The creative work of feminist artists has become the subject of investigations by various forces—aggressive women-haters, opportunistic politicians, nationalist activists, religious figures, and criminal courts—and is viewed by these connoisseurs of the arts as (circle what applies) “depravity – indecency – pornography – mockery of our national culture / traditional values – an affront to national / religious / other pro-Putin sensibilities.” The result of this attention from such concerned viewers has been various persecutions of female artists, from online bullying and a thorough thrashing in the press to criminal charges and the real threat of physical violence.

Russian and global human rights organizations have asked Russia’s prosecutor general to put an end to the persecution of the artist and activist Yulia Tsvetkova for body-positive “artistic portrayal of the female anatomy dedicated to the openly stated goal of celebrating the beauty of the female body.” The obvious fact that “Living women have…” periods, body hair, gray hair, and so forth (this is how Tsvetkova signed her drawings, and it was also the name of an exhibition put on by other female artists to support her, which was organized by Katrin Nenasheva, who was recently re-arrested) is so offensive to Russia’s repressive system that Tsvetkova faces a criminal sentence of up to six years for “pornography.” “And how would the people persecuting Tsvetkova know that images of the vagina have long hung in museums? This means that we must educate people, organize virtual exhibitions and lectures,” said the female artist Aidan Salahova, who started a flash mob in support of Tsvetkova in 2020. And she has a point: How would they know?…

Real women have… body hair, menstruation, fat, wrinkles and graying, imperfect skin, muscles, and that’s ok!

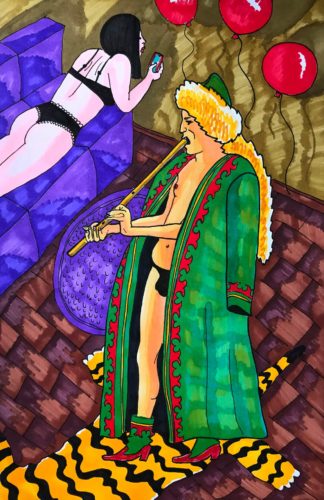

Some viewers of the work of Tajik artist Marifat Davlatova rejected her work, and not just because the models were nude; they also had an aggressive reaction to the national flavor of her paintings: “I had an exhibition devoted to women in Dushanbe in August 2018. I wanted to show the beauty of the female body, the female soul as a protest against harassment on the streets, violence, and stereotypes. I portrayed women in national costumes. There was a positive reaction, but also negative criticism along the lines of ‘this girl is sick, she didn’t get married and is enraged that her parents allowed this’ and ‘things like this cannot be created in our society, girls cannot do that.’ There were also verbal threats (that I should be burned and hung), including from women, and they were entirely real—people threw stones at me on the street several times when they recognized me. One of the main complaints about me was that I portray real women. People would say, ‘These are our sisters, daughters, future mothers; you have disgraced them.’”

Alyon Saveleva, an artist from Ufa, was also subjected to harassment, which threatened to move from social media to “reality,” because she “portrayed various members of society, including sexual minorities, in the national costumes of Bashkiria.” In her words, all she wanted to show through the medium of art was that “My Bashkiri people are the same as all other peoples, and life here, as I thought, does not differ from the world community.” But the art only went so far before soil and destiny took over. Even though many viewers supported Saveleva, some were shocked by the portrayal of “the naked bodies of Bashkiri men and women,” and participants in the impassioned discussion (which included nationalist activists, members of the Public Chamber, representatives of political parties, and even the head of the republic) accused her not of “anatomy with pornography,” which was the case with Tsvetkova, but of “mockery of the Bashkiri culture,” since the anatomies of the men and women portrayed were covered with “elements of the national dress.” The audience was particularly sensitive to pictures of traditional fox hats.

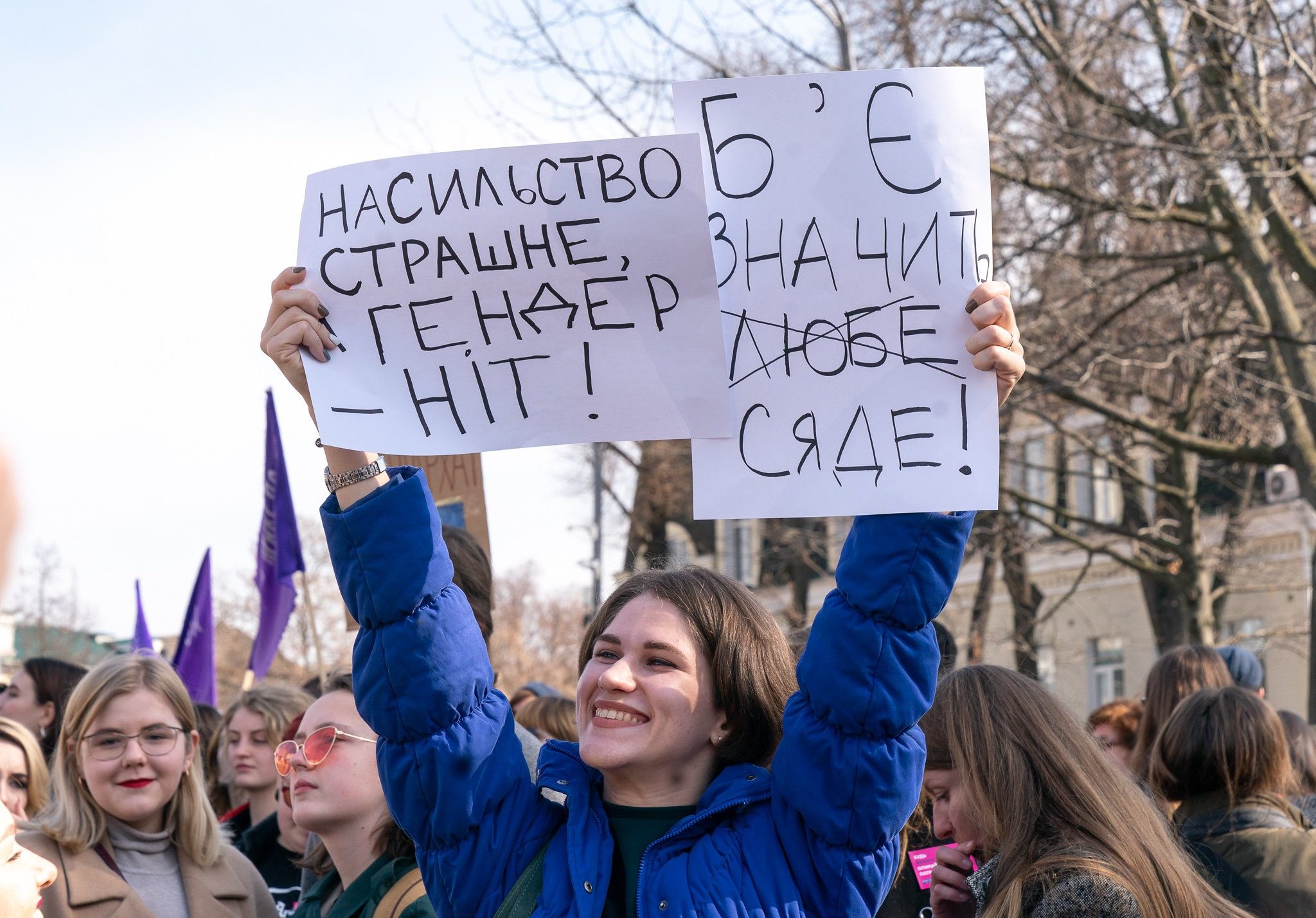

This story brings to mind another story that is also about hats and women. Last year’s March 8 women’s march in the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek was disrupted by the local version of the Russian Cossacks and SERBovtsy and Kyrk choro activists wearing ak-kalpaks (the national Kyrgyz head attire for men) after the police failed to act, or, more precisely, abetted. “I was walking there and saw stones flying at us, and these guys in ak-kalpaks running,” recounted artist Tatyana Zelenskaya, who participated in the march. She expressed her feeling—suffocation from injustice—in a bitter and expressive self-portrait where she is being led away by police officers and men in ak-kalpaks are destroying signs and attacking women in the background. Over 70 participants in the Bishkek march spent the worldwide flash mob to fight violence against women, which was held on the streets and in the squares of other countries on March 8, within the walls of a police precinct. The actions of people who aggressively oppose gender equality are taking a positive symbol of Kyrgyz culture and transforming it into a symbol of patriarchal violence and the suppression of women. The ak-kalpak’s national holiday, which was officially introduced under a 2016 resolution of the Kyrgyz parliament “to preserve the importance of the national headdress,” is celebrated on March 5, which makes it seem to counterpose women’s day in terms of time. This year it was held on Ala-too Square in Bishkek, while officials again failed to authorize the March 8 women’s march, citing the pandemic, which did not appear to interfere with the holiday of men’s national headdress.

In 2018 ADC Memorial drew the attention of the UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination to how elements of national dress are zealously bestowed with holiness and sometimes even forced on people (in particular, in 2018 the Kyrgyz parliament submitted the draft law “On Assigning the National Headdress Ak-kalpak the Status of a Cultural Symbol” for public debate. This draft law included clauses such as “The procedure for wearing an al-kalpak shall be determined by the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic” and “An ak-kalpak cannot be used for anything other than its designated purpose.” The law also proposed that male civil servants would be required to wear it and stipulated liability for “desecration” of the al-kalpak). At the same time, national dress is already popular in Kyrgyzstan—many people wear it with pleasure and at their own will, and human rights defenders have reported cases where it has been imposed and rejected (for example, in Osh Oblast, where a large percentage of the population is comprised of Uzbeks, the regional leadership forced schoolteachers to wear clothing with national Kyrgyz elements during work hours).

The “male state,” as represented by the eponymous group of women-haters and by other natural and legal persons, feels the full support of the state, and sometimes it seems that it acts at the orders of and certainly with the silent agreement of the latter, as was the case with the March 8 march in Bishkek or the threat against the female artist and activist Darya Serenko, who launched a “Day of Solidarity” with Yulia Navalnaya and female political prisoners during the recent protests.

Many of our female contemporaries are forced to live in the suffocating circumstances of the “male state.” Regardless of what side of the Caucasian or Ural ridge we’re on, this is our shared reality—when the police respond to domestic violence and promise to come only “when there’s a corpse,” when television programs transmit the embodiment of traditional values in the form of the forced marriage of a schoolgirl, when mothers are not allowed to raise their children: “Once upon a time, I don’t know in what century, a shepherd in a sheepskin hat who had sent his sheep to graze, sat down beside the fire and started coming up with fantastic stories, traditions, adats, where the woman is essentially not a person. Women aren’t worth anything here in Chechnya. Women have many rights under Islam, but actually for us, for the Nakh peoples, for Chechens and the Ingush, women are purely incubators, cleaners, servants, and nothing more. So you come into a family, you bear children, but these are not your children. They belong to the last name.”

“Your body is a battleground”—this is the oft-cited yet timely slogan of a Barbara Kruger silkscreen (1989), and this is far from a theoretical battleground—for the right of women to life, to liberty, and to art.

Olga Abramenko

Feedback

Feedback