ADC Memorial issued a number of publications about the genocide of Roma by Nazis in Germany and the occupied countries in 1939-1945: a brochure was published, with the unique testimonies of survivers Roma of the Russian Northwest; video recordings of our conversations with Roma elders were included in the film “Personal Pages of the War History” (directed by Tatiana Chistova).

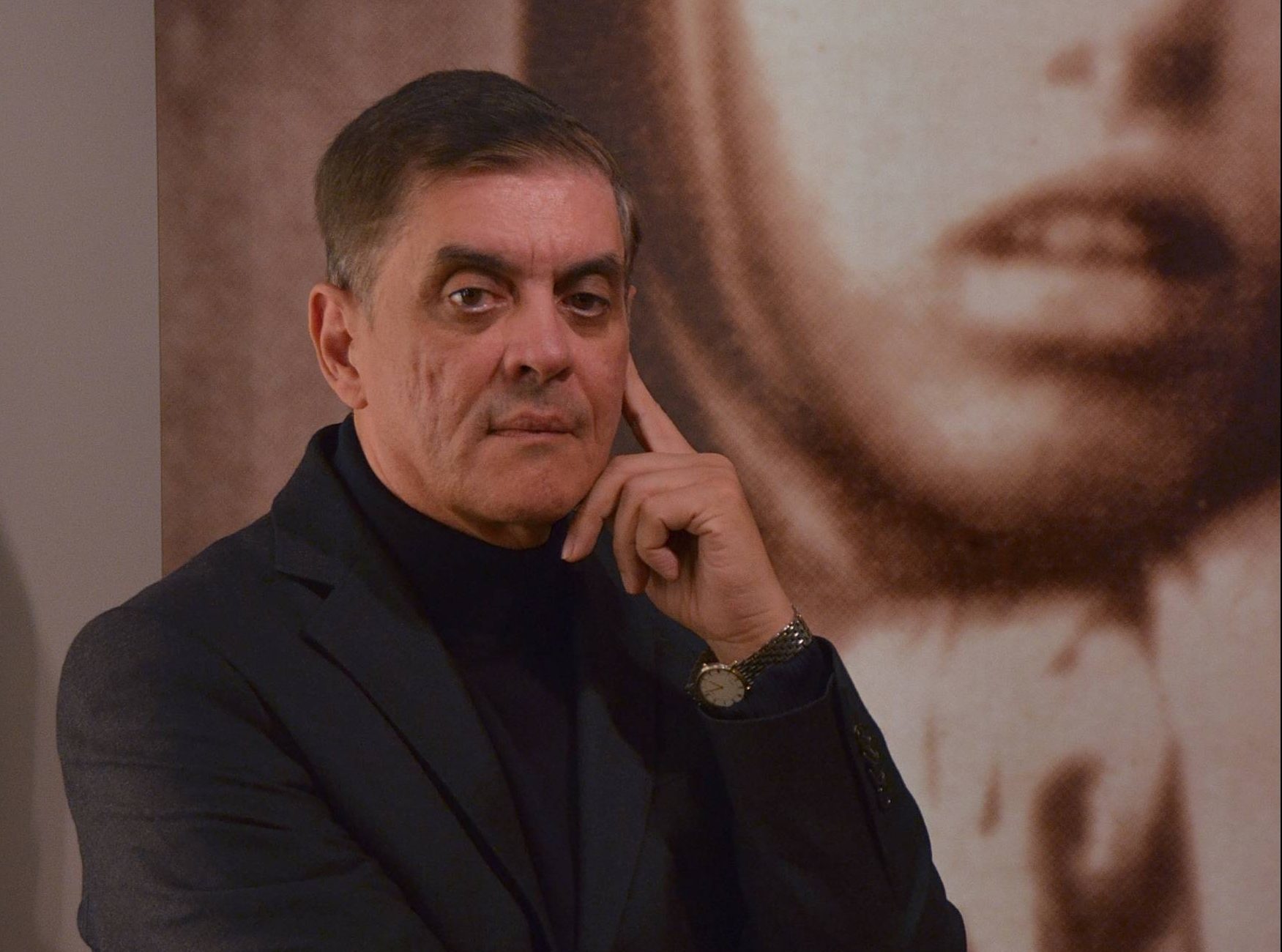

Despite the decades that have passed, this topic remains quite low-covered and insufficiently studied. That makes all the available evidences and all the attempts to preserve the memory more valuable. An important role in it has been played by Romani Rose, a Roma activist from Germany, the Chairman of the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma. ADC Memorial publishes an interview with him, kindly provided by Maxim Brisker.

Mr. Rose, tell me of your family please, what it was like? Who were your father and mother, and your other relatives?

I grew up in the shadow of Auschwitz. 13 of my relatives were murdered in the Holocaust: My grandfather in Auschwitz, my grandmother in Ravensbrück concentration camp, my aunt in Bergen-Belsen. My uncle and father, Vinzenz and Oskar Rose, survived the barbarity of the Nazis. The stories of these two, but especially their civil rights commitment to our minority in the young Federal Republic, had a strong personal impact on me. They were the first to file criminal charges against many perpetrators of the Holocaust against Sinti and Roma shortly after the war – at that time still unsuccessfully. My mother was not a member of the minority and during the war hid my father, who lived underground, my uncle, whom my mother and father had helped to escape from the concentration camp in Neckarelz together, and other relatives in her house in Heidelberg. For her courage, she was awarded the Federal Cross of Merit in the 1980s and her grave was recently given the status of a grave of honor by the city of Heidelberg.

You tell in many interviews of 500 000 of Roma people who disappeared in Holocaust, and among them were 13 of your relatives. You are the head of Roma and Sinti Council. What can you advise young Roma and other young people about remembering the Holocaust and the importance of this memory?

I would like to start by saying one thing first: Remembering the Holocaust is not about transferring guilt to the generation living today, but about taking responsibility together for our country, for our democracy and the rule of law. I would like to advise younger activists in particular not to isolate themselves, but to join forces. The successes of our civil rights work to date have only been possible because Sinti and Roma have worked together with people from the majority society.

In the interview with Roma Education Fund you say it’s not enough to be educated and continue with a good job etc. One must be vocal about one’s background as Roma. Is it still a problem for young Roma to openly declare their roots?

For many members of our minority, regardless of age, publicly professing their identity is still a problem. They fear negative consequences in their professional and private lives. Numerous studies show that this fear is not unfounded, because Sinti and Roma are the minority that still faces the most rejection. However, I would also like to emphasize clearly: creating the conditions for Sinti and Roma to participate equally in social life without being confronted with disadvantages because they profess their cultural identity is not a task for the minority alone, but a challenge for society as a whole.

Until 1982 you were not a Roma activist. How it happened that you became the most known speaker for Roma rights in Europe?

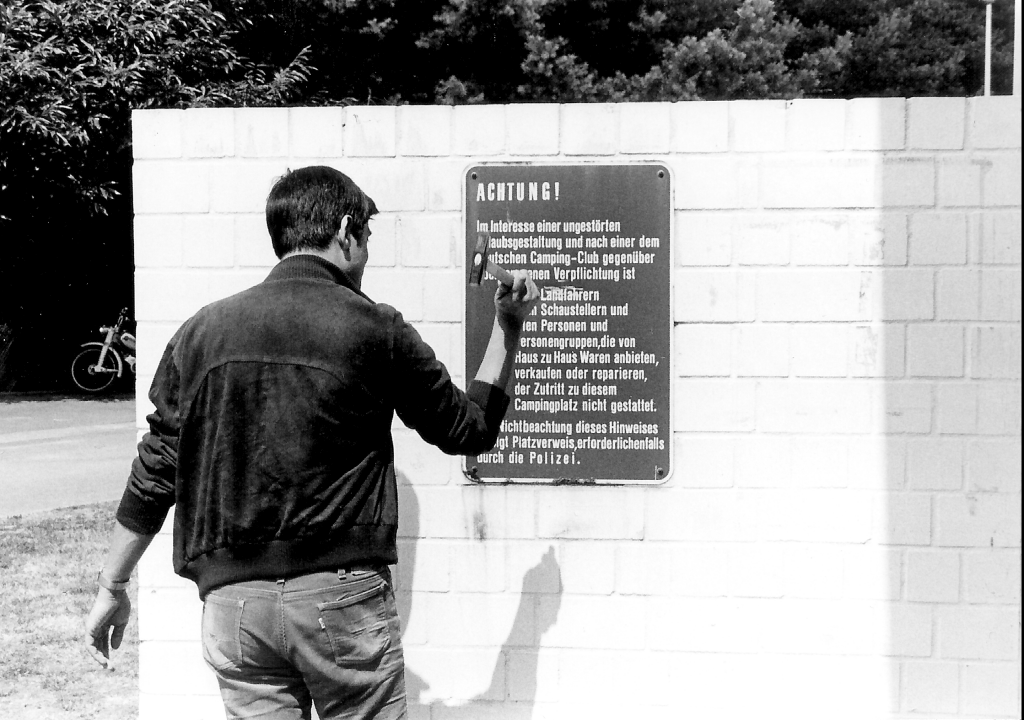

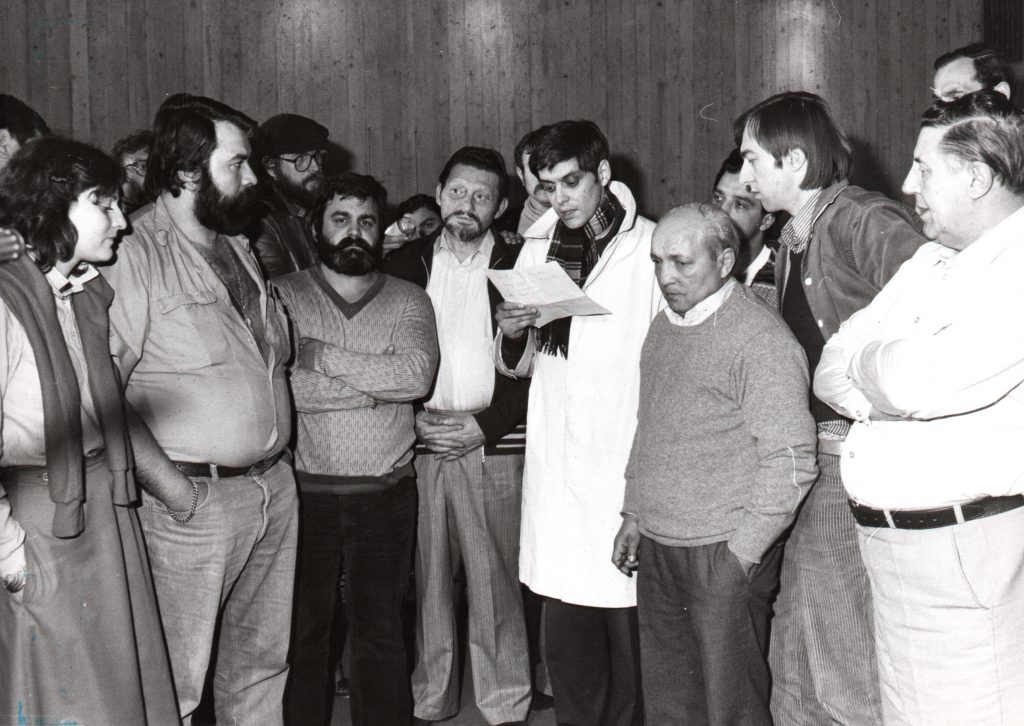

I had also been working for the rights of the minority before 1982; however, 1982 was the year in which the then Chancellor Helmut Schmidt first recognized the Holocaust of the Sinti and Roma, i.e. the murder of 500,000 people by the Nazis for racial reasons, for the Federal Republic. This success of our civil rights work was indeed a turning point and the direct result of the hunger strike that we – 11 activists, among them five Holocaust survivors – had organized at the memorial site of the former concentration camp Dachau at Easter 1980. At that time we succeeded for the first time in generating a broad international media echo for our cause.

As a young man, I too kept silent about my identity as a Sinto. For the same reasons that far too many still do today: after the end of National Socialist rule, there was a continuity of antiziganism, hatred, exclusion and discrimination. This “having to remain silent” in order to have an equal place in society hurt me deeply at the time, but was also a reason why I decided to become active in the civil rights movement in the 1970s. We were inspired at the time by the African-American civil rights movement and its icons like Martin Luther King.

You really did a lot for Roma to be recognized, concerning the Holocaust memory and concerning their identity recognition, what else remains that you feel is important to do right now?

Prejudices and clichés handed down over centuries still shape the image of our minority today. These clichés are transported by the media, which bear a special social responsibility. Filmmakers, as well as journalists, photographers and other opinion makers, directly shape the image that the majority of the population has of members of our minority through their work. In recent years, we have had tough disputes with media institutions, television stations and newspapers, which often still show little historical awareness of the antiziganism anchored in our society. However, many reactions of especially younger people to racist TV programs on German television in recent months make me hopeful. This commitment deserves our recognition and support.

However, positive counter-images to stereotypes in the media are still the exception today. We must therefore support young Sinti and Roma in particular and thus strengthen the visibility of our minority in society. When young, professionally successful members of our minority take on a role model function in public, they send a clear signal that Sinti and Roma are a natural part of German society. They counter the centuries-old, stereotype-laden portrayals of Sinti and Roma with positive images and thus encourage others to step out of anonymity.

There are about 10 million Roma in Europe. It’s hard to count sometimes. What can be done to unite them in attempt to be recognized? Should they be more united or is there another way for each community?

We work well with our partners across Europe, there is a fruitful cross-national exchange, joint projects and cooperation. We can learn from each other and support each other in our work. It is important not to isolate ourselves, but to work together, seeking solidarity also with members of the majority society and other minorities. This diversity is precisely what advances the civil rights work of Sinti and Roma in their respective home countries. The fact that Sinti and Roma are not recorded and counted as relatives has a good reason, by the way: the National Socialists, with the active support of both the Catholic and Protestant churches in Germany, which opened their church records, created genealogies and thus prepared the ground for the eventual extermination of 500,000 people. Rightly, such a registration is now against international law and is no longer practiced.

Did you meet Roma in other European countries and in Russia? What can you say of them?

Over the past decades, we have had numerous contacts and meetings with Roma throughout Europe, but especially in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Their situation is often still shameful. They are systematically excluded and marginalized in all areas of public life, from school to business. Equal opportunities and equal rights are still denied to them. This system of apartheid is a disgrace for Europe. However, it is difficult to make a general statement here, because the situation in the individual countries is very different.

You as a head of German Roma succeeded in many things. What do you think of other Roma communities and of their success or failures? What can they learn from you and the organization you lead?

The successes of the civil rights work of the German Sinti and Roma are indeed exemplary for Europe. But also the behavior of the Federal Government is a great example for the other European governments in terms of reappraisal and remembrance. We, the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma together with the Manfred Lautenschläger Foundation, have just awarded the European Civil Rights Prize of the Sinti and Roma to Chancellor Angela Merkel for her services to the minority during her term in office. We have had a memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe murdered under National Socialism in direct sight of the Reichstag building, the seat of the German Parliament, since 2012 and have been recognized as a national minority since 1997. We were only able to achieve all of this by working persistently with supporters from the majority society, but also with the support of other minorities, such as the Central Council of Jews in Germany, to change the way politics and society think.

In the interview with the Holocaust Remembrance Alliance you compared hatred of Roma with Antisemitism and added that it is deeply rooted in Europeans. What’s the best solution to eliminate this bias and hate of Roma?

Antiziganism, just like anti-Semitism, is unfortunately widespread in society. There is always the experience that the old stereotypes are carried anew into society. The equal participation of Sinti and Roma must finally be made possible in all authorities, in the police and in public life in general. To this end, antiziganism must be recognized and outlawed, just like anti-Semitism. The IHRA’s working definition on antiziganism is an effective tool for this. What we need are binding and legally secure rules and laws. In addition, we need positive counter-images to the existing negative images and stereotypes. Education is a key to this, but we must also encourage the members of our minority to step out into the public with their identity in a self-confident manner.

Your uncle made the Roma memorial in Auschwitz and funded it from his own means. It was a very significant measure. As for now, what do you think, should people do like this or is it a state that should it?

The Federal Republic of Germany has recognized the Holocaust against the Sinti and Roma, and so it is naturally logical that it is the responsibility of the Federal Republic to ensure that it is commemorated in a dignified manner. I would like to emphasize here once again what I said at the beginning: today’s Federal Republic and its political representatives bear no guilt for the terrible events during the Nazi era, but they do have a responsibility. The Memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe murdered under National Socialism in Berlin, which was opened in 2012 in the immediate vicinity of the Reichstag building in the presence of the German Chancellor, is a visible sign that Germany is facing up to this responsibility. When my uncle erected the memorial at the former Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp at his own expense in the 1970s, there was no widespread knowledge, either in the Federal Republic or in any other country in the world, that the Holocaust had taken place against 500,000 Sinti and Roma and that Sinti and Roma were murdered for the same racist reasons as the Jews. The monument that my uncle erected was an important milestone on the way to making the fate of the Sinti and Roma visible to the public during the Nazi era. From that point of view, it was the only possible step to achieve attention at that time. Today, however, knowledge about the Holocaust and the continued discrimination against the Sinti and Roma in Europe is so great that governments are increasingly anchoring remembrance in the public consciousness and it is thus also clearly their responsibility to ensure dignified remembrance and commemoration in their countries.

You wrote several very important books of Roma in Europe and their very hard fate. Do you write a new book? What’s the topic of it, if yes?

I am currently writing my biography, which is expected to be published in the fall. My professional life, as well as my personal life, are very closely tied to the history of civil rights work. I will look back at what we have achieved politically, but also look forward and address what still needs to be done.

Maxim Brisquer

Feedback

Feedback