A heated discussion about family separation has been raging since 2018. The US practice of separating children from adult family members and holding them in detention camps caused broad public indignation after it emerged that adult migrants at the US-Mexico border were being sent to federal prisons while their children were being labelled “unaccompanied” and sent to detention centers without any stipulation of how they could later be reunited with their parents. It is difficult to say exactly how many children have been taken from their parents at the border, but estimates reach into the thousands.

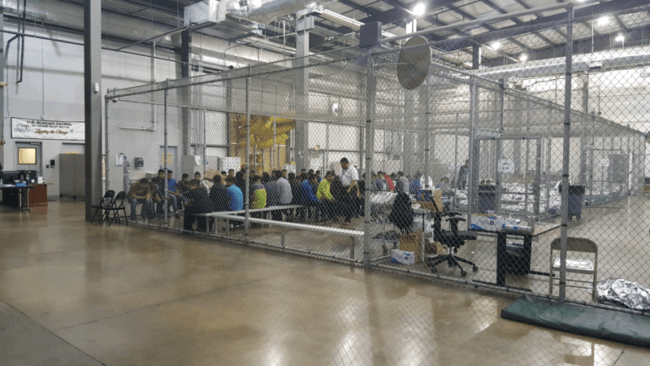

Even though the United States ended family separation under pressure from international organizations, many children have remained in detention centers, where intolerable detention conditions have been documented. In some cases, children have been placed in large cages and have not been provided with nutritious food, bed linens, clean clothes, or personal hygiene products.

Unfortunately, family separation is practiced not just in the United States: Police and migration officers in many CIS countries conduct repressive raids that end in children being separated from their parents. The parents are then sent to a special institution while their children are sent to the hospital and then on to a closed children’s facility, where they are often deprived of an education, for an extended period.

Opinion of pediatricians

Human rights defenders are not the only ones outraged by family separation—pediatric health specialists have also been sounding the alarm. In fact, the connection between family separation and growing problems with a child’s physical and mental health has been long known and is well documented.

Researchers at The Bucharest Early Intervention Project demonstrated the negative impact that institutionalization at an early age has on children’s cognitive development and behavior. This study was conducted in Romania, where thousands of children were kept in overcrowded children’s homes under Ceaușescu.

The Bucharest Early Intervention Project showed that being kept in an institution without family members is harmful to a small child’s development and can delay the development of cognitive skills, increase the risk of psychological disorders, and stunt physical growth. These studies are also relevant for understanding the physical, psychological, and mental states of migrant children in closed institutions. Charles Nelson, who worked on the Bucharest project, is a neuroscientist and psychologist at Harvard Medical School. Nelson has stated that children who are separated from their parents and placed in a closed institution lose their sense of being protected and experience trauma that could result in changes to brain structure and cause long-lasting emotional, psychological, and physical damage. The absence of a parent or guardian also often signifies the loss of a nurturer who can stimulate a child’s development.

In describing the situation with family separation, Nim Tottenham, a psychologist and director of the Developmental Affective Neuroscience Laboratory at Columbia University, used the term toxic stress, i.e. strong, repetitive, and/or prolonged adversity without adequate adult support, which can impact a child’s entire future life. According to Tottenham, when children are in a state of toxic stress, the brain and body are fixated on ensuring immediate survival. But children are especially vulnerable because they are experiencing major brain development, which means survival takes priority over things like academic development and physical growth. The long-term effects of toxic stress have been confirmed in a study published in the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Even though toxic stress is not as visible as, say, a broken arm or leg, it can leave a lasting mark on a child’s brain and destroy the foundation for future learning, behavior, and health.

Alan Shapiro, a clinical professor in pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and co-founder of Terra Firma, a group that provides migrant children with access to medical care, has also spoken about the chronic problems children in institutions have with their health, education, and growth and development. Shapiro identifies the short-term and long-term effects of stress on children in closed migration camps. In the short-term, children develop regressive behavior, which may include withdrawal, bed-wetting, and mutism. Institutionalized children have elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol (which manages response to danger), and this level does not drop, because children in these camps feel that they are in constant danger. This results in chronic medical problems. Pia Rebello Britto, who is the chief of the Early Childhood Development Division at UNICEF has stated that the negative effect of elevated cortisol levels impedes the formation of new connections in the nervous system and destroys old connections. This means that children often lose the stimulus they need to develop and learn, which makes it difficult for them to return to regular development.

Child psychologist Gilbert Kliman shares Rebello Britto’s point of view. When the United States started separating migrant children from their parents and placing them in institutions, Dr. Kliman surveyed dozens of migrant children in shelters. He concluded that children can return to their normal lives after reunification with their parents, but noted the short-term consequences of separation in the form of night terrors, anxiety, and trouble concentrating, as well as long-term consequences like increased risk for psychological and physical problems such as depression and cancer in adulthood.

A child’s age is quite significant when considering matters related to trauma, stress, and problems with early brain development. According to Jack Shonkoff, director of the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, an infant who experiences trauma will remember the fear and anxiety of their early years even if they later end up in a stable environment. Nelson warned that for young children, even a short period of waiting can seem eternal: time stands still for children while they are waiting, which leads to a sense of tremendous despair and hopelessness. In addition, as an International Detention Coalition report notes, young children cannot understand why they have been detained and fear that this detention will last forever. Shonkoff also believes that for children, the trauma of separation from their family is akin to kidnapping.

Nelson and Shonkoff admit that the length of time children spend in closed facilities is also important: The longer a child is kept in a situation of stress without any stimuli for development, the worse off the child will be. At the same time, though, studies have shown that even a short period of detention can cause long-term harm to a child. Pediatrician Julie Linton has studied the detention of migrant children and noted that the enormous stress of family separation affects children’s immune systems. Children become indifferent and may experience fits of anger, speech problems, and difficulties completing tasks. Lipton has emphasized that even a short time in detention is dangerous for the health and development of child immigrants.

The Best Medicine

Pediatricians, including Craft and Shonkoff, assert that prevention is the best medicine for toxic stress. There is no better way to help children than by not separating them from their families, not locking them up in institutions, and not causing them any trauma. Pediatricians do not share the opinion that detention centers for migrant children must simply be made more comfortable: The institutional environment is harmful to children in and of itself and contravenes the best interests of the child irrespective of matters of cleanliness, nutrition, and so forth. Craft suggest that even a state program to rehabilitate children who have experienced toxic stress would not guarantee complete mental, emotional, and physical rehabilitation.

As part of the #CrossborderChildhood campaign, ADC Memorial calls for the development of new forms for regulating a child’s return to their country of origin and an end to the practice of placing migrant children in a closed facility for violators in both the country of migration and the country of origin. Children must be immediately returned to their own family, a foster family, or a special children’s center; the receiving country must be notified in advance of a child’s arrival, situation, and needs in regard to rehabilitation and education.

The special rights of migrant children are reflected in updated UN and CoE documents.

Patrycja Pompala

The Bibliography

- Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project, Charles H. Zenah, Charles A. Nelson, Nathan A. Fox, Anna T. Smyke, Peter Marshall, Susan W. Parker and Sebastian Koga

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/development-and-psychopathology/article/designing-research-to-study-the-effects-of-institutionalization-on-brain-and-behavioral-development-the-bucharest-early-intervention-project/3EFBD6B6D3F4E64512A961E488AED627 - The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress, Jack P. Shonkoff, Andrew S. Garner, https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/129/1/e232.long

- InBrief: The Science of Neglect

https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-the-science-of-neglect-video/ - Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: central role of the brain, Bruce S. McEwen

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181832/ - How detention causes long-term harm to children, Laura Santhanam https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/how-detention-causes-long-term-harm-to-children?fbclid=IwAR1pciekl5hbn_d39sgYYYY8blf23-y3NUfwXoR00NcSAXROMIbQj3JRX-c

- How the toxic stress of family separation can harm a child, Laura Santhanam

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/how-the-toxic-stress-of-family-separation-can-harm-a-child - ‘Why did you leave me?’ In new testimonies, migrants describe the ‘torment’ of child separation, Amna Nawaz, Gretchen Frazee, Rebecca Oh

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/why-did-you-leave-me-in-new-testimonies-migrants-describe-the-torment-of-child-separation - Migrant families ‘traumatized’ by Trump separation policy file lawsuit, Daniella Silva

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/traumatized-migrant-families-separated-trump-file-lawsuit-n1062146 - Detained migrant children suffer ‘trauma after trauma,’ say pediatric experts, Amna Nawaz

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/detained-migrant-children-suffer-trauma-after-trauma-say-pediatric-experts?fbclid=IwAR1-GdpmnxuG0j17_i1dO4bKzPh0X95x7-wmc5T8HzZGZDn8wDT_fSMkyi8 - ‘Can’t feel my heart:’ IG says separated kids traumatized by Colleen Long, Martha Mendoza, Garance Burke

https://apnews.com/63e7e47666914bf79eff7366e8eb411b?fbclid=IwAR0-ly7XBqawbdvbeAEcc5RKNpgO-0eI7SHmFXiwCwXS4kKg4zWwzeNoSA4

Feedback

Feedback