Exactly one year ago, ADC Memorial published the report “Romani Voices From Hell”, which was based completely on interviews with Romani people in occupied territories and Romani people who had become refugees and lost their homes.

In the year since the war started, the situation of Ukrainian Roma, who faced major difficulties even in peacetime, has turned into a catastrophe. The Russian invasion interfered with Ukraine’s nascent system for providing assistance to Roma, since the work of state and private charitable foundations was redirected to wartime needs. Thousands of Roma became refugees and encountered discrimination and social isolation in European countries. The only way for people who lived in Eastern Ukraine and found themselves in occupied territories right after the war started to save their lives was to travel to Russia, where they were forced to undergo the “filtration” procedure at the border and endure life in refugee centers. Many for whom Russia was merely a transit country had a difficult time leaving for European countries because of various problems with their identity documents.

Today, on April 8, International Romani Day, we are publishing a new report containing the accounts of Romani people and the volunteers who helped them about their lives after fleeing Ukraine.

The report is available in Ukrainian Рома з України: рік війни та біженства

The report is available in Romani Ррома андай Украйина: екх бэрш маримос тай нашымос

Stories of Roma from Mariupol as recounted by volunteers.

Since February 2022, over 100,000 Ukrainians of Romani origin have been forced to flee their homes. Romani families – mainly women with children – tried to leave Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Luhansk oblasts for other countries, but not all were successful. Many lacked documents and money, and others were simply not able to leave the captured territories in time and were subjected to forced evacuation to Russia.

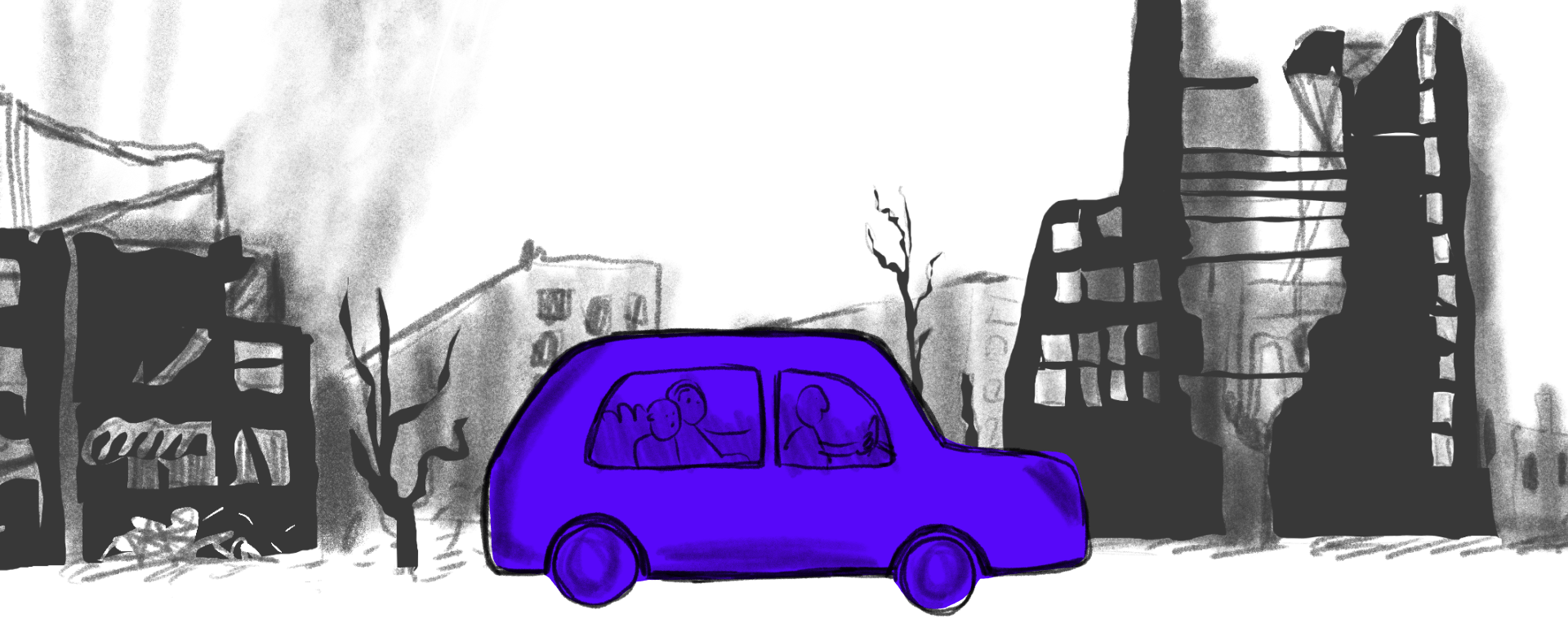

Some of the first to leave for Russia were residents of Mariupol, which was almost completely destroyed during fighting and unrelenting shelling.

A volunteer from St. Petersburg described the process of helping Romani refugees during the first days of the war:

“The first stream of refugees from Mariupol started arriving during the first days of March 2022. There were many Romani people among them. They all came through Taganrog. After that, some went to various refugee centers, while others made their way to the border on their own and went to Europe. The people who were in refugee centers and were not able to travel independently tried to contact volunteers and then travel to the border with their help. They generally did not stay long at the centers. They complained about terrible conditions and poor treatment by workers and other refugees. I can’t say that they were openly discriminated against, but the attitude toward them was biased and aggressive.

For example, several Romani families, a total of 58 people, at a refugee center outside of Shatura, Moscow Oblast, got in touch with us in March and asked for help arranging travel to the EU. It was very difficult to find transportation for such a large number of people, so we had to transport one group first and then the other. Since they were afraid to travel to Europe separately, we had to find a place for the first group to stay in St. Petersburg while waiting for the others. We had several people with large apartments in St. Petersburg, so that’s where we normally housed refugees.

Aside from this large group, small Romani families also came. We also often housed them with volunteers, since they needed time to recover after this major shock and the long journey. We had to help some people with their documents, because they were not all in order.”

Yanush Panchenko, an expert, researcher, and co-founder of the Ukrainian Centre of Romani Studies at KSU writes what Ukrainian and Russian Roma have traditionally had close ties, since the same ethnic groups live in both countries. In both Russia and Ukraine, Russian Roma, Calderari (Kotlyari), Chisinau Roma, Servitka, Vlachs, Crimean Roma, and Moldovan Roma are widely represented. They often intermarry, visit each other and travel from one country to another in search of a livelihood. There have been frequent cases when children have been born to Ukrainian Roma visiting Russia, thus they were documented with Russian birth certificates. After some time, these families would return to Ukraine and continue living there without paying much attention to what was written on their documents, since this never created complications for them in their daily lives. However, when the war started and Roma were forced to flee their homes, documents became a nearly insurmountable problem for many Roma.

“Every time we’ve had a request from a Roma family, we’ve had to carefully check and analyze all the information relating to their documents, especially their children’s birth certificates. Half of the children in one family could have Ukrainian birth certificates, while the other half could have Russian birth certificates. Because when a child was born, their family could have been living with relatives outside of Moscow or somewhere else in Russia, and the child could have been registered there and been issued a Russian birth certificate before the family returned to Ukraine. And then the family could have more children there, and those children would have Ukrainian birth certificates,” continued the volunteer from St. Petersburg.

“For example, we had a family of 15 from Mariupol. The reverse side of one of the children’s Russian birth certificates said that he was a Russian citizen. So he couldn’t leave Russia for Europe because he didn’t have a visa. After this case, we started carefully checking all their documents and asking for additional information, photos of the reverse sides of their birth certificates, and so on.

We have a pretty complex case right now, and we don’t know what to do. There is a Romani family from Mariupol – three children and their mother. The father has already left for Germany, and they’re following him. One child’s documents were all in order. The second had a Russian birth certificate, but it was written on there that both parents were Ukrainian citizens, so there shouldn’t be any problems with that. But somehow the third child’s birth certificate has a stamp saying he’s a Russian citizen. This was most likely some kind of mistake, but this mistake could cost us a huge amount of time, nerves, and money, because in these cases there is no procedure for renouncing citizenship. So we will probably have to prove in court that the document was stamped by mistake.”

Because Roma move frequently from one part of Ukraine to another, many of them were not living in the towns where they were officially registered when the war started. Since then, they have not had the chance to leave for areas controlled by Ukrainian troops and are now living under occupation. If a person trying to gain refugee status has a residence permit stamp in their passport for a city that is not under occupation, this makes it more difficult for them to cross into the EU, because European border guards will have doubts about this person’s true intentions. We know of families that lived for a long time in Mariupol, even though they were officially registered in Mykolaiv, which is under Ukrainian control.

“We have had several cases at the border crossing in Narva when they didn’t want to let Romani people through because of their registration. A family was traveling from Mariupol, but one of them had a residence permit for Mykolaiv, which is under Ukrainian control. This raised a lot of questions for the border guards. They didn’t believe that this person was telling the truth and was really a refugee. They could have said: ‘Okay, you and you, go ahead, but this one has to stay because he’s not registered in Mariupol.’ However, it’s clear that a person from a large family could be registered in one city and live in another, or that he was visiting when the war started. As far as I know, none of these cases have ended badly. Everyone was let through in the end. But these situations took up a lot of time and nerves for both the Roma and us. There was one case when a member of a Roma family was not let through in Narva. They decided they wouldn’t leave without him. They returned to the bridge and said that they would sit there until their relative was let through. In the end, he was let through several hours later.

In terms of Russian border guards, there have also been cases where people stood in line for seven or nine hours, or even for entire days. The guards asked them many questions when they were checking their documents and did everything very slowly. They would fixate on passport photographs or some other document. But everything worked out fine with the Roma that we helped leave.”

People could be denied the ability to cross the border because of other problems with documents: expired passports, outstanding debt, and so forth.

Below is the story of Roma from Mariupol who survived a long journey that ultimately ended in Germany. Russian border guards suspected that one of them had a forged passport and keep him at the police station for days. Their group contained 11 adults and 25 children, from infants to adolescents. This interview with Kristina D. was recorded in Narva, Estonia in June 2022:

“We are all from Mariupol. We are all Chisinau Romani. There were 36 of us with our children. We are all from Levoberezhny District. We lived there in our own homes in a village-like settlement. There were about 160 of us. We lived in dense conditions, one right next to the other. We lived well. We had our problems, but we generally didn’t complain. We didn’t believe there would be a war or bombing up until the very last minute. We heard on the news that Russia was about to attack, but we remained calm. At 4 a.m. on February 24, we heard detonations and understand that they had started bombing us. One shell fell on my grandmother’s house; it is far from us, but the explosion sounded like it was right next door. We grabbed the children in whatever we were wearing and ran to my brother’s apartment. All our relatives gathered there. He has an apartment with a basement, so we were more or less safe from the shelling there.

This was in the morning. Then very heavy shelling began in the neighborhood where we were. Everything outside was rumbling, and the earth was shuddering. We hid in the basement when it started. We spent a week and a half there. The shelling was almost constant during this time, so it was terrifying to go outside. Then, when everything calmed down a week and a half later, we made our way to Kirov Street. One day Ukrainian soldiers came to us and said, ‘Gather your things. We will take everyone out through the corridor, we are letting everyone out. Go to the drama theater.’ We gathered everything we could and went to the theater, but the soldiers there told us: ‘Turn back… Russia won’t let you through.’ The city was already blockaded at that time. Negotiators tried to organize a corridor several times so we could leave, but nothing went right and we were not allowed to leave. After yet another attempt, we went to the Savona movie theater, because people said there was a large shelter there. It was already dangerous for us to return to our house, and we didn’t even know if it was still in one piece. There were also refugees at the Savona. Many people were in basements. And they came out to us with shovels. They refused to let us in. Do you understand? And when another round of bombing started, we just ran for the Central Market. It was quite far away, but we had no other choice. We were left with our children under the open sky. Shells were flying, planes. Houses were burning down right in front of our eyes and human corpses were strewn everywhere. We ran with our children in terror and cried.

We found a nine-story house with a basement near the market. A lock was hanging on the door, but we broke it and went in there to live. We were there for a while. From there, our men ran two or three blocks under fire for water, because there wasn’t any in our building. Our neighbors, who cooked on the street, shared their food with us. We had a small supply of food with us: some grits and vegetable oil…

There was bombing almost every day. It started around 9 p.m. or 10 p.m. and ended at 5 a.m. Or it could be the opposite – everything was quiet at night and the rumbling began around 5 a.m. and ended only around noon.

At one point tanks entered our courtyard. We were terrified of the soldiers. We didn’t know who they were, we didn’t see them, because most of us were in the basement all day long. A couple of women would go out to prepare food, but shelling would start a minute later, and then we would all sit around again waiting for it to be quiet. One day our Ukrainian soldiers came and said: ‘Don’t close the door to the bunker. Always leave it open.’ We said: ‘How? We have lots of children.’ And they said: ‘Don’t close the door! Otherwise we’ll throw a grenade in here and that’s it. We won’t look to see if there are children.’ They said they wanted us to always leave the door open so that other people could run in quickly if necessary and save themselves from the shelling.

We lived like that for about two weeks. When we ran out of food and had nowhere to get it from, we decided to leave at our own risk, because we understood that we would be killed there. It was terrifying, because many people had already perished by that time. My aunt and my grandfather died. A shell fell on the neighboring basement, which was about 500 meters from us, and people died, including children. People were hit by bombs several times right in front of our eyes. The day before we left – March 16 – the shelling lasted all night. We left on the morning of March 17, and we were later told that a shell hit the nine-story building where we had been hiding. The drama theater was also shelled that day.

We left on our own, in our own cars, which were still intact. There were about 40 of us. There were six cars. They were all crammed with people. Other Roma left Mariupol with us. There was a total of about 150 people. We headed in the direction of Kerch. From there, we decided to make our way to Rostov, to our relatives. It was already impossible to head in the direction of Ukraine — there were Russian soldiers everywhere, and they only let people through in the direction of Russia.

We went through 27 Russian checkpoints from Melitopol to Crimea, to Dzhankoi. We were stopped at each one, and our cars and our persons were thoroughly searched. They look at the men particularly carefully: They forced them to undress and looked for marks from gun butts. We didn’t get any sense of particular dislike from the soldiers. They treated us normally, but it was still terrifying every time the soldiers approached the cars and forced us to get out and explain who we were, where we were going, and so on.

We arrived in Kerch at 1 a.m. We stopped there to rest. Some people noticed us. They saw that our cars had Ukrainian plates and offered to help us. It turned out they were some kind of officials. We were put up in a hotel, where we spent the night and were fed. In the morning we went on to Rostov. The administration even offered an escort to Rostov, but we refused because we would have had to wait a long time and we were scared that there would also be shooting in Kerch. That’s how we end up in Rostov. Our relatives took us in, and we lived there for almost two months. We were able to earn a bit of money there. We mainly worked in private gardens — digging and collecting trash for 100 rubles an hour. Then those who wanted to went on further. Some stayed in Rostov. Thirty-six of us decided to go to St. Petersburg and then on to the Baltics and then Germany. People said it was quieter there and you can earn a living. I have a son there. He went there and liked it. He said: ‘Mom, come here. It’s quiet, everything is good, people are treated normally.’ And in Russia we won’t be able to earn a normal living. We earned enough only for the trip, for tickets. We won’t survive here. We won’t be officially hired because we are Roma. We have a lot of kids. You have to pay an insane amount of money for housing.”

When leaving [Russia] for Estonia, Kristina D.’s cousin Nikolai was held by Russian border guards for 24 hours, and the entire group had to wait for him: “He supposedly had a counterfeit passport. The stamp was faded or couldn’t be seen. But all of our documents are originals. We all have identification numbers. We all have a set of documents. We received benefits at home – we would not have been able to without these documents. We were registered with social services. Even the mayor of the city knew us. No one ever picked on us. And all those checkpoints we went through! No one every showed any suspicion of us. So we waited while they checked his information and issued a decision. We asked the Russian border guards: ‘Tell us, should we wait for him on the other side or not.’ And they said: ‘Well, they won’t shoot him, but they will put him in jail.’ ”

Nikolay crossed the border the next day. He said that he spent the night in the police precinct without food or water and that he was subjected to physical violence during his interrogation. His relatives waited for him in Riga. With the help of the volunteer group Friends of Mariupol, they all reached Liepāja together and then crossed by ferry to Germany. They had to spend the first two weeks on the street in Travemünde before they could be placed in a refugee camp.

According to an advocacy group of volunteers in St. Peterburg, fewer and fewer refugees are now coming to them for help, and even fewer are coming to the city at all.

“Today very few people are coming to the city and asking for help. The largest number of requests relate to medical care. Since there are no medical facilities in Mariupol aside from the hospital, which is packed with the wounded, people have nowhere to go for treatment. This is a huge problem for people with chronic illnesses who just don’t know what to do. People also come to us for help reuniting with their families. There are Roma whose families we sent to the EU but are themselves Russian citizens. These people don’t have any legal way to leave Russia right now. They need to wait until their relatives return or become naturalized in the EU, and then they can submit documents for family reunification to the embassy and wait for a humanitarian visa.”

Roma from Kherson – the second wave of refugees

Panic set in in Kherson in mid-August, right before the Russian troops left. Residents of the city and nearby localities, including Romani people, feared that there would be battles in the city, so many decided to leave. Since the roads out of the city and into Ukraine were blocked off by Russian occupation forces, the only direction people could go was toward Russia; many hoped to reach European countries from there. The difference with the wave of refugees from Kherson was that most of them left on their own, in their own cars. The simplest option for them in both logistical and technical terms was to go to St. Petersburg and then cross the border into Estonia or Finland. However, without knowing the geography or having any contact with volunteers, most of the refugees drove to what seemed to be the closest border – the Latvian border. For this reason, at one point a fairly large and unmanageable number of refugees from Kherson were at this border:

“Since Kherson and other cities in the region did not see the kind of fighting and bombing that places like Mariupol did, many residents left in their own cars. They just crossed the border and set the GPS for the fastest route to Europe. This is how they all found themselves at the same checkpoint in Shumilkino, Pskov Oblast, since it was the easiest to pass through. This created terrible traffic jams. There were several days when there were almost 1,500 cars there. And the neighboring checkpoint, which was 6070 km away, could have been empty. But no one knew about this. This traffic jam was cleared with the help of volunteers, who went to the border, fed people, and explained where they could cross faster.

If people were traveling without a car, they generally initially ended up at the Taganrog refugee center. Large Roma families generally came to us for help after being sent from Taganrog to a region – to Shatura, Kaluga, outside Voronezh, Belgorod, etc. They usually took an evacuation train to these regions. From there, they usually took other trains to reach St. Petersburg.”

A Romani man who lived with his family outside of Kherson recalls the following about what they faced on their journey from Ukraine to Europe:

“The situation in the city was worsening. Explosions in the city were increasing in frequency; there were more Russian soldiers. In the spring, for example, there weren’t very many of them, and we hardly ever saw them. But by the summer, all the districts and streets were flooded with soldiers. On May 9, the occupation authorities reached the Roma youth center, which I was the director of. Before the holiday celebrations, the soldiers checked all the buildings whose windows opened out onto the main street and looked to see what was inside. They came here early in the morning on May 9. They started to look for the owner, but they couldn’t find anyone, so they just broke down the door. They didn’t initially seem to have much interest in the building, but in June, they started using it for their own needs.

This whole situation made me very nervous. I didn’t feel safe because there had been cases where my acquaintances – civilians – were taken prisoner. Like me, some of them went to demonstrations against the occupation and were activists; others were taken prisoner by chance, for no real reason. On top of all this, they started bombing us heavily. We started spending more and more time in the cellar. We hid for several hours almost every day. This was unbelievably demoralizing. It became intolerable when all my friends and acquaintances left. Those last days, when I was sitting in the cellar, I often thought about why I hadn’t left yet and what the purpose of my staying was. So one day my mother and I decided to leave along with my friend and his mother.

I started carefully preparing to cross the border, because I had heard a lot of stories about how thoroughly they checked everyone and about how they didn’t let some people through. But others went through without any problem. Naturally, I started preparing for the most complicated option. I bought a new phone so that it would be harder to restore my messages in messenger apps, I deleted any provocative posts I had made on social media and then deleted the apps themselves, and so on. When everything was ready, we left.

We decided to go through Crimea, since this was the safest and shortest way to Russia. We went through several Russian checkpoints along the way. At one of them right before we reached Crimea, a soldier in an LPR cap ran out to meet us. He was drunk or hungover, and he had an automatic weapon. He was extremely aggressive with us, which was terrifying. He kept screaming at us, saying that we were standing in the wrong place, that we were being insolent, and other things. I pulled over to where he indicated, and he started checking our things. I tried to speak calmly with him so he didn’t get nervous, and shortly thereafter he started to make excuses for his behavior, saying that soldiers in armored vehicles often used this road and would just run anyone who wasn’t attentive off of it.

We reached the border after finishing the check. There were only several cars, and the line moved quickly.

Everyone goes through filtration at the border. A separate camp is set up for people who are entering Crimea for the first time. They say people who have travelled there more than once do not get sent to the camp, but I don’t know if that’s true or not. There were offices for interviews on the territory of the camp. The friend I was traveling with and I were interviewed in one of these offices.

Since I was getting ready to cross the border, I thought it would be morally easy for me to speak with the Russian border guards. But once they started speaking with me, I had a hard time remaining calm. They’re not rude, they don’t scream, but the emotional pressure that emanates from them is very strong. You try to answer every question in a way that doesn’t give them any reason to ask you another question on the same topic, but the longer the conversation goes on, the harder it becomes to tie what you already said to the new questions, because your brain turns to mush and you can easily forget what you have already said from the tremendous nervous tension.

Thankfully, they didn’t ask me about my political position or my thoughts about Putin and the war. They asked where I was going, why, and so on. But after the border guard checked my passport, he entered my information into his phone and found out about elements of my biography – everywhere I’d worked, where I lived, and so on. I was most worried that they would find my social media accounts, since I had shared many anti-Putin posts and because my brother serves in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, just like several of my friends. And right then the border guard asked if any of my friends or family members were serving in the Ukrainian Army. I said I didn’t know, because everything was changing so rapidly and someone could leave for the service. Fortunately, he stopped asking me about that and said that I should give him my phone and wait outside. At first I started to feel better, but then I suddenly remembered that I had not deleted many compromising things from social media and that if he spent a little time looking, he would find posts proving that my friends and relatives had ties to the Ukrainian Armed Forces and posts proving my obviously anti-Putin position.

They interviewed my friend during this time. But they asked him more direct questions. For example, they asked him what he thought about the special military operation, why he was leaving, and so on.

I waited about an hour after the interview. I don’t know if they checked my phone. During this time, I was preparing myself for the news that I wouldn’t be let through or that I would be sent for another interview. But a man came out, read out my last name, and gave me back my passport and phone. I asked if I could go, but this person just looked silently at me and didn’t respond. I asked the question several times, but he just kept looking at me. Then I decided to go over to my car. Thankfully, no one stopped me.

We drove on. First to Dzhankoi, and then to Yevpatoriya, where we spent the night. Then we drove to our relatives in Rostov Oblast, then from Moscow to Pskov Oblast and finally on to the border with Latvia. The trip took a total of four days. No incidents happened the entire time. We weren’t even stopped by the police once.

We spent almost 40 hours at the Russian border. This was the longest it has ever taken me to cross a border. Even though the line wasn’t long and cars with European and Russian plates were let through very quickly, cars with Ukrainian plates were sent to a separate line, where they were kept waiting for several dozen hours. Everyone in the line was from Kherson, Donetsk, or Luhansk oblasts. After about 30 hours, we drove up to the checkpoint. That was when I understood why we had waited so long. They just took our documents from us and then absolutely nothing else happened for 10 hours. Our documents were just lying there on the table, and no one was looking at them. Then the shift changed, and that was when a woman from the new shift picked up our passports and started checking them. That also took longer than usual.

A car ahead of us was carrying a young Ukrainian family from Donetsk Oblast – a father, a mother, and a one-year-old child. They told us how hard it had been to get through the Russian checkpoints in Donetsk Oblast. They were searched and questioned extensively at each checkpoint. People were fingerprinted and so on. He was driving toward Kherson Oblast, but then, like us, he entered Russia through Crimea. In the end, when he was going through the checkpoint on the Russian border to enter Latvia, he was not allowed through because the border guards didn’t like how his photo was pasted into his passport. They told him to go back home to Donetsk Oblast to redo his passport, and only then would they let him through. But the problem was that his city was under occupation and he had no way of redoing his passport there. So he was in very low spirits and didn’t know what to do next.

We went right after him, and I thought that if one of us wasn’t let through, we would all have to turn around and go who knows where. But everything worked out and we made it to Latvia.”

What is happening in occupied territories

Roma who were not able to leave the occupied territories faced the same problems as many other Ukrainians: violence, theft, shortages of food and goods, and the mortal dangers of wartime. One Romani man who was granted refugee status in a European country described the situation as follows:

“We sometimes get news from home. When we left, I asked my acquaintance to live at our house. Everything was normal at first. But one day Russian soldiers came to him looking for a place to live. They told him directly that they wanted to occupy the home. He responded that he couldn’t leave it. This was before the liberation of Kherson, and the city was being evacuated at the time. So they told him he would have to evacuate whether he wanted to or not and that they had a lot of mobilized soldiers that needed a place to live. They went away after that, and my friend wasn’t planning on leaving. But during the next round of shelling, a bomb flew into the house next door, and my friend decided to leave after all. In just half an hour, he had gathered up his things, given the keys to the neighbors, and set off for Crimea.

In the winter, our neighbors wrote that soldiers had broken down the door to our house and started living there. This was a huge blow to us, even though we understood that it could happen sooner or later.

We asked our relative to go find out what exactly was happening there. When he walked into the courtyard, he saw two young Russian women sitting in the kitchen; there were no soldiers there. He told them he was looking after the house and asked who gave them permission to live there and how long they had been there. They didn’t answer these questions, but said that the house was very cold and asked how to turn on the electricity, water, gas, and heater. Then they said that they really liked our house because it looked like the houses their husbands lived in in Chechnya. That’s how my relative found out that these were the wives of Kadyrovites. The conversation ended there. Our relative just asked them to tell the neighbors when they were leaving, and then he left himself.

A couple days later, our neighbor called us and said that she had seen soldiers near our house complaining that it was very cold inside, that there was no way to turn on the water or gas, and that it was impossible to live there and they needed to find another place. They spent another two days there and left, leaving the door broken. It was just hanging wide open for three days. Then the neighbors welded it closed at our request, and everything has been quiet there now for several months.

It’s unclear what the situation in the city is right now. There are shortages of everything; it’s very hard to make ends meet. Food products have become very expensive. Plus, your life is constantly at risk, if not from soldiers, then from bombs.

When I left, I really hoped that in a year, in the summer, everything would end and that my city would be liberated and I could return home. There’s not much time left until summer now, and I really doubt that my dream will come true. But my dream is to return somehow or other, sooner or later. I hope the war will end and I will return to a liberated Ukraine. If my city remains under occupation, then I definitely can’t return home because it’s too dangerous. Everyone knows me, and no one will let me stay alive there. And I myself wouldn’t want to return to an area controlled by Russia.”

Different experiences in EU countries

Most Romani people who fled to European countries have not received the protection they expected and have had to deal with local bureaucracies and discriminatory treatment. The situation for Roma refugees from Ukraine is most difficult in Eastern European countries. European human rights defenders have repeatedly drawn attention to discrimination against Roma people in refugee centers, denials of humanitarian and medical aid, and problems applying for refugee status.

In one case, the mayor of Przemyśl, a Polish city right on the border with Ukraine, banned the assistance center from accepting Romani refugees. Volunteers helping refugees told ADC Memorial that on June 26, 2022, a large group of refugees, including about 100 Roma, had accumulated at Przemyśl’s train station because of disruptions in the schedule of arrivals and departures. Mayor Wojciech Bakun, who was at the train station, told volunteers that they must not take Roma to the assistance center at Tesco, even just to spend the night.

“The mayor kept watch at the station all night, making sure that we didn’t take any Roma to the assistance center at Tesco, even though we had over 400 free beds. Even just to sleep for a couple of hours. At the same time, right in front of my eyes, almost 50 Romani children and their parents were forced to sleep on the platform, right on the pavement surrounding the station. He even sent away the taxis we wanted to use to take them to the center and told our volunteers they couldn’t help them. After that, the mayor came to the center. He was looking for me, threatening to arrest and deport me, even though the only thing I’d done was put five Roma in a car so a volunteer could drive them to the center to spend the night. Some of the family was already with us, one child had a heart problem,” recounted a member of a group of volunteers helping refugees.

Roma from Ukraine often encounter intolerance and xenophobia in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Moldova and other countries. For this reason, many Roma who fled the war gradually started returning home in the summer. But the escalation from the Russian Army’s mass shelling of Ukrainian cities has again forced Roma to flee to European countries.

On October 30, 2022, volunteers from Przemyśl told ADC Memorial that the situation with refugees deteriorated right after the Russian Air Force launched full-blown missile strikes at critical infrastructure in Ukraine. This was particularly difficult for Romani people, because they were denied entry to large humanitarian centers and assistance:

“After Ukrainian cities started coming under mass shelling, the flow of refugees increased again, and we are currently stretched very thin. Our shelters aren’t managing. There are always up 30 refugees in our tent alone, even though it is meant for 18-19 people. All the Roma usually come to us, since they are denied spots at Tesco (a humanitarian aid center in Przemyśl) and other large centers. They aren’t even taken into the room for mothers and children at the train station – supposedly there’s no space there.

Sometimes a Romani family that has just crossed the border will come to us. We need to put them somewhere. We call Tesco and ask if they have space for a refugee family. If they say that they do, then we agree that we will send them right over. But as soon as we bring them and the Red Cross workers see that they are Roma, they immediately turn them away and the police accuse the volunteers of bringing the Roma. They don’t even look at whether the Roma are poor or not. For them, Roma are Roma: If you’re a Romani person, then we won’t take you. Roma aren’t given any humanitarian aid, either – not warm items or food. They are just turned around and told to wait for transportation so they can go to another place.

If they’re lucky, they can take a Hanover train. If not, they stay here, and we try to place them in private shelters or tents. We don’t have that many problems now, when it’s not cold yet, but I don’t know how we will survive in the winter. All the private centers rely exclusively on donations and the personal initiative of volunteers. Right now we’re already having trouble finding money for generators and heating for the tents. We only turn them on at night to at least save a little. Their output won’t be enough in the winter, and the refugees, including the Roma, of which we have many, will simply freeze. Many of them don’t even have warm clothing, and no one besides us will provide them with it.”

Another volunteer from Poland told us that the Roma who were turned away from Tesco had to wait for a train to Hanover for several days: This was the only free option to leave Poland for Western Europe, but Roma were either denied seats on the train or put in a separate car where there were no other refugees besides them. While waiting for the train, many of them had nowhere to sleep; they tried to make a place to sleep in the train station, but the guards drove them out of there.

However, there are positive examples in spite of the multiple instances of xenophobia and intolerance of Roma in European countries. A Roma man from Kherson describes his experience in refugee camps as follows:

“After Latvia, we went to Poland and then on to Germany. We registered at a refugee camp in Berlin. We were there for two days and were then sent to a different camp in Giessen. It was absolutely terrible there. It was very dirty and messy. There was trash everywhere. We simply couldn’t live there and decided to leave, even though the administration said we couldn’t. They said that we were already registered with them, that we had been fingerprinted and could only be there. Still, we decided to risk it and, following our relatives’ advice, we went to Hamburg. From there, we ended up at the camp in Boostedt. This was a very nice camp, where half of the residents were Ukrainian Roma: Servitka, Vlachs, Kishinyovtsi, and Kalderash, mainly from Kherson and Mykolaiv oblasts. This was a great joy for us, because we knew almost all of them personally; we constantly visited each other, talked, went into town together, and so on.

My mother and I had a separate room in the camp, and the camp in general was very clean and well-kept. My mother even got a part-time job in the laundry room. We hoped that we would be left there permanently and not moved anywhere else, because we were all happy with it. But three weeks later, we were told that a new group of refugees was coming and we would be moved to another camp.

After we left, that camp only had Romani people. Now I think that maybe the camp administration didn’t understand that we were Roma, so they decided to send us to a different camp. In any case, the day after we left, a large group of our relatives arrived there, and the camp didn’t have any trouble finding space for them.

From there, we were sent to Bochum, to an assessment center, where people were registered and sent to different camps. This was in October. I was very sick, my temperature was almost 40 degrees [centigrade]. The center was a real mess, we had to wait several hours in line. We ended up standing on the street until 4 a.m. Then we were registered and sent to Paderborn, which is 60 km from Bochum. The camp there was also very good, even better than in Boostedt. But there were hardly any Roma there – literally only four families: one from Donetsk Oblast, a Crimean Roma family from Mykolaiv Oblast, and two families of Lovari Roma. We spent a month there.

After a month of living in that camp, we were given a little house in the village of Beverungen. This is a remote locality without any telecommunications or internet connection. This was a disaster for me, because I needed to work, and its almost impossible to do that without the internet. The nearest store was 10 km from the house. The house itself was in terrible condition – everything was covered with mold and the living conditions were not normal. We lived there another month, and then we rented our own housing in November; we are still living there. I receive a stipend, my mother gets a pension and welfare benefits, which cover half of our rent. We exist on those funds.”

A Roma family from Mariupol that spent almost a week living in their cellar under constant shelling in March 2022, was forced to flee to Europe twice. In the first month of the war, they had to leave their home and make their way out of the city, which was almost completely decimated. Later in the fall, after they returned to Ukraine, they had to flee again, this time to Norway:

“My name is Artur. I’m a Romani from Mariupol. Before the war, I went to school. I did Greco-Roman wrestling for six years and attend a musical school, where I learned how to play the accordion.

Our family lived very well before the war. We had our own body shop and raised livestock. We never complained about anything at all, but on February 24, the war started, and all of that was destroyed. The body shop burned down, the farm burned down.

Last March, when there was fighting in Mariupol, my mother and I fled to the Czech Republic with other relatives. We lived there for four months. It was very difficult and dangerous to leave Mariupol. We first wanted to leave on March 26, when our neighborhood started coming under heavy bombed and there were gunfights in the streets. We wanted to head to Zaporizhzhia, but the Russian military checkpoint didn’t let us through. We returned and spent several days at home. We were able to leave the city on our second attempt, but we came under artillery shelling. We somehow made it to Zaporizhzhia and then on to Dnipro and, from there, to the Czech Republic.

We were safe there, but we all felt that we were not being treated as well as the Ukrainians. For example, at one point they refused to pay Mom her benefits, even though they continued to pay them out to other refugees from Ukraine. Almost no one made friends with me at the Czech school, even though they treated other Ukrainian children normally. Because of all these difficulties, and also because I really missed my father, we decided to return to Ukraine. When the Russian troops started to retreat and it became more or less safe, we decided to go to my father in Kyiv. We spent four months there. Later, when the mass missile strikes against Ukrainian cities started and Kyiv also started being bombed, my Dad got very scared and decided to send us abroad again. At first, we ended up in the Czech Republic again, where our friends live. We spent five days with them and then left in a car for Norway, where our grandparents were.

We are now in a place called Sunndalsøra. We were placed in a small hotel along with other Ukrainians and given rooms. Our family, for example, has five people, and we were given a five-room suite. The local residents here – mainly Arabs and migrants from other countries – help us a bit. For example, there’s a man named Marlan. He helped us collect basic necessities and clothes. And there’s another Kyrgyz man named Yakov. He gave us a table and chairs.

I don’t go to school here. I’m still attending my school in Kyiv online. I went there when we lived in Kyiv. I also study English, math, and Ukrainian with a tutor online.”