Germany, and they’re following him. One child’s documents were all in order. The second had a Russian birth certificate, but it was written on there that both parents were Ukrainian citizens, so there shouldn’t be any problems with that. But somehow the third child’s birth certificate has a stamp saying he’s a Russian citizen. This was most likely some kind of mistake, but this mistake could cost us a huge amount of time, nerves, and money, because in these cases there is no procedure for renouncing citizenship, so we will probably have to prove in court that the document was stamped by mistake. There are Roma whose families we sent to the EU but who are themselves Russian citizens. These people don’t have any legal way to leave Russia right now. They need to wait until their relatives return or become naturalized in the EU, and then they can submit documents for family reunification to the embassy and wait for a humanitarian visa.”

Volunteer, St. Petersburg. Report ADC Memorial, Roma From Ukraine: A Year of War and Flight, April 2023.

Roma trying to leave Russia for Estonia were not let through by border guards from either country:

“We have had several cases at the border crossing in Narva when they didn’t want to let Romani people through because of their registration. A family was traveling from Mariupol, but one of them had a residence permit for Mykolaiv, which is under Ukrainian control. This raised a lot of questions for the border guards. They didn’t believe that this person was telling the truth and was really a refugee. They could have said: ‘Okay, you and you, go ahead, but this one has to stay because he’s not registered in Mariupol.’ However, it’s clear that a person from a large family could be registered in one city and live in another, or that he was visiting when the war started. As far as I know, none of these cases have ended badly. Everyone was let through in the end. But these situations took up a lot of time and nerves for both the Roma and for us.

…In terms of Russian border guards, there have also been cases where people stood in line for seven or nine hours, or even for entire days. The guards asked them many questions when they were checking their documents and did everything very slowly. They would fixate on passport photographs or some other document. But everything worked out fine with the Roma that we helped leave.”

Volunteer, St. Petersburg. Report ADC Memorial, Roma From Ukraine: A Year of War and Flight, April 2023.

Human rights defenders have noted violations of human rights, including children’s rights, on the part of Estonian and Latvian border guards, who deny temporary protection to refugees arriving via Russia or Belarus and do not allow them into the EU, using the phrase “a threat to EU security.” Their decision to refuse entry is based on the fact that these refugees spent too much time in Russia and cannot therefore be trusted. People denied entry include people with a residence permit for the so-called “DPR” and “LPR” or people who hold passports from these unrecognized entities; multinational families where one member has a Ukrainian residence permit but not Ukrainian citizenship; and people with a criminal record, even if it is expunged or involves minor offenses. In these cases, the refugees must either return to Russia and try to appeal the denial, leave for the EU through another country (for example, Finland), or file a petition for international protection following standard procedures at the border crossing, which means that it will take much longer to cross the border and that it will be difficult to receive assistance.

“For example, there’s a family of four adults and a one-year-old baby. They don’t let the baby through because he was born in occupied territory and is recorded as Russian. Naturally, the family is not going to leave him and cross the border. However, the denial is written for only one family member. In the same way, they don’t let people through who have a Russian passport.”

Lawyer, Center for Human Rights (Estonia). Material of Radio Liberty, 30.03.2023: “ ‘Threat to EU Security.’ Why Ukrainians aren’t being let into the Baltics.”).

2. Life of ukrainian refugees in emigration: main problems

2.1 Access to education

European countries officially guarantee Ukrainian children access to education without discrimination as part of national school systems, as well as additional measures of support proclaimed in connection with the military crisis (summer schools and language camps, additional financing for language courses and bridging classes, priority registration preschool, stipends for students, and so forth). The selection of an individual education trajectory (bridging classes, learning with children of the same age right off the bat, continuation of studies in Ukrainian schools online or in combination with a local school at the place of emigration) depends, of course, on what a specific country offers or allows for refugees, the child’s age, and the views and capabilities of the parents. School is free, and many countries give children all the required textbooks and school supplies.

“Everything (for school) is free. They came, and everything was already in their desks – textbooks, workbooks, even book covers.”

Mother of a 7-year-old child with disabilities and special educational needs, Switzerland.

“They give out textbooks, notebooks, and pens for free. If I run out of pens or notebooks, I can go tell the teacher, and he’ll give me new ones. We do buy some things ourselves.”

Adolescent, 16, Switzerland.

Educational problems like the language barrier, incompatible learning programs and timeframes for passing exams, a lack of teachers trained to work with second language learners, and a lack of resources cannot be avoided in a situation of mass migration and are handled differently depending on the country. But it is clear that the need to learn in a non-native language or take two programs at the same time (Ukrainian and foreign language programs) creates an additional burden for children, often lowers the effectiveness of instruction, and sometimes means that children drop out of school.

It’s hard to say how many children are receiving a school education in a particular country because of the rapidly-changing situation and the shortcomings of methods for calculating this. However, Ukrainian children in even the most prosperous countries do not always receive a school education. As of July 2022, Spain and Italy had fairly high indicators – of almost 38,000 registered Ukrainian refugees of school age, 75% attended school in Spain, and 71% attended school in Italy. This figure stood at 66% in the Netherlands and 53% in Belgium. Germany (39%), Poland (37%) and the Czech Republic (38%) had similar numbers (report of Eurydice: European Commission / EACEA / Eurydice, 2022. Supporting refugee learners from Ukraine in schools in Europe. Eurydice report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, July 2022).

More recent data from a Save the Children study in Poland (November 2022) shows that less than 41% of children from Ukraine attended Polish schools. The situation was similar in Lithuania: According to the Lithuanian Education Ministry, as of October 2022, 11,936 children from Ukraine were enrolled at Lithuanian educational institutions (2,893 in preschools, and 9,070 in schools). However, data from the Department of Statistics shows that close to 20,000 children of school age (6-17) from Ukraine were registered in the country. Thus, about 47% of refugee children of school age attended school in Lithuania. This major difference in indicators is not just because children returned to Ukraine or moved to a different country without being removed from school education lists, but also because an ostensibly significant number of children withdrew from school, including because there was not enough space, while schooling is regarded as an obligation, and the failure to attend school could serve as a reason for denying temporary protection status.

“We live in Prague 7. We went to all the district schools and directly to the magistrate, but they never found a place for my son in school. He hasn’t been attending school for four months now.”

Female refugee, Czech Republic.

As far as we observed, the children most vulnerable to dropping out of school were the children whose families moved from country to country or returned to Ukraine periodically and then went abroad again. This was particularly true for Romani families, who tried to set up their lives in Eastern European countries in the first months of the war, then returned to Ukraine after facing discrimination and difficulties, and then emigrated once again in the fall of 2022, when the Russian Army launched its mass shelling of civilian infrastructure in Ukraine. In addition, many families who exhausted the financial and social assistance offered to them and were able to find work tried to move to European countries with deeper pockets.

In August 2022, a Romani family from Boryspil, Kyiv Oblast (mother, two sons aged 8 and 17, one daughter aged 7) spent about a month in an arrival center for refugees in Brussels, even though refugees from this center were assigned to families or other residential options fairly quickly. They went to Poland during the first days of the war and stayed there until 1 July while they were provided with free housing and food. All three children went to school. When the benefits ran out, they moved to Belgium, because they were told in Poland that things were good in Belgium, that the benefits were very good and it would be possible not to work. This family didn’t have any ties with Belgium or any friends or family there. They didn’t have any money to live on or provide for an independent life. Housing could not be found for this family for almost a month; the mother said it seemed like no one wanted to take them into their families. Obviously, the children were at high risk of dropping out of the educational system.

Interview, Brussels, August 2022.

2.1.1 Bridging classes vs. general classes, in-person learning vs. distance learning in Ukrainian schools

Many children and parents/guardians in Europe were surprised to learn that school was mandatory and a condition for their legal stay in the country – they had counted on only continuing remote learning at their Ukrainian schools.

“We arrived from Kyiv in late March [2022]. We were invited to a school in mid-April, but now I understand that it wasn’t even a school, but a general course for Ukrainian children. The Germans were afraid to leave us at home. As my mother explained to me, all children must go to school without exception or their parents could have problems. I didn’t want to go to school, since I attended a Ukrainian school online, and this was enough for me. But it wasn’t my decision, it was my parents’. I went to a German school until August. I didn’t like how the teachers and students ignored us. They didn’t notice us.”

Girl, 15, refugee from Kyiv in Bavaria (Germany).

Young people over the age of 18 who were already attending Ukrainian universities and institutes were also required to attend school, which caused confusion (report from Italy).

A Euridice report says that most European countries had Ukrainian children attending regular classes while it provided them with intensive language support. In many countries, the prevailing system is one of bridging classes along with a certain amount of time in general classes – there are high-level directives for this kind of approach in nine educational systems: Austria, German-speaking communities in Belgium, Greece, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, North Macedonia, and Finland. Both approaches co-exist in a number of countries (like Spain and Germany) and are used depending on the children’s age and other features, their number, and the school’s capabilities.

Ukrainian children and parents have different feelings about bridging classes depending on their personal experience, the flexibility of the host school system, and the efforts of specific schools and teachers to integrate Ukrainian children. Children often express disillusionment and skepticism:

“I want to return home to Ukraine. I’m foreign here. We’re not given the chance to be like normal German children. We go to one class in school where everyone is Ukrainian, where we’re all different ages and have different levels of knowledge. I don’t think this helps us at all; it actually harms us. My mother is always nervous and worried about what will happen next.”

Boy, 11, refugee from Mykolaiv Oblast in Germany.

“I went to a German school, so I can’t go to my Ukrainian school. My mom and I evacuated from Kyiv Oblast in mid-March [2022].We had a long journey and ended up in Germany. When I first got to the German school, I felt nervous because I’m a foreigner and we weren’t really welcome here. After a month, they started letting us into age-appropriate German classes, so that we could gradually integrate and meet kids in the classes. But I saw how the German children looked at me. I didn’t understand the language, but I knew that they were laughing at me. I got support from Ukrainian friends who are the same age and have the same story as me. We all fled the war and were forced to stay here for a time. If it hadn’t been for them, I would have wanted to run away from that school that very day…”

Boy, 15, refugee from Kyiv Oblast in Germany

“My daughter, 11, attended school but was very unhappy that they created a Ukrainian class for 8 to 12 year olds. They joined a regular class with Belgian children for their Dutch class, but the teacher did not work separately with the Ukrainian children. The school held a five-day language camp. My daughter didn’t like it there. She went twice and then categorically refused to go again. She will go to a different school when the next academic year starts.”

Mother of 11- and 18-year-old girls, refugee from Odesa in Belgium.

Our adolescent respondents said they preferred regular, age-appropriate classes, but their attempts to accelerate the transition to general classes were not successful:

“All the Ukrainian children were in one class, and I really wanted to be in a German class with my peers. I decided to go to the principal and ask her to let us attend German classes more often, more than three times a week would be better. She listened to me, but then just laughed, didn’t say anything, and left. I understood that this was a refusal and that she didn’t care about my request. They have no need for us, and we’re just a burden for them… It took me a long time to recover from this non-dialogue with the principal, from this monologue. I didn’t even tell my mom so as not to upset her. I’m waiting for the war to end so I can go back to my native city.”

Girl, 14, refugee from Kharkiv Oblast in Germany.

“I had one incident in a German school. We were sent to German classes on certain days so that we could adapt, and then we were sent back to Ukrainian classes. But my friend and I decided to go to English with the German class, since I liked English better in those classes. We had only been sitting in the English class for a couple of minutes when the principal read out our names over the loudspeaker and said that we have to return to our Ukrainian classes right away… All the kids were laughing and pointing at us, because they understood it was us…”

Girl, 13, refugee from Odesa in Germany.

Our respondents living in Switzerland said German was not taught effectively in bridging classes and that the local school program was not as difficult as the school program in Ukraine.

“There’s no individualized approach to education. All the children are in one class from 6th to 10th grade. There’s no program. It feels like it’s all made up as we go along. The textbooks are only in German, and they stay in school since there is no homework. In the end, the children can’t even learn German because they don’t speak with local people. The children have no motivation to speak German. The ones who go to on-the-job training know the language a little better. Basically, the children have missed a year and a half of academics.”

Parent-caregiver at a family-type children’s home in Switzerland.

“I attend an integrated class. Swiss teachers teach German and math. They speak in German, I don’t understand everything. Ukrainian is taught by a teacher from Ukraine. We take tests and write dictations in Ukrainian. Our textbooks are only in German. They don’t give homework.”

Young man, 18, ward at a family-type children’s home in Switzerland.