In late June, at the height of the war, Ukraine ratified the Istanbul Convention – the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. On the one hand, this makes complete sense: Ukraine hopes to join the EU, especially in the current circumstances of war, and the Convention is one of the fundamental components of “European values.” But, on the other hand, ratification at this specific time also symbolizes recognition of the role of women at this most difficult moment for the country and respect for their equal rights. Even the stipulation that accession to the Convention will not result in changes to the Constitution or laws on the family, marriage, and child-rearing does not alter the situation: An important step has been taken, and there is no doubt that not just the EU, but, most essentially, Ukrainian civil society will monitor implementation of the obligations the state has undertaken.

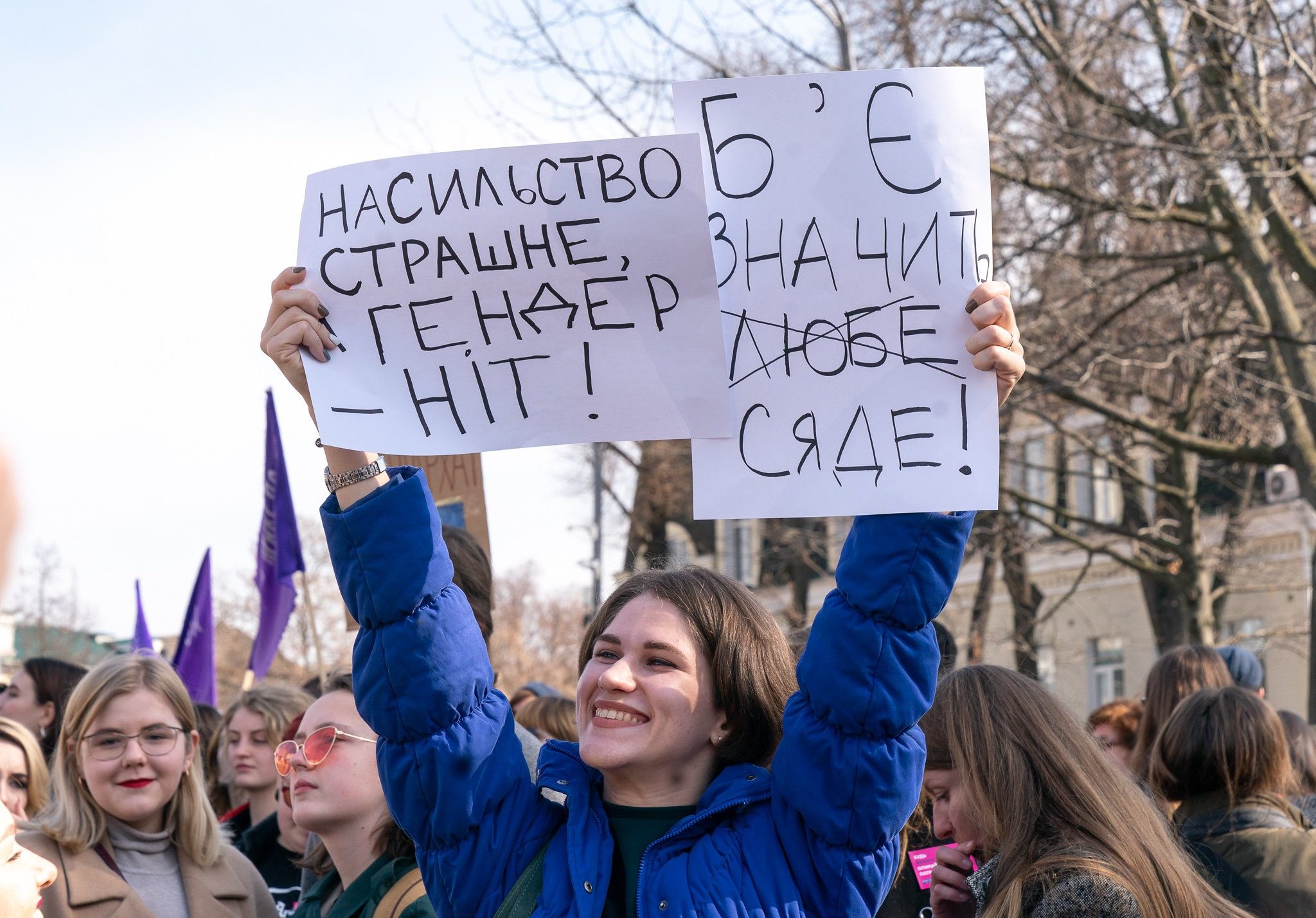

Photo credit: UN Women/Volodymyr Shuvayev (CC BY-NC 2.0)

It cannot be said that the ratification of the Istanbul Convention was easy: It has been over 10 years since Ukraine signed the Convention (2011), which was opposed by conservatives and religious figures, who traditionally fear the concept of gender and even the very word itself, which they often conflate with what they see as the disagreeable topic of LGBTI+ issues. However, there’s more: In early August, President Zelensky instructed the Cabinet of Ministers to consider the question of legalizing LGBTI+ marriages, having responded to the corresponding petition in the following manner: “Every citizen is an integral part of civil society, and all the rights and freedoms enshrined in Ukraine’s Constitution apply to them. All people are free and equal in dignity and in rights.” Since Ukraine’s Constitution interprets marriage as a union between a man and a women, and the Constitution cannot be changed in wartime, a solution could be to legalize same-sex partnerships, and experts see the creation of this institution as entirely plausible. Recognizing the equality of LGBTI+ people specifically during wartime is also symbolic as an appraisal of their contribution to the overall fight against Russian aggression. The petition says: “Today every day could be our last. Let people of the same gender have the opportunity to create a family and receive an official document confirming this. They need the same rights that traditional couples have.”

A study by the Center for Expertise in the Social Sciences at the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Sociology about the Ukrainian population’s tolerance for LGBTI+ people that was done on the eve of the war showed that support for the right of same-sex couples to register their family relationship has doubled since 2013. Twenty-seven percent were fully in favor, while another 26 percent were in favor with some stipulations (a total of 53%). This figure stood at 33% in 2013. Support for equal rights for LGBTI+ people is also growing, although unevenly in terms of geography, and society is still quite paralyzed in this sense. So the mythologized fears of “gender” are gradually receding.

Conservative elites in other former Soviet countries also fear the word “gender” and, even more so, the abbreviation SOGI (sexual orientation and gender identity). When reviewing state reports, various UN committees regularly issue “routine” recommendations like adopting a comprehensive anti-discrimination law and a gender equality law to countries that have yet to adopt such laws (if they have adopted such laws, the laws avoid the word “gender” and talk about equality between men and women). The “routine” responses are that other laws (generally the Constitution, the Labor Code, education laws, etc.) contain anti-discrimination provisions that are sufficient. Human rights defenders and UN committees insist that SOGI be included in the definition of discrimination along with a number of other attributes (skin color, ethnicity, beliefs, and so forth), but lawmakers are resistant to this and say that the attributes listed are more than enough and that SOGI is implied under “and others.”

However, the adoption of an anti-discrimination law, even an imperfect one, is already a major step forward: Such a law clearly articulates a ban on discrimination and liability for breaking it and creates a special body authorized to review complaints and perform expert evaluations. In late June, Tajikistan suddenly announced that the “Law on Equality and Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination” had been adopted by the lower house of parliament and was expected to be approved by the upper house; this was a surprise because, until recently, the government didn’t see any need for such a law. Even though SOGI was predictably not included as a ground for discrimination, the law still refers to direct and indirect discrimination, segregation, sexual harassment, victimization, and positive measures for fighting discrimination, using a contemporary approach and terminology.

The fact that the law was adopted does not really mesh with the overall impression of an authoritarian Tajikistan. However, this gesture shows that the country’s government is not indifferent to the opinion of the global community: The law was developed as part of the National Action Plan for 2017-2020 to implement the recommendations of states on the UN Human Rights Council. This was already the second cycle of review of the human rights situation in Tajikistan as part of the Universal Periodic Review. Now the third cycle is underway, and Tajik and international human rights organizations have submitted new reports: In particular, these reports raise the topic of discrimination against ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities. The recent events in Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast showed that the country’s government is heightening persecution of the Pamiri population. It would be nice to believe that the new law could create a platform for dialogue in the GBAO, which the Tajik government has basically rejected in favor of open repressions.

Tajikistan’s anti-discrimination law creates a legal framework for the fight for equality of other vulnerable groups, including “invisible” groups lumped under “and others.” Within this legal framework, transgender people who have been denied the ability to change their documents, HIV-positive persons who have been stigmatized, and victims of gender-based violence can file discrimination lawsuits.

Analogies are frequently made between the military aggression of Russia, whose government does not recognize Ukraine’s right to freedom and independent development, and the behavior of a domestic tyrant, who suppresses and terrorizes the people close to him. In fact, the ideological foundation of war is a tangle of imperial complexes, patriarchal “fastenings,” rejection of the rights and equality of others, and a pathological fear of “gender” – its main component. Support for equal rights for LGBTI+ people will most likely grow, including among people who oppose them, because of Russia’s clear menacing role in unleashing a war.

Russia is experiencing the triumph of obscurantism as other countries are making “gender” breakthroughs in the law. The fate of the domestic violence law, which has not been adopted for many years, is, sadly, well-known – what kind of Istanbul Convention can there be with that? And then they want to toughen the law on gay propaganda to include a total ban on this topic in public. Over the past two years, all the leading LGBTI+ organizations have ended up on the list of “foreign agents.” Then individuals started being added to the list: The Ministry of Justice is not concealing the fact that this law is being applied for discussing the topic of SOGI before a wide audience, as in the case of Karen Shainyan, who is challenging her status as a “foreign agent.” Russia has no intention of complying with the European Court’s judgment in the NGO “foreign agents” case.

Olga Abramenko

expert, Anti-Discrimination Centre Memorial

Feedback

Feedback