The new list of banned professions for women lifts restrictions in transportation and other spheres, but leaves over 320 of the 456 bans on the existing list in place.

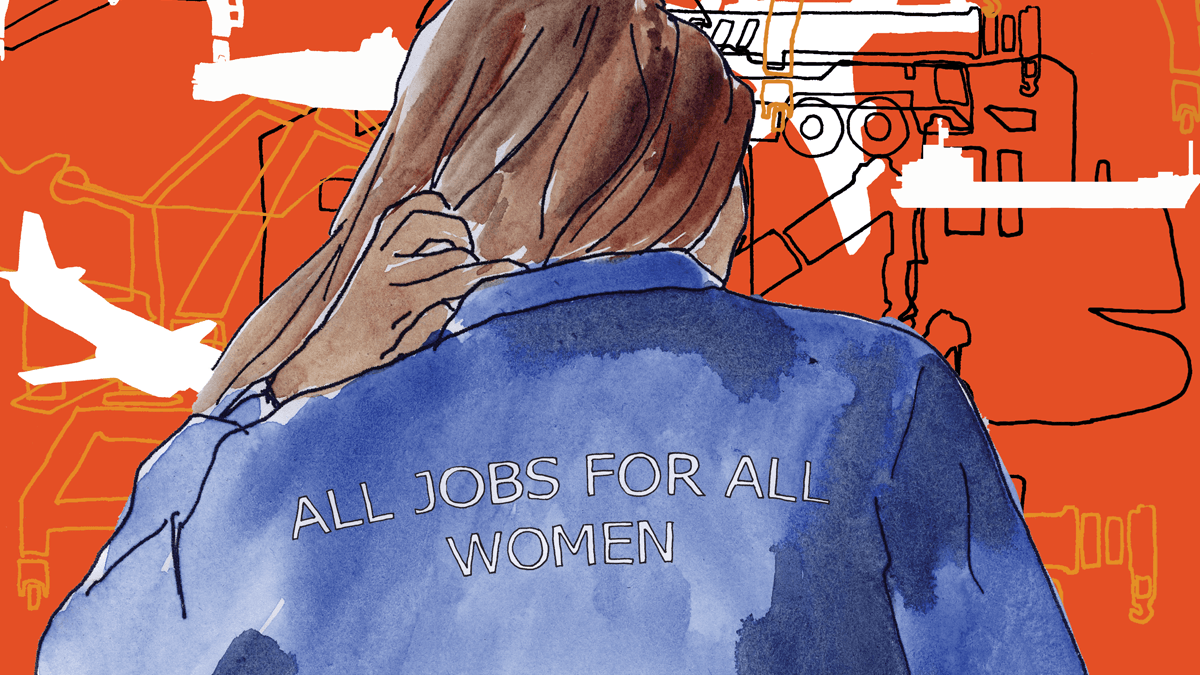

ADC Memorial and the campaign #allJobs4AllWomen welcome the first successes for Russian women who have triumphed in the fight to have bans on their chosen professions revoked. A draft of a new list of banned professions was registered by the Ministry of Justice on August 14, 2019—one-and-a-half years after work was started on it.

Employment restrictions for women will be removed from over 100 jobs when the new list finally takes effect. The majority of the heroines of #allJobs4AllWomen who openly spoke out against the bans on the campaign’s website can now officially work in their chosen professions as truck drivers, machinists and sailors on ships, and print workers. The fight waged by these claimants has opened up the transportation sphere to women.

This sphere includes many good job opportunities on sea and inland water vessels, the railways, and the metro, as well as is civil aviation.

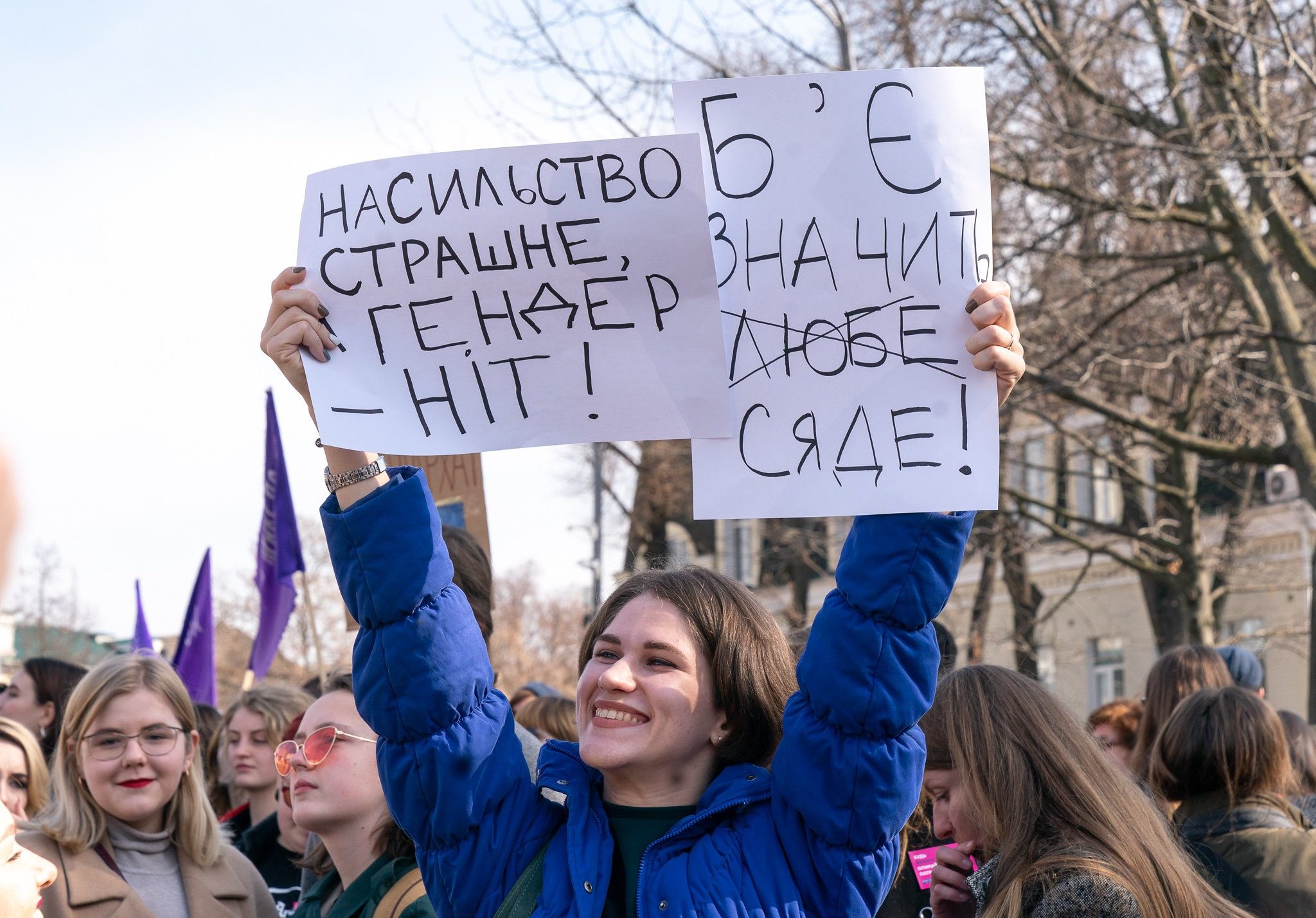

Reviews of the case of Svetlana Medvedeva, a navigation officer, in Russian courts and by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women ended with an RF Supreme Court judgment finding the ban on the employment of women on river vessels discriminatory and the Samara District Court’s de facto recognition that Russian norms do not correspond to international standards for equality and non-discrimination in employment. In November 2017, female workers in banned professions (passenger, freight, and water transport, print shops, and small businesses) addressed an open letter to Russia’s human rights ombudsman T.N. Moskalkovaya appealing for protection of their labor rights. In 2018, Russian Railways, the largest railway transportation company in Russia, came out in favor of allowing women to work in this industry. In addition to the applicants, commercial organizations, and NGOs, Russia’s professional union of sailors also voiced its support for cancellation of the ban.

Dozens of jobs will be accessible to women as a result of these changes. These jobs include machine operation work, some metalwork, construction, installation, and renovation jobs, geological surveying and topographic-geodesic work, processing of a number of chemical substances (rubber compounds, oil, gas, shale, and coal), tire production, maintenance, and repair, jute and hemp production, the manufacturing of musical instruments, and work in a number of areas of the food industry (fish harvesting and processing, baking, tobacco and fermentation, the perfume and cosmetics industry, and the mining and processing of salt). Cancellation of the ban on jobs at heights will allow women to work as parachutists and to repair power stations and networks. But women will have to wait for official employment in previously banned professions: this bill has not been able to reach the final stage of official publication for two years in a row. The current draft, which was written in July 2019, is the fourth version of the new list of banned professions. There were initially plans to replace the old list within six months from the day of the approved draft’s publication, but by the winter of 2019, there were already proposals to change the effective date to January 1, 2020. Under the most recent version, the list will only enter into force on January 1, 2021.

The profession of firefighter is officially banned for women, but this does not mean that women in Russia do not put out fires. They do, but they are not paid a fair wage and are not insured against the risks inherent in this profession. The situation is similar for porters—just because this job is on the list of banned professions does not mean women do not have to move heavy objects as part of their jobs. At the same time, they do not receive the compensation required for these risks. For women living in company towns connected with various areas of heavy industry, dividing professions into “female” and “male” leaves women without decent wages, since only various low-paying specializations remain open to them in these towns. And this is on top of the fact that many of them also provide for their children.

Anastasiya Dmitrievna Kosheleva

of the summary of proposals resulting from the posting of the draft on the preparation of a standard-setting instrument

In reality, the revocation of these bans is not enough to allow women to occupy previously inaccessible professions; in addition, actual conditions must be created for them to be hired for vacancies, and special temporary measures like the ones recommended by UN CEDAW must be adopted. These measures would include notifying employers and potential workers that women are now eligible for positions like metro operator and bus driver that have been banned to them for decades. For example, ads for vacancies for both positions have stated that only men are eligible, so it is important to notify women about the possibility of training and working in these specializations using all possible means (media, employers’ websites, unions, employment services).

Even though the new list has not yet entered into force, work must be started now to change the rules for accepting women into academic institutions for training in previously closed professions (including machinists, assistant engineers, bus and truck drivers, ship mechanics and motorists, sailors, and others) so that they can actually start working in these positions in 2021.

Broken promises” and “a long process for not much change”

Registration of the new draft of the list of banned professions with the Ministry of Justice is, without a doubt, a victory for the applicants who were fighting for their rights, but this document still has a number of shortcomings. According to information published by journalists, the list proposes restricting the labor of women in 98 jobs and positions, but, upon closer inspection, it turns out that many of the items on the list include dozens of professions from the old list.

In fact, the new draft contains 263 industries, jobs, and positions instead of the under 100 touted and bans women from over 320 professions of the 456 banned professions on the current list.

While trumpeting the reduction in bans, the authorities have worked zealously to retain as many restrictions as possible, as if they want not just to delay the new list’s adoption, but also to hide the final version from citizens critical of this discriminatory document. It’s no accident that the latest version of the list has still has not been published on the website of the federal regulations portal, which reflects the process of the draft’s adoption, and that the available text of the list sent to the Ministry of Justice does not correspond to the latest version of the Ministry of Labor order.

This list is too general and has not been worked through. Certain positions raise questions in principle. Like item 8 “Firefighting.” Why? How can this work impact a woman’s reproductive health? Does this mean it is not harmful to a man’s reproductive health? All the lists of banned professions should be revoked. The government should be working exclusively on occupational health and safety. Every position, every profession should be accessible and safe and should not present any great risk to workers’ health.

Anna Yevgenyevna Tartakovskaya

of the summary of proposals resulting from the posting of the draft on the preparation of a standard-setting instrument

The draft of the new list has repeatedly changed form: it initially listed 156 first and second hazard classes of chemicals that, if present at the workplace, prevented women from working there, but sweeping criticism of the obligation to determine the impact of these substances and the high likelihood of inconsistencies resulted in changes to this section. Curiously, the first version used the wording “chemical substances harmful to a person’s reproductive health,” which was replaced with “a woman’s health” in all subsequent versions, while the list of substances itself provided in one of the draft’s subsequent versions was not changed at all.

After an expert review of the draft, lawmakers decided to replace the inconvenient proposed list of the first and second hazard classes of chemicals with a list of chemical productions banned for women. But while the existing document lists specific positions like “workers, shift leaders, and specialists working with boilers and in the hand-crushing/processing stages” during the production of certain products, the new draft proposes banning women from all production in general and from using 23 organic and inorganic chemicals.

Men also have reproductive health, and there are also infertile people and people above child-bearing age who have not retired. If work conditions at a company affect the reproductive health of workers, the government should improve conditions instead of depriving half of the country’s working population, which includes a tremendous number of single mothers doomed to eke out a living due to lack of jobs, of the chance to earn a living.

Maksim Volgin

of the summary of proposals resulting from the posting of the draft on the preparation of a standard-setting instrument

The July version of the list has a structure similar to the existing Resolution and proposes reducing the number of sections from 39 to 21. Even so, the document’s final version was not its shortest. The draft of the list published in February 2019 contained the least number of banned professions: it consisted of only 28 items, not including sections, four of which contained ambiguous restrictions connected with the impact of chemical factors, vibration, ionizing radiation, and cooling or warming microclimates. However, most of the remaining bans (20 of 28) are contained in only one section of the new draft.

The content of the proposed list also raises questions: a small number of jobs ban the labor of women only if they are performed manually (unlike the full ban in the current Resolution). These include pitch grinding and loading and unloading work at ports; other professions like spinning lathe operator are banned even if they are mechanized. New bans have been added to the list like wing technician. A number of jobs in the textile and light industries are duplicated in the new draft (sections 68, 69, 70, and 71). It is sometimes difficult to explain the appearance or disappearance of certain bans, while the legislature has not found it necessary to justify the significant differences between the drafts submitted over the past year-and-a-half.

Purported concern for women’s health

Following the fundamental principle of a ban on discrimination (which was cited by participants in the public debate), the legislature dropped its proposal to restrict the list to women aged 18 to 49. Unfortunately, the state continues to maintain that the document itself does not restrict rights and to amend the list instead of admitting that it is simply irrelevant and that this form of concern about a woman’s health amounts to unjustified interference in women’s lives that conflicts with their freedom of choice and the right to self-realization. During public debate, a female representative of Lukoil proposed a more economically favorable and effective way of solving the problems of violation of the principle of equality in employment, restrictions on women’s labor in a number of professions, and staffing shortages by using the concepts of “access with informed consent,” “when a women may be allowed to work in harmful conditions if she provides confirmation, in writing,” that she understands the risks to her health.

I’m child-free, and I believe that I have the full right to manage my life: to choose my profession in accordance with my wishes and not with someone’s instructions. And let’s not even mention that many women are shut out of high-paying professions in light of their “danger.” A large number of children are raised by single women, but these women don’t have the right to get a job that would allow them to feed and successfully raise their children, while arduous and low-paid jobs like cleaners are open to them. This doesn’t look anything like concern.

Alena Kraeva

of the summary of proposals resulting from the posting of the draft on the preparation of a standard-setting instrument

Unfortunately, the legislature has yet to consider this form of consent, so female rescuers still cannot officially work as firefighters or divers, despite their professionalism and calling.

The realization of rights in today’s conditions requires an active position. ADC Memorial calls on women who want to find employment and receive training in their desired professions to send statements to academic institutions about opening admission to women and intends to support applicants who achieve open access to banned professions.

Inessa SAKHNO

Feedback

Feedback